Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Evolution and Stories in Political Science

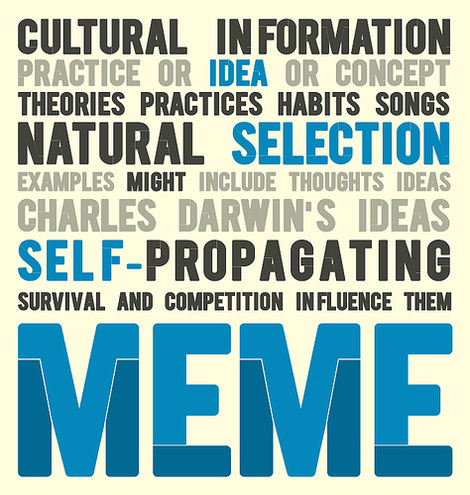

In our class The Story of Evolution and the Evolution of Stories, we have been reading Daniel Dennett’s Darwin’s Dangerous Idea. In the book, he discusses the idea of memes, units of measuring culture, inspired by the idea of genes. Memes to me are difficult to explain, because they are so general. Can culture really be measured? We only discovered DNA in the past century, and still cannot come close to describing the many functions they perform. We cannot fully explain the cell, so we cannot fully explain the brain, so then how can wee fully explain culture which is even more complex?

Culture cannot be broken down in such an arbitrary way. The abstract cannot be condensed into a solid. A large and complex process or phenomenon cannot be broken into pieces so simply. In an attempt to cover everything into one category or theory, we run the risk of over-generalization and over-simplification. This takes away from the real issue, and can prevent those who wish to study an issue in greater depth from doing so.

I have run into this problem not only in Dennett, but also in another class on international politics. We were discussing different theories on international relations and politics and the political process. I found that many of the different theories I encountered were also quite general, and I felt that really diminished the complexity of the the global system.

One does not need telling that the world is comprised of thousands of diverse and dynamic cultures and subcultures. Each country is a little different, each region is even more distinguishable from the other. A theory that may explain one region, may fall short in another. There are an infinite number of variables that can affect a country’s development. Even if one could predict all the human effects on a country, not taking into account human evolution and development, one could not predict climate or random accidents or outside countries’ influences. One country may be strong because they were very technologically advanced in weaponry, another could be very skilled in economics, and still another may have simply chanced upon a very rich ecology capable of supporting their population. There are just as many ways for a country to falter and fail, and those ways have more than just one cause.

In Europe, as people became more and more drawn to the study of politics, a predominant theory was Realism, or the idea that civilization and international politics are driven by war. Human nature, according to this theory, is naturally predisposed to violence and in order to have peace, a country must prepare for war. Naturally today many political scientists reject this theory for obvious reasons. It completely overgeneralizes, and if anything, says more about the political philosophies governments of the time used to act, rather than the forces acting upon them. Other theories acknowledge that this theory is too over-simplistic, but often can be over-simplistic on their own.

Take institutionalism as an example.

Many theories focus on smaller influences, for example feminism. Feminist political theorists argue that women have had a substantial influence on politics despite not being in inherent positions of power for the majority of history. Women being in a supportive role, according to the theory, in fact allowed for more political success. This, for example, includes women who served as nurses and provided more intimate services, so to speak, to soldiers allowed them to relax and prepare better mentally for battle, an across the board traumatic experience. This theory has valid points, but obviously cannot explain everything that happens in the world.

This is acceptable. By first understanding smaller sections of the political process, we can then understand the process as a whole. Right now we are not close to understanding the over-arching system, but we do have some idea of different parts of it. War, territory, economy, environment, gender, population, ethnicity, culture: these are only a few concepts that are part of the greater concept that is politics.

Having one theory also prevents space for change. Politics are constantly changing and evolving. As a classmate wrote in his blog post, perhaps politics can also be evolutionary. We have seen many political structures come and go, and what works one time does not work another. That is when revolution happens.

Take the events now in the Middle East. This region was first ruled by empires and colonial powers, and when that rule no longer worked for the people, they overthrew it. Now, the governments that came in after have been overthrown, or are in the process of great upheaval. Like an organism trying to make its ecosystem, these countries are trying to make it within their own, larger worlds.

John Baylis and Steve Smith, The Globalization of World Politics. 4th Edition, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2008.

Karen Mingst and Jack Snyder (eds.) Essential Readings in World Politics, Norton, New York 2004.

cr88, "Evolution and Revolution". Serendip: /exchange/node/9304

Comments

"Complexity and Causation"

alexandrakg --

since Paul and I have set up this course as a "two-cultures" dialogue between science and the humanities, it's a particular pleasure to get some student work in the social sciences. We have lots of conversations in class about the use-value of evolutionary theory for literary studies, and vice versa, but not much discussion about the use-value of both of these sets of ideas for political science and history--which is where your work so usefully enters the picture.

I hear you saying here that you have a parallel problem with reductionism in evolutionary and political theory: in both fields, complex systems are reduced to small parts, abstracted into general patterns that only vaguely reflect the whole. And it is not @ all, or often, the case, as you observe, that "by first understanding smaller sections of the political process, we can then understand the process as a whole"; ofttimes the whole is much greater than the sum of the parts; ofttimes it is the unpredictable outcome of the interaction of many small parts.

A few years ago, I co-edited a special volume of essays on emergence theory, including an excellent one by Tim Burke, a colleague in the History Department @ Swarthmore. It was called "Complexity and Causation," and in it Tim laid out a very striking description of the way that historians find themselves caught between arguments that "operate at long scales of time, refer to underlying structures or forces, and are relatively deterministic in nature" and those that "tend towards short scales of time, refer to specific and granular events or episodes, and often stress the relatively contingent or unintended nature of causality."

He then turned to emergence as a way of thinking about causality that "is centrally concerned with processes ... in which complex structures arise from simpler and more inchoate practices. If one thinks about imperial administrators, African elites, peasants, white farmers and other discrete groups of agents in early colonial Africa as having 'rulesets' that shaped their actions" (for example; this is Tim's area of study) "it is quite possible to see how the simultaneous interactions of their differing priorities could converge into a large-scale system without any of the actors necessarily intending to create that system."

Now that's a story that-- by looking @ "the massive simultaneity of agents acting independently of one another within a constrained environment or space"-- gets from different parts to the system as a whole, in way that makes sense of causality.

As Tim observes in his essay, "Some kind of reductionism is an intellectual and rhetorical requirement. Emergence attractively envisions that relationship as between one relatively simple state of affairs and a consequently more complex one: it gets to have its reductionist cake, but eat it too, to pose a dynamic causal relationship between simplicity and complexity, agency and structure."

Does that address your concerns? Do you find it a useful story?