October 8, 2014 - 23:31

Renee by Beverly McIver

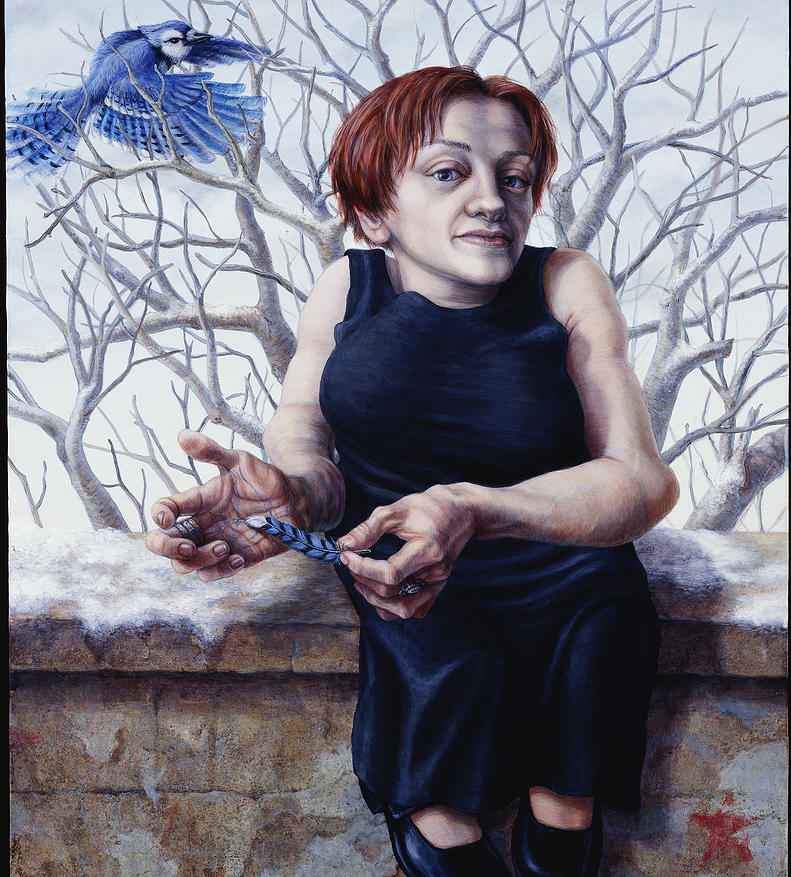

Rebecca Maskos by Riva Lehrer

~

Uncommon Strength and Presence

Portraits represent important people, introducing them to the public as people of worth. Portrait viewers often feel as though they are connecting with an immortalized human in a personal way, as though the viewer is being exposed to the subject in the manner that person wanted to be remembered. The viewer might assume that what is distinct about the portrait demonstrates a part of the subject that you would not notice immediately when meeting them. Working in 2-D, artists must present a personality -- a unique individual -- in a way that makes them stand out from other art as well as other people. The artist must say -- not only is this person worth looking at, but there is something special about them that I want to show you, mainly, a notable personality. When discussing personality, one must recognize that this word has many meanings, referring to a famous person -- especially relevant to discourse on portraiture, describing what makes a person unique, and in an archaic sense -- what makes a person different from a thing or an animal.

In creating portraits of people with disabilities, artists face a slew of challenges. The disabled are frequently depicted in popular media as objects of pity or as people who are disadvantaged and expected to “overcome” their disability. Faced with this standard, an artist must first humanize the disabled person in a way that validates them as a person outside of these characterizations. Occasionally, an artist manages to also explain the person’s identity in this depiction -- not only proving their human-ness, but also elucidating what is unique about them. These thoughtful characterizations of disabled people are necessary for the eventual inclusion of the disabled into society. Without having their physical nature depicted as something normal and worth looking at for artistic and not spectacle-making purposes, the disabled will continue to be othered and marginalized. Without these productive portrayals, the disabled are left perceived as without personalities and without humanity, no different from a thing or an animal.

Beverly McIver and Riva Lehrer endeavor to overcome these challenges in portraits of subjects with disabilities. McIver has painted numerous portraits of her sister, Renee, who has a developmental disability. Lehrer, in her portrait series called Circle Stories, celebrates people who work to redefine how disability is portrayed and perceived in the 21st century. Each confront the challenge of representation in striking ways that contrast one another and invite the viewer to engage more closely with the subject. McIver’s portraits create a dialogue with the viewer about her non-normative use of color to represent shadow and expression, making him or her feel as though they are having an intimate conversation with her subject. Lehrer employs symbolic imagery, focusing less on detailing the person, and more on portraying the aspects of her subject’s personality that you cannot normally see in visual depictions that frame the subject. The juxtaposition of McIver’s “Renee” and Lehrer’s “Rebecca Maskos” act as foils for one another, identifying strengths in each approach to portraying the disabled and their personalities in portraiture.

McIver demonstrates how much she cares for her sister in the attention to detail and expression she conveys in her portrait. McIver seems to have used oil paint in this portrait, which has allowed her to layer color on top of color -- the portrait’s main appeal. Like Rosemarie Garland-Thomas' notion of a frame of honor (27), McIver frames Renee with a golden background. This background evokes sunshine and happiness, giving an air of royalty to the subject; highlighting her skin and contrasting well with her regal purple shirt. Further, Renee seems to be one with the background -- her shoulder fades into the frame. She embodies light and positivity in being one with the background. McIver doesn't include a lot of her subject's body, but the feeling of her pose, indicated by her open shoulders and expressive facial expression demonstrate that she seems inspired or fascinated by the viewer. There is a hint of amusement in her expression that toys with the power dynamic of the viewer and subject of the portrait. Her face is slightly turned, avoiding a confrontational stare, but still demonstrating her control of the situation. She seems to have dark shadows under her eyes and lines that frame her upturned eyebrows. This expression could also be interpreted as surprise, surliness, or amusement. Further, Renee's eyes do not seem to be focusing on the same place, which gives her the effect of looking past the viewer, while simultaneously engaging with him or her. If anything, she gives the air of looking at you rather than you looking at her. The texture of color on Renee's face catches the viewer's eye first, drawing their eye around the whole of it in a waterfall-like pattern that slides down onto Renee's right shoulder, which is more exposed than her left. Her stance -- slightly turned; her face -- off-center; and the unevenness of her shirt seem to demonstrate that she's not a simple person who's easily understood, maybe her personality isn't quite symmetrical. McIver's use of color is the most striking aspect of this portrait. She uses pinks, whites, yellows, oranges, purples, and blues to highlight the curvature of her subject's face, spelling out in detail her expression. These colors point out where the shadows fall and bring certain loudness to the subject's face. McIver’s portrayal of Renee’s personality is dynamic and colorful. The viewer feels connected with Renee and sees her as someone worth respecting, with her kind gaze and pleasant demeanor.

In stark contrast, Lehrer’s uses few bright colors in her portrait of Rebecca Maksos. Lehrer uses muted colors, mainly navy, blue, tan, white, grey, red, and black. This portrait could be easily as powerful in black and white only. Lehrer guides the viewer’s eye around the portrait through the features in the background around the subject, prompting them to consider her choice of imagery and its symbolic implications about the subject. The most prominent feature that guides the viewer’s eye is the tree behind the subject. Without leaves, and coupled with the frosty ledge behind the subject, Lehrer evokes the essence of winter. In this setting, it is shocking to see a blue jay in the sky, as well as a woman wearing clothing for the summer months. The tree frames the subject, giving her an almost halo or wing-like effect. It is important to note that the picture comes with a description that explains that Rebecca has ostogenesis imperfecta, also known as brittle bone disease. One would usually characterize branches in winter as brittle, but despite the setting and lack of leaves, this tree seems vibrant and as alive as ever, with dynamic highlights of color and shadow and sinewy branches. The texture on the branches parallels the curvature of the subject’s arms and demonstrates a similar ability to withstand strain and be flexible. The normative implications that strength is something all should strive for fails to include many, especially the disabled. In a social context, strength is a quality to be admired. Lehrer elucidates in this portrait that Rebecca is able to withstand hardship and is someone to be admired, without ascribing to the normative notion of strength. The subject’s version of strength is more of a tangible feeling not associated with aggressiveness or muscle mass, but of a wise and grounded soul, which ties back to the imagery of the tree.

While she appears down to earth, she also is imbued with a sense of lightheartedness that is depicted through the blue jay’s flight. Further, though her arms have distinct and shaded lines, she is gingerly holding the feather with her left hand and touching it to her palm. This touch seems to have spread blue within her veins, further reminding the reader that she is present and full of life, even in this seemingly destitute environment. Her pose is otherwise relaxed and conversational, leaning on the wall behind her and sticking out her hip. Her face, like Renee’s, is turned, with one side darkened. Her bemused expression and upturned mouth make her appear to be evaluating the viewer, also contradicting the power dynamic of portraiture that deems the viewer in control of the situation. She seems to want to engage in a frank discussion with her viewer. One notices, too, that her gaze is direct and her eye is shaped similarly to the blue jay’s, explaining that the two subjects have much in common with one another. Birds are also associated with freedom and the quality of being limitless. While Rebecca is similar to the bird, she is not without limits, and is very much present on this earth. This juxtaposition demonstrates the subject’s power and the loftiness of her character, prompting the viewer to consider the inaccessibility of striving for a limitless life.

Not only do these portraits illustrate the personalities of two fascinating people with disabilities, but they challenge social norms that guide art and perceptions of power. In this case, the subjects are in power and to be revered; they are not objects of spectacle, they are dynamic humans. McIver’s unique use of color explains more about the subject’s personality than many classic portraits that fail to engage with the subject and seem only provide something to look at. The colors she uses seem to move on their own, arguing that the subject is real and present. Though the portrait of Rebecca has many mute colors, the subject seems full of life, exemplified by the blue in her veins, the liveliness of her hands, and her momentary expression. Both of these subjects are limitless and strong with limits and weaknesses. They embody a new definition of the normative, one-sided, sought-after traits; they are real, tangible, present, grounded, and worth revering.

Bibliography

Garland-Thomson, “The Politics of Staring: Visual Rhetorics of Disability in Popular

Photography.

Lehrer, Riva, “Rebecca Maskos,” <http://www.rivalehrerart.com/#!rebecca-maskos/c9ra>

Accessed 10/8/14.

McIver, Beverly, “Renee,” <cravenallengallery.com/artists/beverly-mciver/> Accessed 10/8/14.