October 9, 2014 - 16:17

To Preface: I'm putting up what I have written of my paper, since I'm unable to work on it any further for the time being (and don't know when I'll be able to get back to it) and figured that, since it's pretty fleshed out already, something was better than nothing. Thus, pardon the complete lack of revision; some parts aren't fully developed, others do not flow particularly well, and points and trains of thought may be repeated. Hopefully I'll be back soon for take two.

Portrait of the heart, Portrait of the Heart: Questioning the Ethics of Veteran Portraiture

The depiction of disability acquired through service during war is a trailhead from which there are countless paths to follow. Many of these paths are problematic, playing up to public’s emotions through dramatizing and even romanticizing war, loss, injury, and heroism. The ethics of portraiture then shift in these portrayals in that a subject may be chosen specifically because of an acquired (often visible) disability, but must then be portrayed without being objectified and reduced to that disability. It is inevitable that gaps will be filled and voids will be left, as there is no one perfect way to portray a theme with infinite, weblike connections between artist, subject, viewer, history, public opinion, reception, intent, and message. A portrait of disability must fit dually into the framework of war and the framework of disability, and serves—intentionally or not—as a narrative of the subject’s past, present, and future. In order to look more closely at how we can effectively portray war, I will analyze two separate portraits of veterans with disabilities acquired in war and the relationships they contain between history, audience, subject, and artist.

Berman’s Portrait of a Heart

At first glance, it is evident that Nina Berman framed this portrait with her subject’s prosthetic leg as the focal point. The angle at which he is sitting (and the fact that the pant leg is rolled all the way up) give a very clear view of the entire leg, and its angling makes it appear larger, as we saw last week with the portrait of Christopher Reeve in which his wheelchair was made to seem dramatically larger than his body (here, his foot appears to be the closest to the viewer). Of not also is that the portrait is literally framing the prosthetic leg; that is to say that the leg is exactly in the center of the picture. The overall message of the image is a negative one; our subject is in a position that clearly depicts stress; notably, his face is not visible.

The picture comes from Berman’s Purple Heart series, a series of "portraits of veterans wounded in the Iraq war photographed at their homes" (Berman), so presumably his amputation came as a result of an injury sustained in war. Thus, from his positioning his unhappiness is evident; it is also highlighted by the color palette of grays and blues. Since his face isn’t showing, it is possible as well that he is more than just upset—that, just as his identity is not visible to us, so he might feel that he has lost some measure of his identity. Indeed, only the amputated leg is visible, indicating that the war-inflicted disability of one leg is more defining than the ability of the other. His positioning and the mood evoked take us back to several other points we’ve discussed in class: although the portrait may be an honest representation of his emotions, it is still clearly negative, once again reinforcing the image of the soldier as the martyr as well as the privilege that comes from having a recognizable, physical disability that can easily be rooted to a distinct cause illustrated by the very title of the series.

Looking specifically at his costuming and the costuming of his surroundings, we see a slice of him in what his day-to-day life, one nearly identical to his life pre-disability save for the crutches in the background (and potentially a cane behind his back; I can’t quite tell?). His clothing is especially telling: by wearing the average clothing of someone in a professional setting, one identity—that of a normative, nondescript person—is made visible. Meanwhile, the other—that of someone with a disability—is easily hidden; were we to see him in this outfit with the pant leg rolled down, his disability would become invisible. In rolling up his pant leg, this “secret,” concealable identity is made visible, as if we are being exposed to a private and vulnerable part of him. In this way, Berman also takes us back not only to the trope of the soldier with the tragic story but also to the idea that such a disability is not merely one to be mourned but also one to be hidden.

Anthony Wallace’s heart, "In His Own Words"

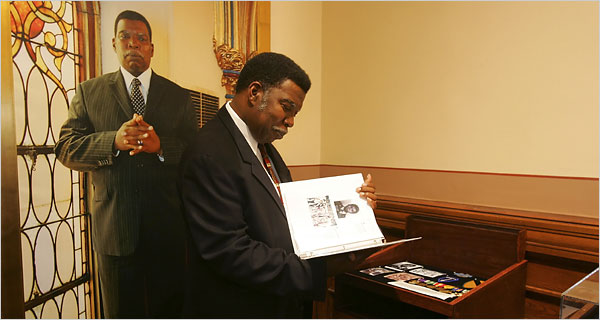

Anthony Wallace views his own exhibit. Photographic portrait in background.

Press Release of Exhibit Transcript of Oral History, on page 18 (from Education Department of Brooklyn Historical Society) Partial Recording of Oral History from ExhibitPhilip Napoli and Sady Sullivan’s portrait of Vietnam War veteran Anthony Wallace goes beyond a physical representation; its utilizes a biography, audio recordings, letters, and other artifacts to recreate his experience—to paint a full picture of his story beyond what art alone can do, a story shaped by trauma, injury, and post traumatic stress. To begin the display, a life-sized Wallace, illuminated by a stained glass window, faces straight forward as the face of the story we, the guests, have been invited into. Notably, Napoli and Sullivan use not a portrait of a young man wrapped in bandages who spent months after serving in a hospital bed but one of a stately, suit-clad veteran who has returned to tell his story and is not to be ignored. We can look at his medals—a Purple Heart among them—and letters before standing on a pair of footprints (which, quite intentionally face Wallace’s likeness directly), at which point an audio recording will start playing from a speaker above us that enables “the visitor [to hear] the veteran’s voice as if that person were standing right there” (Wilson).

And what we are hearing is just as important as the manner in which it is relayed. A major theme in discussions of the Vietnam War is the incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder among those veterans and the difficulty they face in receiving acceptance both because of public attitude towards the war and because of stigma associated with PTSD. What makes Wallace’s portrait so striking, then, is that this imprint is not ignored, brushed aside in favor of telling a hero’s story. Rather, it is prominently featured in the narrative in which he relays his battle with the guilt of having been the only one to survive the explosion of an enemy shell outside his bunker: “The summer of 1970 I wrote President Nixon and told him who I was… And that there were three other people who were in the bunker and I was able to give two names” (Education Department). His full recording goes on to detail his journey in contacting the families of those two and the visit with one of those families that at last absolved him of his guilt. Centering the entire account around the way the war remained with him after leaving the battlefield builds a compelling and multifaceted chronicle; it functions both to highlight the pain and mental scars left on veterans and to relay how these scars have been woven into their lives.

The story we see still does have a “happy ending,” so to speak; it ends with the effective dissipation of his survivor’s guilt. We still don’t know if his PTSD manifested itself in other ways, as is often told of other Vietnam veterans, or if the shells embedded in his body that got him his Purple Heart affect him in any way today. As a result, part of the rhetoric evoked is indeed the heroic tale of a veteran who overcame a roadblock. But in some ways, this portrait presents a noteworthy alternative in the portraiture of disabled veterans: one, it highlights a disability often erased, and depicts it in the most effective possible way—whereas a photograph is appropriate for showing an acquired physical disability, as with Berman’s portrait, the multimedia exhibit and featuring of an oral history is much more efficient for illustrating acquired mental disability. The portrait also functions to humanize an oft-distanced war. We meet Wallace; in essence, he becomes Tony to us. He is human. In his article “Stories of Veterans, Aloud,” Michael Wilson writes, in reference to Tony’s physical injury, that he is “part man, part artifact,” in that he “carries a lot more metal than [his Purple Heart] in his 59-year-old back and hands.” But, as we see him, Tony is not just part man and part artifact because he carries the weight of the war in his body every day. He is part artifact because his life is preserved in a museum and part man because that same museum displays his humanity, his struggles both during his time serving and in the years post-war and the way they resonate with him today.

Contextualization: Framed by the Public?

In order to analyze and compare the two most accurately and thoroughly, consideration of context is essential. The portraits are shaped by the level on which the artist is connected with their audience as well as the audience’s relationship to the group of veterans to which each subject belongs and, tangentially, the wars in question themselves. Berman’s portrait was part of a series called “Purple Hearts—Back from Iraq” that depicts veterans (all Purple Heart recipients) of the Iraq war with visible disabilities acquired during their service. Napoli and Sullivan’s portrait was part of a museum exhibition designed to illustrate a controversial war as it pertains to local history. Both of these were made with the public eye in mind, as they were displayed in public galleries; moreover, they are, at their core, highly charged in that they depict veterans who have received Purple Hearts (a symbol of valor and sacrifice) and who fought in wars with distinct leanings in our collective memory.

In addition to being made for a gallery, Berman’s has an additional slant that borders on the precipice of sensationalism: in addition to its display in an art gallery, her works were featured in a New York Times article and in People magazine, where the rhetoric of romance reveals conscientiousness of public sympathy in showing veterans who “push through” their wounds to live normal lives: “Ms. Berman took this picture…on assignment for People magazine... But the published portrait was a convivial shot of the whole wedding party. Maybe the image of the couple alone was judged to be too stark, the emotional interchange too ambiguous” (Cotter). The American collective public’s perception of Iraq veterans is one coated—in spite of disapproval of the war—with tear-jerking homecoming videos (link to TV show) and an intimate connection to the war induced violence through constant media connection. Berman feeds into this perception by presenting a pain-wrought yet anonymous soldier’s humanity, safely conveying that he is a martyr who gave his leg to serve our country and is now, even back in the safety of his bed, suffering alone in a dark and painful place. But owing to our inclination to admire our Iraq veterans, the audience set to pity him, his Purple Heart, and his prosthetic leg, to embrace him and mourn for him because he, too, sees it as a sacrifice.

On the other end, Napoli and Sullivan do not seem to be seeking pity for a loss; rather, they, along with their subject himself, demand respect for a gain and dignity for those who previously had their dignity taken away due to a lack of public support. Their many media flesh out a fuller story, the portrait selected to put a face to the story is stately and poised, and the recording itself relays a story straight from facts, devoid of dramatization and mourning over losses. The exhibit is in part so successful because of Wallace’s agency. It is undeniably for the public eye (and ear), especially as it appeals to the hometown hero ethic. Although its call for the public to remember and respect veterans may be seen as another trope, it is still about acknowledgment of veterans who have previously erased and acknowledgment of a condition almost always erased because of the difficulty in recognizing, confronting, and accepting something that can’t be seen and something that affects behavior instead of aesthetic appearance. Wallace speaks openly about his survivor’s guilt on his own terms, focusing on how he came to terms with his past and moved forward. Napoli and Sullivan likely made decisions to emphasize the positive rather than the negative for the sake of the audience; Sullivan even wrote of her intent behind the exhibition, “‘Meeting’ eight people who were touched by the Vietnam War, visitors are prompted to consider the on-going impact of the Vietnam War in the lives of Brooklynites, from their memories of the war to how it affects them today” (Sullivan). But rather than completely coloring the audience’s perception of Wallace, the curators allowed a for great deal of give and take in striking the balance between what would most appeal to the audience and the story Wallace wants to be presented in his portrait.

In looking at the larger picture of how disabled veterans are portrayed, the artists in question present styles of portraitures that each have their own merits and emphases. Napoli and Sullivan highlight history in their exhibition, telling Wallace’s individual story while also fitting it with eight others to convey a shared idea. In choosing to focus on this one part of his life’s story, one aspect of disability acquired through war is highlighted—the lasting mental damage it incurs—while any others are erased. berman emphasizes heroism and injury; while her journalistic leaning is apparent in her presentation of disability as dark and tragic, she also humanizes our youngest veterans in the context of their disabilities and conveying a political message about the devastating violence of war and its ongoing tendency to produce disabilities. The contrast in these two paintings can be summed up through the Purple Heart: both soldiers have the medal, but while Wallace’s story is painted around the heart as the event that caused his guilt, Berman’s subject’s story is one of the heart—it is even more about the heart than the subject himself, given that his prosthetic leg is the focal point and we don’t know his name or see his face. Each of these methods is particular to context, of course, and the relationships (both those that already exist and those the artist wants to create) among subject, artist, and viewer. And these relationships are central to evaluating how we present war: there is no right or wrong way. Is it problematic that so often visible, isolated disabilities with obvious causes are favored over mental disabilities that force us to confront the lasting trauma and emotional pain that can destroy a person? Absolutely. For this reason “In Our Own Words” is successful because it presents deeply personal, intimate stories, and fits them into a compelling larger narrative about a war and its negative imprint in our collective memory. But on an individual level, that oft-problematic portrayal is necessary because the subjects are only human. To discern between the two, it is not enough for an artist to be concerned only with their audience. The subject must come first and foremost, through agency or just input, because in the end, it is not our tale to fabricate, and it is not the artist’s fact to manipulate: it is the veteran’s story to tell.

Works Cited

Berman, Nina. Purple Hearts. Digital image. Nina Berman. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Sept. 2014.

Cotter, Holland. "Words Unspoken Are Rendered on War's Faces." The New York Times. The New York Times, 21 Aug. 2007. Web. 09 Oct. 2014.

Education Department 2010. In Our Own Words: Portraits of Vietnam Veterans. New York: Brooklyn Historical Society, 2010. PDF.

Sullivan, Sady. "Brooklyn’s Vietnam Veterans." Web log post. Brooklyn Historical Society Blog. Brooklyn Historical Society, 30 Sept. 2009. Web. 05 Oct. 2014.

Wilson, Michael. "Stories of Vietnam Veterans, Aloud." The New York Times. The New York Times, 13 Dec. 2007. Web. 05 Oct. 2014.