October 26, 2014 - 16:58

Laura Swanson’s photography plays with the history of portrait photography and disrupts the viewer’s expectations of how to interact with portrait photographs. To explore this, I look at two very different examples of her work: the first is part of her “Anti-Self-Portraits” series, and the second is part of her series of Bryn Mawr and Haverford students following her work on the two campuses two years ago. I argue that the different goals for each series and the different subject matter impact how each may be read, and highlight the ways photographic portraiture has been used to represent people. The first overturns assumptions about portraiture in an effort to reclaim power for the portrait’s subject and takes a political stance. The second relies on traditional portraiture techniques because it is produced with documentary goals and, I believe in Swanson’s view, is apolitical.

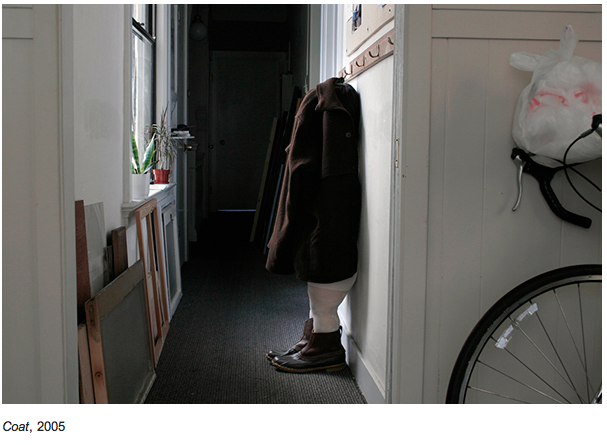

(Coat, 2005)

The first, pictured above, titled Coat plays with the ways portrait photographs and viewers traditionally interact. As an “anti” portrait, Swanson’s face and upper body are hidden completely by a coat. Only her legs and feet are visible. She stands in a narrow hallway filled with frames and canvases. The coat that hides her hangs on a coat hook in front of a window into the hallway. She’s viewed only in profile. Based on the position of her feet, one could presume she faces the left frame of the photograph – head and all – unlike traditional portrait photography in which the viewer gazes at the subject and the subject gazes back.

The lighting of the photograph forces us to shift the way we assume portrait photographs should be lit. If the viewer were positioned in the window facing Swanson, we would be viewing her head-on and in full natural light from the window. Since we view her from the side and down a hallway, instead the viewer is positioned in shadow. The space behind Swanson is also darkened, while the window lights Swanson herself. The lighting from this perspective is anti-traditional in that it comes from the left-hand frame of the picture rather than from the viewer’s position. Our eyes are drawn to Swanson’s lighted form as we’re also drawn to look further back into the darkness behind her.

In other ways, Swanson uses traditional techniques of mirroring and symmetry to compose the portrait. The darkness of the shadow in the hallway, predominantly on the left-hand side behind Swanson is echoed in the dark shapes of the bike frame in the right-side foreground of the photo. The red in the plant pot on the windowsill is echoed in the red on the plastic bags propped on the bicycle handles. Swanson’s figure is made up of a brown coat, white tights, and brown boots, so that she becomes a vertical echo of color. In this way, she reminds the viewer of traditional portraiture while overturning its ideals.

(Kaylynn, 2012)

The second portrait, Kaylynn, evokes an entirely different feeling from Swanson’s self-portrait. Here the subject looks directly at the camera or viewer and the subject’s face is in full view. Unlike Swanson’s hidden features, we see Kaylynn’s full face and upper body, turned a little to the left-hand frame. Kaylynn returns our gaze, but the gaze is just slightly upwards, indicating that camera is above the eye-level of the subject. In this way the gaze avoids being confrontational. The background is spare; the subject is entirely alone in the photograph and only given character by light. The lighting is unusual for a photographic portrait because it comes both from the front lighting the face of the subject, and from behind evoking an angelic glow. In this way, the portrait is reminiscent of painted portraits of religious figures. However, the subject is a student and person of color – identities not typically represented in painted portraiture. Viewed in the context of this series, this isn’t a political statement by Swanson, but simply a documenting of the students and faculty she came to interact with in her time at Bryn Mawr and Haverford Colleges. She adopts the role of photographers who take yearly school photos.

In Swanson’s Anti-Self Portrait, Swanson’s location in plain site of the viewer yet obscured is a conscious choice. She plays with the history of portrait photography as a way of cataloguing peoples and providing opportunity to stare. About the portraits, she says,

“My recognition of this desire [to look at (or look away from) physical difference] is informed by personal experience and by the history of photography, which is riddled with images of the Other. At its most critical, these photographs are a response to the problematic images that gawk at otherness –– images that continue to stigmatize many groups of people” (2005-2008).

In studying her Anti-Self-Portraits and her theorizing behind them, it is interesting to compare her work to the more normative portrait forms that she’s used. Her recognition of the “gawk[ing]” involved in photography is shifted in the second photograph or not as visibly apparent. I would argue that is predominantly because the portrait represents someone without a visible disability and because the purpose of the portrait is apolitical. While the first portrait appears on Swanson’s website under “work,” the second appears on her website under “portrait work.” The distinction to me is that the first is to be seen in the context of the art world and its history of representation (or misrepresentation), while the second is to be viewed as outside of this art context, for use by the subject. The first is acting against a history of photographs of disabled people that are exploitative and pathologizing. The second is in line with family portraits and photos, disconnected from political and public viewing.

What strikes me is that the assumption that the series of portraits of people from Bryn Mawr and Haverford is apolitical ends up reinforcing the idea that these people and this form of representation is normative. And it reinforced the idea that those without visible disability are deserving of representation not afforded to those with visible disabilities. Because the portraits in the second series are in fact public and featured on Swanson’s website, they become part of the visual “rhetoric” of portraiture. I would argue that when people without visual disabilities are featured in traditional photographic portraiture, their perceived physical ability reifies ideas of what is “normal.”

This isn’t to say that Swanson’s self portraits are then within the cultural norms by not traditionally representing someone with a visible disability. Her self-portraits continue to do the work of upending assumptions surrounding the relationship between the subject and the viewer. But I am suggesting that in spite of their differing intents, her “portrait work” may in some ways undermine her “work.” This raises the question: how can one produce both politically informed artwork and apolitical portrait work? And is it possible to do one without undermining the other?

Laura Swanson's work and website can be found here.