Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

On the Argument of the Origin

Title: On the Argument of the Origin by Ewashburn and Ckosarek

Purpose: To evaluate the relative merits of two styles of argumentation in Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and discuss their relevance to a modern audience.

Materials: On the Origin of Species, Laptops, Brains

Hypothesis: The more linear argumentative style and the concise information presented in Chapter 9 would be more accessible to modern-day audiences because it reflects a modern style of argumentation.

Procedure:

1. Evaluate Chapter 4 and Chapter 9 for their construction and content.

2. Exchange write-ups and respond to them.

3. Come together and evaluate all of the written materials.

4. Re-evaluate the relevance of each chapter in light of the evidence that was presented throughout the procedure.

Data:

|

Ewashburn: For many modern students, including myself, Darwin’s On the Origin of Species is, frankly, a slog. The first half of the book, in which Darwin introduces his theory of evolution, lists various case files of organisms’ development and variability, reiterates the previous findings of other scientists ad nauseam, and generally stuffs itself full of pigeons and pairings in order to reach what is nowadays a foregone conclusion. As much as his cautious, meticulous categorizing of data is to be admired, Darwin’s style leaves me cold, and his surfeit of examples ultimately preaches to this choir of one. However, in Chapter Nine, this text loses its tediousness and becomes more relatable and relevant to me, as a modern student. In it, Darwin anticipates a criticism of his theory, and, instead of hiding behind other people’s work to protect his claim, uses source material as a supplement to highlight and promote his theory. This argument is not only a refreshing change of pace from the endless empirical inventory, but is also more pertinent to a modern audience, both in its content and its style. Chapter Nine deals with the geological flaw in Darwin’s theory: “… the number of intermediate varieties [of organisms], which have formerly existed on earth, must be truly enormous. Why then is not every geological formation and every stratum full of such intermediate links?” (Darwin, pg 269) The argument is a compelling one; if organisms have changed over time, then surely there should be some physical examples of those transitional forms. Why is it, then, that so few of these transitional forms exist today? Although Darwin does explain why he believes there is no geological evidence to support his theory, the question itself is just as relevant to a modern audience than the issues and evidence discussed in any of the preceding eight chapters. In a culture inundated with the concept of evolution, most modern readers would go into reading On the Origin of Species already assuming that his theory was the most plausible. But those students would also have the opportunity to ponder the theory’s flaws themselves, and many would come up with the same question as Darwin supposed his critics would. Unlike the theory itself, however, such flaws are rarely taught in a school curriculum—indeed, the theory of evolution is rarely ever taught in its entirety—and thus a modern reader might not be able to fully understand the theory of evolution. So when Darwin answers his imaginary critics, he is also answering the questions of a modern audience, questions arrived at independently, but are no less relevant than they were in the 19th century. Instead of discussing what many readers today find to be a foregone conclusion, Darwin presents us with a fresh take on his theory, and, though this Just as the content in Chapter Nine is more relevant to a modern audience, so is the style in which that content is presented. As students, we are encouraged to use the resources available to us to foment and supplement our own ideas, as opposed to using the findings of others as a crutch leaned on to reiterate a conclusion others have already reached. For the first eight chapters, Darwin writes in the latter style. I understand that the introduction of such a radical theory required the endless examples in order to prove the theory’s veracity; I understand that the mention of other scientists’ names in conjunction with the evidence cited in support of this theory lent the argument credibility. Still, for all that this argumentative style was relevant in its time, it is nevertheless an exercise in tedium now. However, Darwin writes Chapter Nine as himself, not as another scientist, and uses his findings and the findings of others to support his argument, not to hide behind so as not to be eviscerated by critics. In this excerpt, Darwin uses his knowledge to discuss the poorness of our geological record due to the fluctuations in sediment levels: “I am convinced that all our ancient formations, which are rich in fossils, have thus been formed during subsidence…. All geological facts tell us plainly that each area has undergone numerous slow oscillations of level. Consequently formations rich in fossils and sufficiently thick… to resist subsequent degradation, may have been formed… during a period of subsidence, but only where the supply of sediment was sufficient enough to… embed and preserve the remains before they had time to decay…. Thus the geological record will almost necessarily be rendered intermittent. I feel much confidence in the truth of these views, for they are in strict accordance with the general principles inculcated by Sir C. Lyle” (Darwin, pg 276-277). We can see that Darwin uses his own knowledge to state and buoy his argument, only using the findings of Sir Charles Lyell as a supplement in the end. Even then, he mentions this congruity with others’ findings succinctly, instead of babbling ad nauseam about others’ findings until he thinks his reader is ready to believe him. This is the style of argument we are taught in school, and its prominent use in this chapter makes Chapter Nine the more relevant for a modern audience. As much as I value and respect Darwin for all that he contributed to modern science, his text, as it stands, is excruciating. Its endless lists and citations make the process of reading a grind, and its less-than-linear argumentative structure, coupled with our advanced knowledge of the theory of evolution, turns this modern reader off almost entirely. In Chapter Nine, Darwin displays a defense against his theory’s flaws and an argumentative style that were not only well before his time, but remain relevant even in our modern age.

|

Ckosarek: Darwin’s The Origin of Species was first published in 1859, at the height of the Victorian Era in Great Britain. At the beginning of Queen Victoria’s reign, the morality of British citizens was intertwined with their religious and social upbringing; members of all social classes read the Bible and were expected to follow its advice literally. Children’s games and books focused on religious morality as a way of life, and scientific naturalism, which then asserted that God had agency in the development of the world, was the reigning method of scientific inquiry. As Victoria’s reign moved toward the 1850s, however, the idea that religion, God’s control over life, and scientific inquiry coexisted harmoniously began to shift, most notably with Darwin’s publication (but also with scientists around Darwin’s time, like Lamarck, who asserted that there existed heritable characteristics in animals, and Robert Chambers, who published Vestiges, a book which argued for the development or progress of nature). When Darwin published his volume, British society was hanging between religious fervor and scientific empiricism, which, though it first appeared in the Enlightenment, gained more credibility as the Industrial Revolution deepened. In order to challenge the long-standing belief that “God did it” (whatever “it” happened to be), Darwin had to prove his case with scientific research that left no room for plausible religious argument. To do so, he backed his theory with examples – lots of examples –, which brings me to Chapter Four of Origin, entitled, “Natural Selection; Or the Survival of the Fittest.” Darwin draws first on the science that the British population already accepts, specifically alluding to Galileo’s heliocentric view of the universe as evidence that “Nature . . . [is the] product of many natural laws” (Darwin 78). If the British accepts that the stars can be governed by the natural law of gravity, who would argue that life, too, is not governed by similar laws? But Darwin does not simply stick with this logic to support his theory of natural selection. Logic does not have the empiricism needed to sell an idea to the hesitant and still religious British people. So Darwin extends his evolutionary argument with his observations and research. He describes the wolves of the Catskill Mountains, insects visiting pollinating flowers, and the “233 seedling cabbages from some plants of different varieties growing near each other” (95) that he raised and observed himself. But not only does he use his own examples, like any good scientist, Darwin draws on the research of others to support his findings. While talking about the variety found in the same species of “guillemots in the Faroe Islands” (88), Darwin cites Graba for his research efforts. At a later point, he extends the argument of “Sprengel, Knight, and Kölreuter” (92). Interspersed with these examples is his furthering of his assertion that there is no more logical way for the world to be changing in the ways that he has recorded. To extend his own argument, Darwin globalizes his observations, thus transferring them from scattered observation to truth by linking them with a common theory, as shown in the following: . . . yet that the course of modification will generally have been more rapid on large areas; and what is more important, that the new forms produces on large areas, which already have been victorious over many competitors, will be those that will spread most widely, and will give rise to the greatest number of new varieties and species” (101). The modern reader might argue that Darwin’s incessant drilling of his theory into the minds of his readers through countless tedious examples shows evidence of poor tact in his argument. Given the social climate in which Origin was published, though, it is the case that not only were chapters such as chapter 4 (which I have chosen to highlight) supportive of his argument, but they were actually what moved his readers from their religious conviction that “God did it” to believing that there were natural forces (like the force of gravity in which they already believed) driving the species of the world. Though Darwin certainly met with harsh clerical criticism, it would seem that his seemingly long-winded chapters are what highlighted the flaws in his opponents’ religious arguments against his claims. One of Darwin’s bitterest contenders, Reverend Adam Sedgwick, argued against Darwin from a philosophical point of view, stating that Darwin’s argument ignored “the moral and metaphysical part of nature.” But when it came to empirically proving just where the “moral and metaphysical” parts of nature explained the world in a more effective way than Darwin had, Sedgwick’s argument was at a loss. Because Darwin presented a volume of empirical evidence and was able to tie that evidence together with a uniform thread, his work was effective in persuading the minds of his time to accept his theories. Had his argument been brief or linear (namely, in the concise style favored presently), it would have risked its validity by creating an opportunity for more gaps in his logic, thus inviting stronger opposing arguments. Even though his verbosity is not a favored style of modernity, it is absolutely crucial that his longest chapters – like chapter 4 – be included in his text and be valued for their power of persuasion.

|

|

Interpretation:

|

|

|

Ckosarek’s response: Chapter 9 has more action. It’s more to-the-point. It’s more combative. I agree that modern audiences would most likely gravitate toward the style of writing presented in Chapter 9. After all, doesn’t that chapter value all of the same things about academic, argumentative prose as modern society? “Proper” American academic argument stipulates that writers make a claim, develop a thesis, rebut their naysayer, and land smoothly. Our preferred style is concise, using the least amount of words and examples necessary to get our point across. I would bet that if you gave a class of tenth graders a copy of Origin and asked them to pick out the best-organized chapter, they would bypass Chapter 4 and head straight for 9. In gravitating toward Chapter 9, however, I worry that we will lose the value of the longer-winded chapters. While 9 is useful to hook the modern audience, 4 was what probably hooked audiences of the past. Heaps of evidence and analysis is what first drew readers into Darwin’s argument and made gave Origin the credibility it needed to be passed through the ages so that we might engage with it today. Chapter 4 indirectly contextualizes and foregrounds Darwin’s rebuttal in Chapter 9. In a tangible way, 4 presents the evidence that will later support the claims of Chapter 9. In an intangible way, though, 4 also indicates how Darwin perceived his audience to think. He knew that he needed evidence – and a lot of it. He knew he needed to explain time upon time. That was how his audience was going to buy his story. If the modern audience values the merit of Chapter 9 as a scientific essay over that of Chapter 4, I would suggest that this same audience then read Chapter 4 not as a “science story,” but as an historical story. The appeal of Chapter 4 for today’s audience is perhaps found in its historical social implications than its construction and claim.

|

Ewashburn’s response: After reading Ckosarek’s defense of Chapter Four, I have to concede that I may have been a little too harsh on Darwin. Immersed as I am in the 21st century, and having been born and bred in the USA, I tend to forget the startling impact Darwin’s findings would have had on 19th-century British citizens. Every example that I find tedious now must have come as a revelation to Darwin’s original readers, each pigeon’s feather a layer being peeled away from that onion of the mystery of our origin. Of course Darwin would have needed all of those examples, and of course he would have had to defend himself using others’ findings. To do any less would have rendered his theory toothless, flaccid, utterly inconceivable. I was particularly struck by the way Cassie points out how Darwin manipulated the British people’s acceptance of Galileo’s heliocentric view of the universe to augment his argument. After being reminded of that allusion, it occurred to me that Darwin’s processionals of his findings may have been a way of softening the blow that was his argument: if he used examples that the British people would be familiar with, such as pigeon and dog breeding, then perhaps they would be more willing to accept his proposal as a way of explaining life as they knew it. Still, even though I may have been too harsh on Darwin, I still believe that the style and content of Chapter Nine are more directly relevant to a modern audience. Chapter Four grounds Darwin’s theory in historical context, and is certainly an invaluable text for anyone who wants to learn about the evolution of the eponymous theory. But Chapter Nine remains relevant and persuasive after over a century, even after we’ve learned so much more than Darwin knew. Cassie’s defense has made me appreciate Chapter Four more, but has not diminished my belief in Chapter Nine’s relevance.

|

Conclusion:

After evaluating our evaluations, it became clear that although one chapter would probably have greater appeal to modern audiences, both chapters are integral in not only understanding the story of evolution, but the development of the theory of evolution. Reading the text means not only understanding the scientific theory but its historical and social implications throughout time. Taking the text holistically, Darwin’s dual argumentative styles make this work timeless in that it was able to appeal to and persuade audiences of Darwin’s time, yet is still able to continue persuading modern audiences already familiar with his story.

Sources:

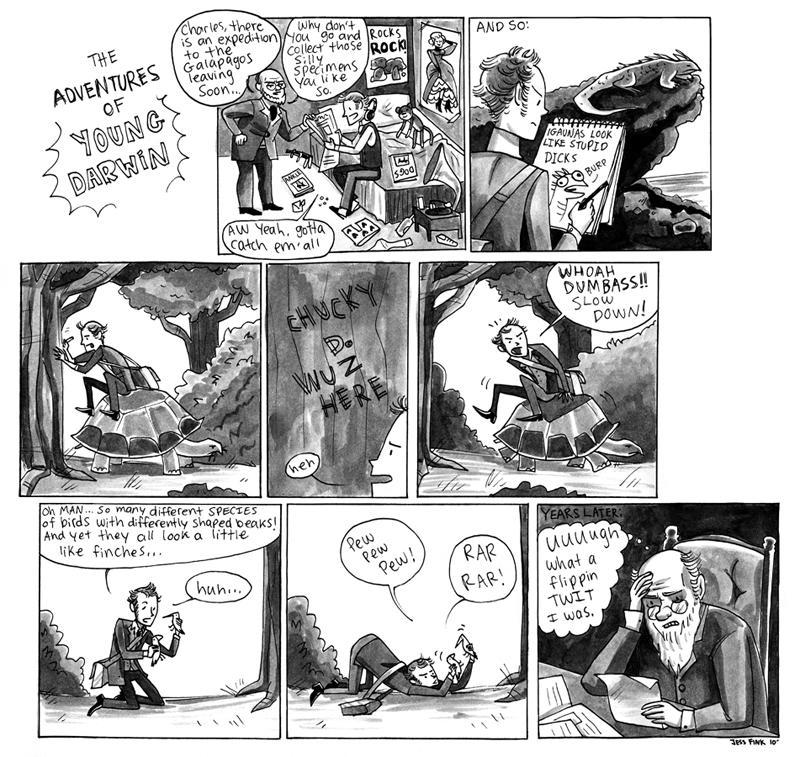

http://www.harkavagrant.com/history/YoungDarwin.jpg

Darwin, On the Origin of Species

http://www.bookwormlab.com/content/images/samples/essay_outline1.png

http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/sedgwick.html

http://www.hyperhistory.com/online_n2/people_n2/science_n2/images/heliocentric.jpg

http://www.lucidcafe.com/library/96feb/galileo.html

http://www.midthun.net/the.htm

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/modsbook10.html

http://www.marxists.org/glossary/terms/e/m.htm#empiricism

http://www.victorianweb.org/science/chambers.html

http://www.victorianweb.org/science/lamarck1.html

http://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI3260961/

http://www.clas.ufl.edu/users/snod/VicAgeTimeline.html

http://logicmgmt.com/1876/overview/religion.htm

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/08/science/08creationism.html?_r=2&scp=2&sq=evolution&st=cse

Comments

arguments, origins, evolution

"I want to invite readers to read our paper for the dual aspect of this webpaper that the titles imply"

And perhaps as an illustration of an evolutionary, co-constructive inquiry, approach to the interpretation of text, one in both the "orgin of the argument" and the "argument of the origin" derives from letting differences interact to generate new things, not only unconsciously but consciously as well?

"Frankly, a slog"

ewashburn, ckosarek--

much to delight in here, beginning w/ your twinned titles, continuing through the funny mixed metaphors ("each pigeon’s feather a layer being peeled away from that onion of the mystery of our origin") and arriving, finally, @ a fuller sense of how Darwin writes (and the effects of his writing on various audiences, in various eras) than either one of you might have produced on your own.

I'm tickled, of course, that you play w/ the format of a lab report, and intrigued by the way you follow conventional scientific practice in distinguish "data" from "interpretation" (though only by title? ewashburn's "data," for example, is filled w/ opinion--Darwin's text is "excruciating," reading it "a grind," etc. etc.) And I'm very glad to see you using the resources of the internet--the images, the active links, the columns of paired readings and responses (though we need to work on that formatting, I think; also there's a strange ellipsis in the center of ewashburn's column??).

A number of interesting things emerge along the way, and you raise a number of questions I'd be happy to have answers for. For starters, ckosarek: how do you understand the difference between a 'science' story and a 'historical' one? (What do you make of Paul's suggestion, when he laid out his templates for various sorts of stories, that a scientific one was always historical: a record of change with a time dimension?) In the comparison you all develop between "the concise style favored presently" and Darwin's more elaborate form of 19th century argumentation, I also see resonances w/ a conversation we're having in my other class, about "how we read" on the internet. Katherine Hayles argues for a disciplinary shift to a broader sense of reading, to include hyperreading--reader-directed, screen-based, computer-assisted reading, searching, filtering, skimming, hyperlinking, "pecking," fragmenting, juxtaposing, scanning, the strategy of reading in an "F" pattern....Check out that discussion if you want to think some more, not just about the evolution of prose style, but the forms of reading that have evolved along with it....

Not to mention the forms of writing! As you well know, ewashburn (but other readers may not) you are stepping here into a series of writing experiments that ckosarek began in Facing the Facts last semester, when the main fact she faced up was the limits of the argumentative pose that characterizes most academic work, and her main experiment (though ostensibly she was writing about copyright) was trying to get "beyond" that sort of positionality. So (whether you intended this or not), I read this joint paper as a further step in that process, and my main response has to do w/ nudging it even further along.

Here's what I see. You've set this up as a debate: RESOLVED: CHAPTER 4 IS MORE EFFECTIVE THAN CHAPTER 9. Each of you argues her position, to counter the other, with ewashburn situating hers within her own experience or reading--being "left cold" by Darwin's style--while ckosarek places her discussion in a historical context. That makes for a nice full reading through the ages (I balk @ overgeneralizing from your own experience to that of all "modern readers," and I balk, too, @ "timeless," but will buy 150 years and the testimony of a single modern reader!).

Along with several other colleagues, Paul and I have spent a lot of time working, in classrooms and faculty working groups and elsewhere, on open-ended forms of co-constructed dialogue; if you want to learn more about this process, you might check out On Dialogue, Culture and Organizational Learning. My own favorite part of this essay is the way it calls for "suspension"--not confronting a situation immediately (and so polarizing the discussion) but rather choosing to "suspend", letting our perceptions rest for a while to see what more will come up, both from ourselves and from others. Doing so creates a space for some real dialogue (as opposed to a debate, and the inevitable stand-off) to arise. That's the sort of conversation I'm nudging you towards, for the next round (there will be a next round, yes? I hope so!)

Our Titles

I just realized that Ewashburn and I have two titles for this piece - "On the Origin of the Argument" and "On the Argument of the Origin." I was going to point this out to her, but I think this dualism provides an interesting way of looking at our paper. In one sense, we're looking at the "origin" of the argument by examining its relevance in a changing societal context. And, more prominently, we're also looking at the way that Darwin's work is constructed (the literal "argument" of the origin). So instead of changing the titles, I want to invite readers to read our paper for the dual aspect of this webpaper that the titles imply.