Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

A Webbed Story: Manhua and Manga, Hong Kong and Japan

Frames can symbolize things (conclusions, formalities, endings, etc.)—boundaries that are hard to see. Frames can also be more like windows, allowing viewers to reach through them into worlds beyond. And frames can be less like frames and more curtains or webs, airy with their in-betweens, but still providing a gauzy boundary through which to view those worlds beyond. My framing web is this: a few strands of our class discussions got tangled, and here I am, looking at international comics.

The tug on the first thread came when Wai Chee Dimock came to speak with our class. While we read her paper on databases as genre, Introduction: Genres as Fields of Knowledge and discussed the meaning of the ‘science fiction’ genre label, our class also treaded lightly on the meaning of international literature. We touched on international works like Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, and The 1001 Arabian Nights, and were left to ask what genre really meant on an international scale (could it carry across culture? is genre just a generalization of culture?).

I pulled on the next thread while our class looked at a very exemplary graphic novel, Neil Gaiman’s A Game of You, which was beautifully crafted and ripe with purpose, but could not really answer the question of the international genre of comics –it was an American graphic novel by definition. Very academic and one of the best examples of comics as art, it was critically acknowledged to be above genre comics. Which left me wondering about how much of the comic is just form, and whether comics are just a medium of genre (not a genre themselves)? And so the two threads crossed, and I began asking myself how international was the genre (or medium) of comics.

Then even more threads began to come together, and I could almost see a image forming out of the tangled mass, a picture that looked tantalizingly like a final essay. We had read snippets of Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics through the class blog, and I borrowed a copy, hoping the work might help me frame my thoughts. About halfway through, McCloud mentions Japanese manga, and how it developed separately from American comics, just like Japanese film developed separately from Western film. I noticed that the same techniques and structures were used in Japanese comics as in Japanese films, and I began to wonder if the same was true about Hong Kong film-craft, which developed a very unique cinema reflective of its unique history. Would comics there be the same? So my web tightened its grip—I was caught. I began research on Japanese manga and Hong Kong manhua (translation: comics) as international genres and historical media.

As manga and manhua developed in their respective territories, their historical threads overlapped and revealed surprisingly similar international themes. In Japan and Hong Kong politics, censorship, the definition of respectable art, and the handicaps of technology all played roles in shaping the modern role of comics. But manga and manhua are still two different forms of the same genre. Each have their own separate histories and their own separate techniques that make them discretely manga or manhua. When stepping back and looking at the broader light shed by manga and manhua there are more than similarities and differences at stake if we want to ask ourselves how international comics are…

To start with, let’s be assured that manga and manhua are indeed comics (just as much as, say, American graphic novels are comics). Let’s take, for instance, Scott McCloud’s handy definition of comics: “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence” (McCloud 9). It can be safely stated that both manga and manhua fit into this broad definition, since they both use a combination of pictures and words to convey information or provoke a response in their readers.

It can be safely stated that both manga and manhua fit into this broad definition, since they both use a combination of pictures and words to convey information or provoke a response in their readers. So they are comics, but what distinguishes their threads from those of other comics? What frames these two genres or media --what curtain separates them from the rest of world-comics? They share devices with comics across the world, such as panels and word balloons, but they also have their own unique details, including their writing (kanji) and pacing. It is also clear that their respective historical developments helped give shape to their unique forms.

So they are comics, but what distinguishes their threads from those of other comics? What frames these two genres or media --what curtain separates them from the rest of world-comics? They share devices with comics across the world, such as panels and word balloons, but they also have their own unique details, including their writing (kanji) and pacing. It is also clear that their respective historical developments helped give shape to their unique forms.

Kanji is a pictorial, ideogramatic form of writing that both the Japanese and Chinese use as a writing system. The Japanese have other writing systems as well, but kanji, which they borrowed hundreds of years ago from mainland China, is one of the most important. In Japanese and Chinese the written kanji characters for ‘manhua’ and ‘manga’ are the same. In Japanese the first kanji is man (pronounced mahn) which translates to involuntarily, corrupt, or ‘in spite of oneself’ while the second kanji, ga, translates to 'picture'. The translation for 'manhua' is approximately the same, and it is said that the Chinese borrowed the characters for ‘manhua’ from the Japanese in the early 1900s (Wong 11). The term is said to have been coined by early 19th century print maker Hokusai Katsushika to describe the action, puzzle, cartoon, and horror pictures of the day (Schodt 35). Just like with American comics, there is a bias against comics as anything other than lowly popular entertainment in Hong Kong and Japan –even built into the name manga!

In Japanese the first kanji is man (pronounced mahn) which translates to involuntarily, corrupt, or ‘in spite of oneself’ while the second kanji, ga, translates to 'picture'. The translation for 'manhua' is approximately the same, and it is said that the Chinese borrowed the characters for ‘manhua’ from the Japanese in the early 1900s (Wong 11). The term is said to have been coined by early 19th century print maker Hokusai Katsushika to describe the action, puzzle, cartoon, and horror pictures of the day (Schodt 35). Just like with American comics, there is a bias against comics as anything other than lowly popular entertainment in Hong Kong and Japan –even built into the name manga!

The significance of the characters for manga and manhua is intriguing, but even more so might be the implications of using kanji for the art of manga and manhua as a whole. Scott McCloud discusses this briefly when he describes the history of written language and points out that “these first symbols –cartoons, really –gradually evolved away from any resemblance to their subject, toward the highly abstracted forms of modern language” (McCloud 131). And while this is true for both the Chinese and Japanese written languages, they remain far more related to their pictorial ancestors than Roman and Greek scripts. This is true not only for the kanji, but for the entirety of the manga and manhua form where the reading of written and drawn symbols in manga in these forms becomes much more interlaced with the symbolism of the ideograms, and even more visual in design.

Scott McCloud discusses this briefly when he describes the history of written language and points out that “these first symbols –cartoons, really –gradually evolved away from any resemblance to their subject, toward the highly abstracted forms of modern language” (McCloud 131). And while this is true for both the Chinese and Japanese written languages, they remain far more related to their pictorial ancestors than Roman and Greek scripts. This is true not only for the kanji, but for the entirety of the manga and manhua form where the reading of written and drawn symbols in manga in these forms becomes much more interlaced with the symbolism of the ideograms, and even more visual in design.

In Japanese manga sound effects are used to direct action and pacing and are written in ways that affect the mood of the story. Notice that in the manga below the Japanese sound effect for ‘zoom’ is shaped to direct the action of the man’s jump. Manga is an extremely consistent form of visual communication, which has sometimes been described as the “inherently ‘cinematic’ nature of much of Japanese culture” (Schodt 25). Osamu Tezuka, one of the most influential Japanese manga artists of all time, has said, “I don’t consider [my manga] pictures… I think of them as a type of hieroglyphics… In reality, I’m not drawing. I’m writing a story with a unique type of symbol” (Schodt 25). Manga and manhua are as much full immersions in visual culture as they are entertainment.

There is a long history to these two forms of visual culture, going back to the 1500s. In Hong Kong manhua developed in a combination of isolation and internationalization. As an island territory and then as a British colony beginning in 1842, Hong Kong has always been separated from mainland China to some degree, until it returned to PRC rule in 1997 (though even then as a special administrative region). Although the oldest ancestors of manhua are mostly from mainland China, there is also an influence of British comic art in their form and publishing today.

The earliest manhua-like arts in Hong Kong include stone carvings, pottery, and scrolls from the Ming and Qing Dynasties, as well as “a satirical drawing entitled Peacocks by the early Qing Dynasty (1643-1911) artist Zhu Da, and a work called Ghosts’ Farce Pictures from around 1771, by Luo Liang-feng” (Wong 11). The art to the left is another work by Zhu Da. Under the Qing and Ming Dynasties, although these arts were often humorous or satirical, they were rarely political. In 1875, with the introduction of Western printing methods to Hong Kong, periodicals and other mass printed works became more and more popular (Wong 12). Along with newspapers that carried the one-panel cartoons that were the beginnings of manhua, small picture-story books called lianhuantu were available for renting from street vendors. These lianhuantu were thought to be “an unschooled medium, meant for a mass audience with little education or aesthetic sophistication,” an opinion that still affects comics today (Wong 12). These were the very beginnings of the manhua form, which was first introduced through weekly satirical journals.

The art to the left is another work by Zhu Da. Under the Qing and Ming Dynasties, although these arts were often humorous or satirical, they were rarely political. In 1875, with the introduction of Western printing methods to Hong Kong, periodicals and other mass printed works became more and more popular (Wong 12). Along with newspapers that carried the one-panel cartoons that were the beginnings of manhua, small picture-story books called lianhuantu were available for renting from street vendors. These lianhuantu were thought to be “an unschooled medium, meant for a mass audience with little education or aesthetic sophistication,” an opinion that still affects comics today (Wong 12). These were the very beginnings of the manhua form, which was first introduced through weekly satirical journals.

One such journal was titled The China Punch, named after the British The Punch, and was aimed at foreigners in Hong Kong. It was very much a colonist’s journal, but “notwithstanding its Western bias, The China Punch is significant because it introduced Hong Kong to humorous and satirical cartoons as a genre” (Wong 13). The comics presented in The China Punch were not manhua, but they influenced Tse Tsan-tai, a Hong Kong artist and a revolutionary friend of Sun Yat-sen’s. In 1899 his satirical comic The Situation in the Far East was printed in Japan to protest treaty ports and the other political outcomes of the Opium War (Wong 13). This work is pointed to as the first official manhua in Hong Kong.

During the early 1900s, as the GMD and the Communists fought over China, many political cartoonists and magazines moved to Hong Kong where they could protest their respective enemies in relative freedom. Throughout the later half of the 20th century Hong Kong remained a safe place to publish material concerning the People’s Republic of China and write cartoons on other political issues. As 1997 approached, and the exchange handing Hong Kong back to the mainland got closer, manhua was one of many art forms used to express the combination of concern and excitement at the return of mainland control. Manhua has been used as an artistic outlet for political feelings as well as for propaganda and entertainment.

In 1927 the Cartoon Association, or Manhua Hui, was established in China and Hong Kong and took on duties of increasing production and readership (Wong 15). During this time, and through the Second World War, manhua were mostly serialized in newspapers or journals like the Shanghai Sketch or its competitor Modern Sketch. In 1928, one of the most famous Chinese serial manhua first appeared, Mr. Wang by Ye Qian-yu (Wong 15). After the war children’s comics and other more commercial forms of manhua became popular. Magazines dedicated to manhua became the new medium for mass readership, including Cartoons World, a manhua magazine for adults (Wong 17).

It is important to note that although cut off from mainland China, and although “Hong Kong’s cartoonists turned to American comics for inspiration and gradually developed a unique hybrid of Eastern and Western styles,” Hong Kong manhua were very distinctive (Wong 17). Some of their specific attributes include an emphasis of Chinese culture and history, and “more panels per page than American comics” (Wong 17). In the mid-1960s more readers became interested in longer stories, more serial-book manhua were published, and a golden age dawned for manhua (Wong 18). This is a trend that continues today, where manhua are sold in magazines that carry multiple, serialized, ongoing stories (although the golden age is said to have been damped by the introduction of television). Today manhua are not only political satire, but also fiction in many genres, and are read by many people in Hong Kong, from businessmen to children.

The history and genre of Japanese manga differs from that of Hong Kong’s manhua. Beginning as early as the 6th or 7th centuries, the early ancestors of the manga were introduced to Japan along with Buddhism. To the left is an excerpt from a Buddhist work entitled “The Animal Scrolls” or “Chojugiga.”  Japanese Buddhist monks would create scrolls about the “six worlds of Buddhist cosmology –heaven, humans, Ashura (Titans), animals, ‘hungry ghosts,’ and hell” (Schodt 29). Zen pictures, or zenga, were also practiced by Japanese Buddhists to aid in the discovery of the spiritual self. The growth of these early art forms was then cut short during the Edo period (1600-1867) when feudal landlords ruled Japan, and art was strictly contained (Schodt 33). In the early 19th century there then appeared woodblock cartoons and ukiyo-e, visual jokes and pictures for entertainment. Also popular during this period were shunga, or erotic picture books (some of the first bound comic books in the world), and kibyoushi, which were small picture books that told a variety of stories (Schodt 36-37).

Japanese Buddhist monks would create scrolls about the “six worlds of Buddhist cosmology –heaven, humans, Ashura (Titans), animals, ‘hungry ghosts,’ and hell” (Schodt 29). Zen pictures, or zenga, were also practiced by Japanese Buddhists to aid in the discovery of the spiritual self. The growth of these early art forms was then cut short during the Edo period (1600-1867) when feudal landlords ruled Japan, and art was strictly contained (Schodt 33). In the early 19th century there then appeared woodblock cartoons and ukiyo-e, visual jokes and pictures for entertainment. Also popular during this period were shunga, or erotic picture books (some of the first bound comic books in the world), and kibyoushi, which were small picture books that told a variety of stories (Schodt 36-37).

Just like in Hong Kong, there was also a Western influence in the history of manga. In 1862 another version of the British magazine The Punch was published, this time in Yokohama, and named The Japanese Punch (Schodt 38). Comic artists for The Japanese Punch are said to have introduced word-balloons to a broader audience, and to have influenced many early Japanese manga artists to use pens instead of brushes (Schodt 41). In these early days, manga mostly appeared in weekly newspapers much like American comics, but soon developed a realm of their own.

It was early children’s magazines that foresaw the future of Japanese comics. These magazines were published with “photo-articles” and “lavishly illustrated stories” and had titles like Shonen Club and Shojo Club, boys’ and girls’ magazines respectively (Schodt 51). After World War II these magazines would begin to publish serial manga stories, which, once completed, could be purchased in a collected volume –the way manga are published in Japan now (Schodt 51).

During World War II, however, manga was used for mainly political purposes as propaganda. It was at this time that “umbrella organizations like the New Cartoonists Association of Japan… were created with government support to unite cartoonists under an official policy” (Schodt 55). These groups served as unions that were controlled by the government in order to support the war effort. As the war wore on cartoonists in Japan were “active in one of three areas: producing family comic strips that were totally harmless or promoted nations solidarity; drawing sing-panel cartoons that vilified the enemy...; and working in the government and military service creating propaganda” (Schodt 56). Manga was limited to these three capacities when the war ended in 1945.

After World War II Japanese comics experienced a substantial boom, similar to the golden age of Hong Kong manhua.  One of the first indicators of this was the kami-shibai, or paper play, a form of outdoor street theater where each panel of a story (set up similarly to a manga) would be shown sequentially in a single frame while the narrator added sound effects and details to the plot (Schodt 62). Manga themselves were also growing in design, capacity, story telling, and length.

One of the first indicators of this was the kami-shibai, or paper play, a form of outdoor street theater where each panel of a story (set up similarly to a manga) would be shown sequentially in a single frame while the narrator added sound effects and details to the plot (Schodt 62). Manga themselves were also growing in design, capacity, story telling, and length.

One of the most influential leaders of this growth was Osamu Tezuka who had a very broad and cinematic style that he used to develop adventure stories, romances, ghost stories, and science fiction (Schodt 64). Manga creators like Osamu began at this time to work either in groups or by themselves, but often with subordinates who were learning the trade or wanted to apprentice themselves as helpers –such groups formed into self-titled production companies (Schodt 142). The manga themselves were available for a short time in pay-libraries, but soon most people could afford to purchase the manga in volumes or monthly manga magazines (Schodt 67). In the 1960s the manga production circuit in Japan had settled into its current configuration: “major book publishers supported themselves with sales of comics, first serialized in magazines and then compiled into series of paperbacks” (Schodt 67). In Japan, the production of comics has turned into an incredibly large business, with hundreds of weekly and monthly magazines being actively published, and thousands of active readers.

Both Japanese manga and Hong Kong manhua have developed into their own cultural forms, and despite substantial internationalization –Japan was occupied after World War II, and Hong Kong was a British colony –both regions have created specific art forms that are culturally personal. The unique forms of manga and manhua, however, are also part of the international genre of comics (or, I could say, American comics, like manga, are part of the international genre of manhua).

If manhua and manga are genres of comics (and vice-versa), with their own unique history and development, then there are subdivisions within the category of ‘manhua’ and ‘manga’ that include political, satire, sports, children’s, science fiction, and action, and girls or boys comics. In Hong Kong, children’s manhua, action manhua, and political manhua are three of the most important (or famous) genres. In Japan the genre of manga is usually subdivided into girls manga (romantic and comedic stories) and boys manga (action and adventure stories). While there is quite a lot of overlap in readership, the manga magazines are sold in this manner. In Japan sports manga and science fiction manga are also prominent genres. The overarching thread of our genre class –genre –found its way literally into the discussion of manga and manhua. The way manga and manhua are labeled and packaged for sale reveals clearly how international systems of labeling are, and how pervasive in multiple cultures.

Of the most popular manhua genres, action stories have become one of the most famous and genrefied types of manhua. These include stories and art about violence, the crime world, and martial arts, but also include stories about ancient heroes and war stories. These stories can be extremely explicit in their depictions of violence (some would say depravity), so much so that “the Hong Kong government amended the Indecent Publication Law [1975], forcing publishers to seal explicit comics in plastic bags,” an amendment that stays in place today (Wong 101). One of the most famous Hong Kong manhua gangster titles is Little Rascals, a series that weathered these publication laws by renaming itself Oriental Heroes and changing the venue from Hong Kong to Japan. Even with these restrictions in place, action manhua remain popular.

Manhua and Manga both share some similar sub-genres, including the very specific Hong Kong genre of card games and gamblers, and the Japanese genre of mahjong stories (Schodt 119). Both seek very specific audiences, usually those who are well acquainted with the games they depict. More widely read are sports manga and manhua that cover activities from baseball (very popular in Japan) and football to tennis and ping-pong. Other specific genres can be found in Japan as well, for instance the zosan manga, or production comic, was one of the most common types of manga published during the World War II, but which dried up after the war ended (Schodt 55). These manga were meant to be propaganda and spur industrial workers on with nationalism and political messages. These genres of manga and manhua are so numerous that they become hard to calculate, and are not even the only way of dividing up manga and manhua.

In Hong Kong and Japan, most magazines are sold as boys’ manga, girls’ manga, or men’s manga. Although in actuality the magazines are sold across demographics (business men buy boys’ magazines, and girls will read both girls’ and boys’ manga), the publishing companies continue to sell manga and manhua based on these gender-specific titles (Schodt 88). Drawing styles between boys’ and girls’ manga and manhua also change; for example, in girls’ manga panels do not hold the action, but fade away and allow flowers, stars, or other design patterns to weave between the scenes. Because of this availability of descriptions and divisions, the sub-genres of manga and manhua are intriguing on a historical level, but their complex labeling systems reveal how genre functions in this system.

| Girls Manhua | Boys Manhua |

|

|

| Girls Manga | Boys Manga |

|

|

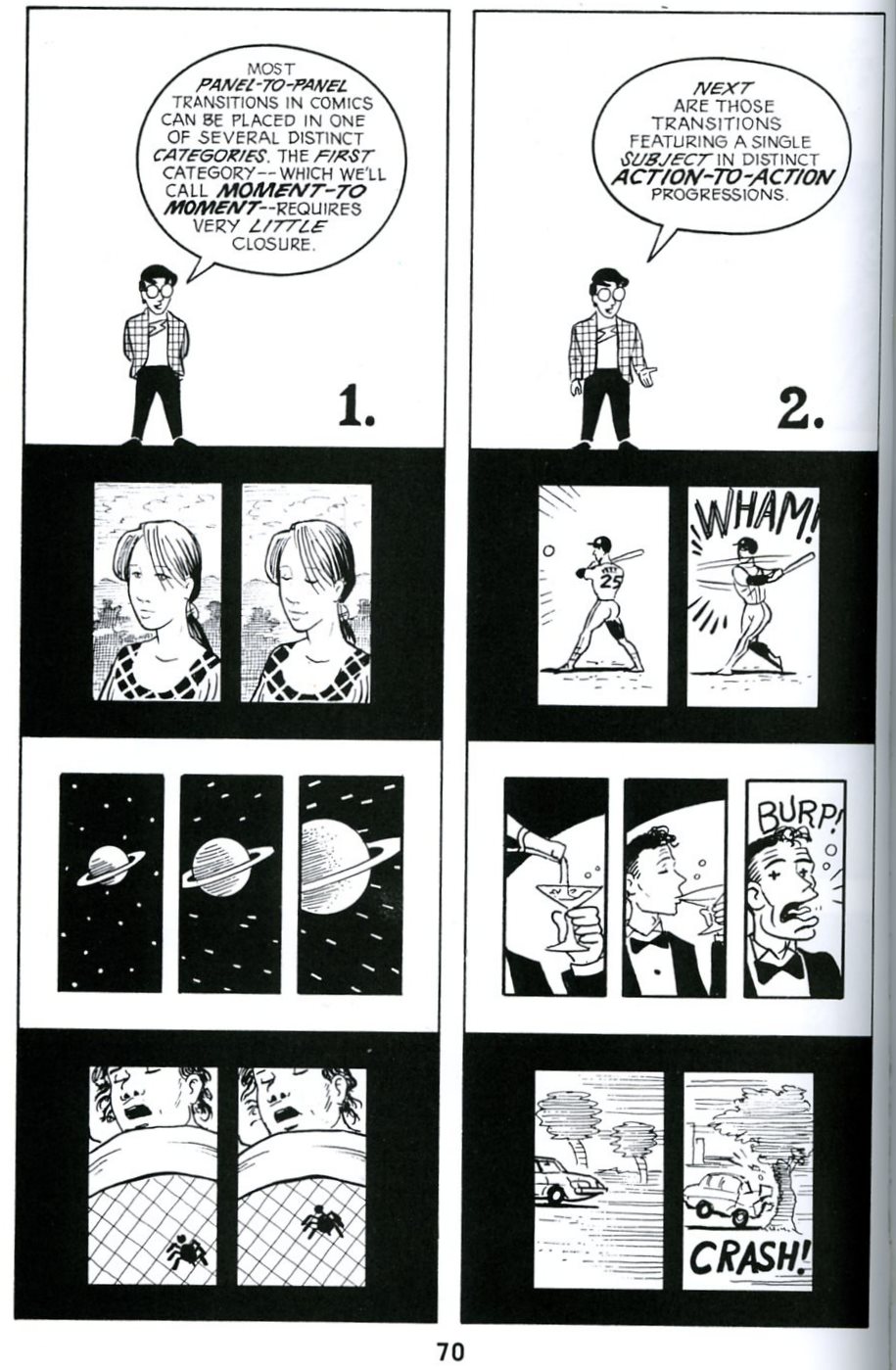

Though manga and manhua pay homage to art found across genres and regions, they contain unique complexities of form. As Scott McCloud describes in his book on comics, there are different kinds of transitions between panels, just as there are different ways of transitioning between shots in a film (please see a collection of his explanations at the end of this paper, labeled ‘Scott McCloud on Transitions’). Most American comics use only action-to-action, subject-to-subject, and scene-to-scene transitions, but manga and manhua use moment-to-moment transitions (ex: between an open eye and a closed eye for a wink) and aspect-to-aspect (ex: multiple actions of the same scene) movement as well as the three previous transitions (McCloud 74-79). Like in the films of Japanese cameraman and filmmaker Ozu, moments are assembled with many shots, or over many panels. This is possible because Japanese manga developed with far more panels per page than American comics, and with an emphasis on atmosphere (remember how the words and ideograms are used to create sound effects that also create atmosphere?).

So the web stretches from international literature to manga and manhua and back to film. The web frames two entire genres --important because they help create the idea of international literature. Their differences and unique attributes are what make them their own broad genres and also what creates their separate identities. It is those identities that, combined with the identities of American comic books, French comics, and more, create a worldwide genre of comics (or manhua, manga, or bande dessinee).

Manga and manhua are genres in one sense and media in another –and often defy both labels. As genres they are part of the international medium of comic-forms, and as media they are playgrounds for the multitude of stories that can be told within their forms. They defy genrefication by being alternatively specific (in language or topic) and broad (in topic and vision). What are left are differences that matter, that make manga and manhua unique and historically significant. For all that they share with American and other western comics, manga and manhua are distinct and artistic contributions to world-comics. As we continue to study genres and media, manhua and manga can give us new questions about world- and historical-genres. Arriving at the center of this web, I notice a new frame surrounding me, one of world-comics, which in turn is framed by our genre-class. What other frames can we add (do we want to add), either to broaden our view, or restrict it?

Scott McCloud Explains Transitions and Japanese Comics:

Works Consulted

Wai Chee Dimock, "Introduction: Genres as Fields of Knowledge." Special Topic: Remapping Genre. PMLA 122, 5 (October 2007): 1377-1388.

Schodt, Frederik L. Manga! Manga!. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 1983.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperPerennial, 1994.

Wong, Wendy Siuyi. Hong Kong Comics: A History of Manhua. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2002.

MacWilliams, Mark W. ed. Japanese Visual Culture: Explorations in the World of Manga and Anime. Ebrary.com [Bryn Mawr College]. New York: M.E. Sharpe Inc., 2008. http://tripod.brynmawr.edu/search~S10?/tJapanese+visual+culture+%28Online+%3A+ebrary%29/tjapanese+visual+culture+online+ebrary/-3%2C-1%2C0%2CB/frameset&FF=tjapanese+visual+culture+online+ebrary&1%2C1%2C

Images Consulted/Used:

Scott McCloud: Japanese comics

http://www.csuchico.edu/~mtoku/vc/Articles/natsume/natsume_intromanga_files/image007.jpg

http://www.csuchico.edu/~mtoku/vc/Articles/natsume/natsume_intromanga_files/image008.jpg

kanji for manga:

http://blog.cleveland.com/andone/2008/07/180px-Manga_in_Jp-1.svg.png

sound effects:

http://ministryoftype.co.uk/images/files/anime.jpg

animal scrolls (chojugiga):

http://www.japannavigator.com/wp-includes/images/pics09/ando2.jpg

toba-e:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fe/Tobae.jpg/180px-Tobae.jpg

http://img405.imageshack.us/img405/9276/12249a2zw7.jpg

modern shonen:

http://www.backon-online.com/images/shonenjump_cover17.jpg

http://asame7.web.infoseek.co.jp/capcomf341.jpg

http://www.rockettubes.net/rescuebaseseattle/mic28p15.gif

modern shojo:

http://img.photobucket.com/albums/v667/gamrage/Hoshi013_23.jpg

http://madinkbeard.com/blog/wp-content/images/okazaki_suppli_1_202-3.jpg

http://kasumimanga.com/images/Vol1_sample_tree1.jpg

modern boys manhua:

http://www.independent.co.uk/multimedia/archive/00018/manhua_18210t.jpg

modern girls manhua:

cover art: http://pics.livejournal.com/saodem/pic/0008301s/s320x240

Early Manhua-like arts:

http://www.chinaexpat.com/files/u659/zhuda_3.jpg

Kami shibai:

http://www.chinatownconnection.com/images/kamishibai2.jpg