Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Notes Towards Day 1: Reading Images, Imagining Forms

I. Reading an image....

II. Reading Another...

What did you see?

In each picture?

Comparatively?

"I am intrigued by traditional museum conceits – classification, juxtaposition of words and objects, the relationship of the collectors and curators to their collections – in short, the grey area between a rational scientific system and human idiosyncrasies. Private and institutional collectors share the same instinctive hunger – to seek, to find, to classify" (from Rosamond Wolff Purcell's Arcane Treasures).

Vegetable Lambs and Elephant Birds: Classifying the In-Between

(Carpenter Library, December, 8 2009):

on the choices of display and categorization, and the fluid boundaries between art and science

"...in the eastern part of Chinese Tartary, there is a species of fern furnished with thick tubers, which being surrounded on all sides by yellow wood, and thin chaffy scales, are often raised so high above the ground, that the roots beneath bear some resemblance to legs fixed in the soil … It is not therefore surprising that the imagination of the superstitious and ignorant should transform this curious vegetable into a voracious sheep" (1828; rpt. in The Vegetable Lamb of Tartary).

Hydrocephalic child whose head has opened like a flower

![]()

II. We start w/ these ambiguous, in-between images, to figure what this course is about--

the imaginative act of classification: what it gets us, how it limits us--and how we use it

to manage the monstrous, the unclassifiable.

"As soon as genre announces itself, one must respect a norm...one must not risk impurity, anomaly, or monstrosity" (Jacques Derrida, “The Law of Genre,” Glyph 7: 1980).

OTOH, one might say that the act of classifying is itself deforming, reductive, incomplete (=monstrous?). As William James (whom I'm teaching in another course this semester) said,

"the basis of every classification is the abstract essence embedded in the living fact,--the rest of the living fact being for the time ignored by the classifier. This means that none of our explanations are complete. They subsume things under heads wider or more familiar; but the last heads...are mere abstract genera, data which we just find in things and write down" (The Will to Believe, rpt. WWJ, 320)

This is a course about the usefulness of genera, in general,

and about the literary classifications we call "genres" in particular.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary,

fr. OF. gen(d)re (F. genre) =

Sp. and Pg. genero, It. genere,

ad. L. gener- stem form of genus race, kind

GENS

A clan or sect; a number of families united by the ties of a supposed common origin, a common name, and common religious rites. Hence employed to designate any similar aggregation of families.

1a. Kind, sort, class; the general gender: the common sort (of people). Obs.

LADY MORGAN Flor. Macarthy (1818) IV. iii. 144

But what is the genre of character...which, if in true keeping

to life and manners, should not be found to resemble any body?

T. MOORE (1856) VII. 273

Two very remarkable men...but of entirely different genres.

b. spec. A particular style or category of works of art; esp. a type

of literary work characterized by a particular form, style, or purpose.

III. To think about genre, in other words, is to think about kinds and sorts.

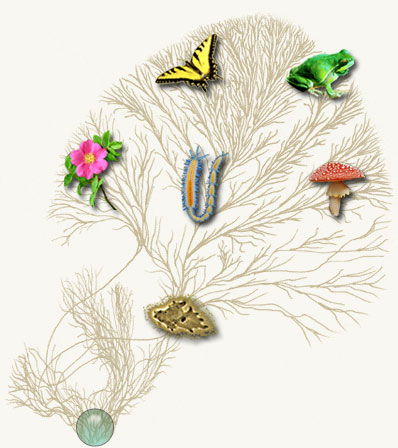

So: let's do some sorting. We could start historically, with Darwin's Tree of Life...

The Darwinian theory of evolution (used most enthusiastically in Ferdinand Brunetière’s 1890 “L'évolution des genres") has been reinvented by virtually every student of genre since (epics--> novels --> movies, etc.)

I could review the conventional European generic divisions, and describe the logic of their differences,

how much they depend on silent reading, or on local divisions between prose and verse:

- lyric/drama/epic (narrative)--> speaking for oneself, as another, about another

- poem/play/story/essay (fictional/non-fictional prose)

- romance/realism/naturalism

- romance/comedy/tragedy/satire (irony)

(we will do that later in the semester, for sure...). But let's try something a little more fun (and a little more personal, a little bit more troubling?).

William James (also!) said, "Individuality outruns all classification, yet we insist on classifying every one we meet under some general head...the life of philosophy largely consists of resentments at the classing, and complaints of being misunderstood" (The Pluralistic Universe, rpt. WWJ, 483).

Let's see about this. Write down 6 words (nouns or adjectives) that you use to identify yourself:

attributes that are important to you, and that you are comfortable using.

Let's put these on the board, trying as we do so to go up "one level of abstraction"-->

what are the kinds of categories that we used to name ourselves?

Two scribes? who will try to draw a site map from the categories we name?

Are the relationships among us best represented by a table, or a grid, or a tree...?

If we were to organize a museum, based on these categories, what form would it take?

The Wagner Free Institute of Science

Go 'round, naming ourselves and our categories...

How many "kinds" do we constitute?

What are the grounds for our groupings?

What is the relationship of our various identities to one another?

(Are they all relational?)

How would you describe the taxonomy/ies we've self-organized into....?

(See Taxonomy--Wikipedia

Taxonomy Lab: The "Nuts and Bolts" of Taxonomy and Classification

Bloom's Taxonomy: A Classification of Levels of Intellectual Behavior )

What matters in the categories we make,

when we discuss our identities and those of others?

How do we construct them?

What categories did we use/fail to use?

Conventional 6: race (ethnicity)/class/gender/religion/sexual orientation/disability

Are other categories more important than these?

Why avoid some of these? (too important? too scary? too obvious?)

What proportion of the categories are visible/invisible?

What proportion of the categories do we occupy willingly/unwillingly?

What proportion are "natural," imposed?

How did we arrange them in relationship to one another?

(How might we re-arrange them?)

Are our taxonomies hierarchical?

With sub/supertypes,

parent-child relationships,

satisying increasing numbers of constraints?

Or flat? Or...?

IV. Why'd we do this?

To get you thinking/doing something experiential.

To remind you that you know quite a bit already, from your life experience; and

to remind you that what you know is infinitely revisable, in exchange w/ others.

And that there's been lots of interesting work done in these areas,

where we can learn more....

So...what have we learned?

For starters: categorization can begin

- "platonically": from the "top-down"--

a priori principles, catagories, into which we then put ourselves.

(But how many categories can each of us occupy simultaneously?

If we were building that "science museum," how many rooms would feature you?)

- "aristotle-like": from the bottom-up--

from practice/ reports of what we observe about ourselves and ourselves,

which we then sort into categories.

Is there a causal relationship among those two procedures?

How much are the categories "inside" determined by those "outside"?

How free are we (or might we be) from socially determined categories?

What all this has to do with GENRES:

- they exist at various levels of abstraction

- belong to discourse communities, not individuals

- involve a (moving!) spectrum of sameness & difference/identification & division/recognition & novelty

- are a lot about expectations (about how texts are read: the "uptake").

read Wai Chee Dimock, "Introduction: Genres as Fields of Knowledge" and Stephen Owen, "Genres in Motion." Special Topic: Remapping Genre. PMLA 122, 5 (October 2007): 1377-1393, and make your first on-line posting.