November 26, 2014 - 21:20

The (Un)Ethical Representation of an Autist Artist

Amelia Brady-Cole

November 26th, 2014

Iris Grace Carter Johnson, is a five year-old with an incredible talent for painting and has begun to be recognized around the world because of her work. The way she understands colors and how they interact with each other is unusual for a child of her age. Her work has been compared to the work of Claude Monet, and each piece is selling for thousands of pounds. Her mother, Arabella Carter-Johnson, tells a journalist about her daughter’s artistic process. “We realized that she is actually really talented and has an incredible concentration span of about 2 hours each time she paints. Her autism has created a style of painting, which I have never seen in a child of her age. I quickly learned how effective it was as a therapy, to help with her moods and communication” (Iris Grace). Iris Grace’s career is taking off, and all the journalists writing about her can focus on is the fact that she has autism.

Headlines like “The Miracle of Little Miss Masterpiece,” “Silent Tot’s Magnificent Masterpieces,” and “Autistic Toddler’s Paintings Sell for Thousands,” evoke a kind of irrefutable sentimentality that revokes the genuine value of her art. “Sentimentality has inflicted the wonder model, producing the convention of the courageous overcomer, contemporary America's favorite figure of disability. Whereas the wondrous elevates and enlarges, the sentimental diminishes. The sentimental produces the sympathetic victim or helpless sufferer needing protection or succor and invoking pity, inspiration, and frequent contributions” (Garland-Thomson).

It’s a common occurrence for stories of neuroatypical people to be coined amazing or inspiring. It’s a source of turmoil in much of the disability community, and art therapy plays a large role in perpetuating this pattern. In Eli Clare’s book, Exile and Pride, he discusses some of the ways in which our society reinforces the superiority of the nondisabled body and mind. “A blind man hikes the Appalachian Trail from end to end. An adolescent girl with Down syndrome learns to drive and has a boyfriend. A guy with one leg runs across Canada. The nondisabled world is saturated with these stories: stories about gimps who engage in activities as grand as walking 2,500 miles or as mundane as learning to drive” (Clare).

By turning disabled people, who are just going about their lives, into symbols of inspiration, we’re focusing on them “overcoming” their disabilities and denying that it is in actuality the culture that we have created that others, impairs, and disables them. Art therapy is one example of how the superiority of nondisabled people is perpetuated. The process of art therapy depends on the therapist, the age of the child, and the “problem” being “treated.” The therapist will give their client age-appropriate art supplies and a prompt to work from, and then allow them to freely express themselves through the medium. After the pictures have been finished, the therapist analyzes them and works to understand what emotions the pictures represent. These speculations and the conversations the therapist and client have after the child makes the art are then used to develop an effective treatment plan (Art Therapy Journal). The art is used as a means and not as an end.

At the center of art therapy are the byproducts of the act of creating, not on the finished product. There is a way in which this kind of process-centered practice queers the way art is made and how it is perceived. However, there is an inherent lowering of expectation and possibility for the attainment of praise in response to the value of the art itself. By focusing on the process and the psychological and mental "benefits" art therapy can provide autist children, and by labeling their art as therapeutic, their artistic expression loses its ability to be seen as art for arts sake and takes on an air of pity.

Because of the attention Iris Grace’s art has received, her parents are making a huge profit and donations are being made to fund her therapy. This includes her art therapy, speech therapy, and other types of intervention. Though it may not be part of her parents’ plan, the way their daughter’s website displays their child’s work plays up the intended pity response in a big way. If people see a person in distress, especially a child, they are more likely to donate to a cause. By turning Iris Grace’s work into a charity to help fund her therapy, her individuality and personhood are stripped from her and the focus of her audience becomes their desire to lend a hand in “fixing” this child, or helping to aid her in her quest toward a normative life. While people are clearly purchasing her work because it’s beautiful, the underlying message of the website is that by contributing your money, you are helping to fight against Iris Grace’s disability. It’s an issue of ethical representation as well as ethical treatment.

Because Iris Grace is largely nonverbal, and she’s only five years old, she doesn’t yet and may never have the ability to communicate her wishes about what’s done with her art. There are two possibilities of how Iris Grace’s work and talent have been handled. The first is that there has been an assumption made by her parents who are selling her work, by the customers who are buying her work, and by the journalists who are publicizing her work, that she wants to have her paintings released into the world and wants to be a spectacle. The second possibility is that her opinion and desires have not even been considered. As a child, and as a person with autism, she has not yet been given any kind of autonomy or decision-making power. Clearly, it would be impossible for her to run her own art business and career without the help of adults, but the fact that it has already happened without her consent is problematic.

Iris Grace’s parents are not alone in the struggle to accurately and ethically represent their child. Michael Berumbe has written extensively on the topic. As a father of a child with developmental disabilities, he thinks critically about the issue of ethical representation and articulates his stance in a way that can be understood by the average person. “Part of the burden of representation, for human populations that have long been ‘dehumanized,’ is precisely to demonstrate that ‘dehumanized’ people do in fact have feelings and dreams --- just as you do… My job, for now, is to represent my son, to set his place at our collective table. But I know I am merely trying my best to prepare for the day he sets his own place. For I have no sweeter dream than to imagine aesthetically and ethically and parentally that Jaime will someday be his own advocate, his own author, his own best representative" (Berumbe). The only thing parents of autist children can do is try their best to represent their children in the way they think is most ethical. It is impossible to ever represent anyone but yourself in an entirely ethical form. This doesn't mean that autist children should not be represented at all. Parents of children with disabilities must make the choice between imperfect representation and no representation at all.

There is another way in which autist artists have their individuality taken away from them. Many exhibitions of works by autistic artists focus on the idea of autism looking different in every person. Because no two autism diagnoses are the same, the work produced always comes from a completely unique perspective on the world. This framework is problematic because implies that neurotypical people have individuality and unique perspectives whereas autistic people do not. It seems that perceptions of disability often mask individuality and humanity by becoming the most visible or easily recognized aspect of a person’s identity. When all that is visible is one singular identity and the intersectionality of our personhood isn’t considered, we become one-dimensional and easily othered by the people who look upon us. Once a person is othered and placed in a category that cannot overlap with an identity we hold, dehumanization is nearly impossible to avoid.

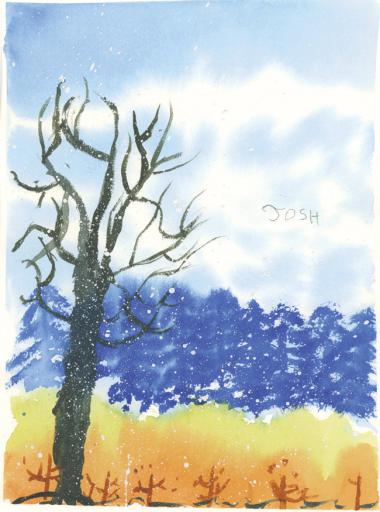

In a collection of art created by trained and untrained autistic artists titled “Drawing Autism,” a recurring theme is self-representation. A question posed by the publisher, Jill Mullin, to many of the artists in the collection is, “Do you think your art helps others understand how you view the world” (Drawing Autism)? This is a pointed question, and one that assumes a difference in the way autistic people view the world from neurotypical people. 12 year-old Josh Peddle responds to this question by saying, “It feels weird when you have autism. I feel silly. It makes me sad thinking about it. People do not understand. Strangers cannot tell by looking at me that I have autism. If I am having trouble, they often want to tell my mom how I should behave. I wish I had more friends that liked me for who I am” (Drawing Autism).

Though this kind of interview question most definitely has a place somewhere, it doesn’t fit alongside the piece of art Peddle chose to present in Drawing Autism. His painting is of a landscape. The focus is on a leafless tree with evergreens in the distance. It’s titled Changing Seasons. It’s possible that Peddle made this drawing in response to feelings he was having about his autism, but the pointedness of this question reveals the therapeutic nature of the collection and the publisher’s motives. Clearly she has good intentions and wants to support members of the autist community, but doesn’t recognize a problem with the therapeutic framework of the digital exhibit she has curated.

The advantages of using art therapy with children are clear. Often with nonverbal kids, many of whom have been diagnosed with some kind of autism, the results of the use of art paired with other kinds of therapy can be great. It can be a valuable tool for assisting therapists in diagnosing and treating clients (Art Therapy Journal). However, the dismissal of the value of the art and the legitimacy of the artistic expression by clients is what is problematic. For children like Iris Grace, who clearly have talent and artistic careers ahead of them, as well as for people who enjoy making art for no other purpose than to create, there needs to be a way to escape the hegemonic construction that there is a dichotomy of art that is valued because of the process, and art that is valued because of the product. In order to break apart this socialized belief, there must first be an effort to deconstruct what it means to create art that is worthy of respect.

Works Cited

“Drawing Autism - 50 Watts.” Drawing Autism - 50 Watts. Retrieved November 26, 2014 (http://50watts.com/Drawing-Autism).

“How Art Therapy Can Help Children.” RSS. Retrieved November 26, 2014 (http://www.arttherapyjournal.org/art-therapy-for-children.html).

"Video on Iris Grace.” Iris Grace. Retrieved November 24, 2014 (http://irisgracepainting.com/).

Bérubé, Michael. 1996. “Epilogue.” Pp. 250-264 in Life as we know it: a father, a family, and an exceptional child. New York: Pantheon Books.

Clare, Eli. 1999. Exile and Pride: Disability, Queerness, and Liberation. Cambridge, MA: SouthEnd Press.

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. n.d. “The Politics of Staring: The Rhetorics of Disability in Popular Photography.” Pp. 56-75 in Disability Studies Enabling the Humanities.