Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Week One (Thurs, 1/20): How Do Texts Evolve?

How Do Texts Evolve?

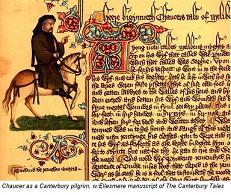

Before printing was invented, manuscripts of important books were copied by hand. This introduced errors, some random, some probably on purpose. Are these changes in some ways akin to mutations in DNA and evolution through descent with modification? (from a page on Darwin Literature, and Language: to discuss...)

I. First, some coursekeeping:

welcome back!

anyone new? (sign-up/in sheets, w/ usernames)

many of you registered and posted, as requested,

introducing yourselves--> there's a nice variety among us,

where we come from, where we'd like to go--

which we will draw on, play w/, use

(along w/ some remarkable overlaps in names!)

there were strong themes of sports, and of traveling,

along w/ some interesting orientations-->

ckosarek: I'm on a "need to know" basis with the world

senior11z: I feel as though there are many possibilities and unknowns to the universe .... I will continue to verbally oppose trying to define the undefinable .... For example ... We cannot possibly know (yet) why the universe does what it does when stars move around .... Who are the engineers in the Factory of Gravity? I don't think it is wise to assert knowledge of the hows and whys of universal workings when there are too many unknowns (not to mention that hairy subject, religion).

... a few (other!) large questions we'll get back to in time-->

Erin Washburn: I am most interested in the interplay

between evolutionary imperatives and our personalities.

any as-yet-unresolved problems

w/ the process of posting?

(reminder that you can change your password and your user name)

if you haven't introduced yourself on-line yet,

please do so over the weekend

also go again to the on-line conversation and post again, by Sunday evening, either your reactions to this week's in-class conversations,

your initial responses to next week's readings, or anything else (relevant) you're thinking/reading about; we are asking you to do this every Sunday evening this semester (this will give us time to organize the class discussions around your interests and questions)

for Tuesday (and Thursday) also please read,

from On the Origin of Species,

Darwin's Historical Sketch --> Ch. IV (pp. 79-177)

(you can skip/read Carroll's introduction, as you like/need/want....)

Paul: any particular instructions on how to read/what to read for?

want to finish up (heh heh heh--go a little further with?)

that story you were telling us about evolution as a way of being....?

(just some background for thinking about what it

might mean, to think about literature evolutionarily....?!)

Okay, so...

Paul's been inviting us to think about evolution as a way of being--and of thinking--and of being educated.

On Tuesday, mediating the differences of opinion among us about the meaning of the word "evolution" --

- =all change

- actively trying to change

- being alive

- involving fitness

- creating new things

- becoming more complex

- becoming "better"

- "no being, only becoming"--

Paul asked how much we can make of the commonality,

on all levels, of the observation that everything is changing.

What/how much can we make of the observation

that we ourselves are living in the midst of all that change,

both responding to and contributing to it?

kgrass: our evolution is not only caused by how

the environment changes us,

but how we change our environment.

"Supposing it's true"--

what do you expect to get out of this course?

what do you expect to put into it?

what will be your role in shaping it?

...my particular portion of it?

What might "thinking evolutionarily" get us,

in terms of understanding literature?

Will it provoke new questions,

and new ways of answering them?

Or entirely new ways of exploring literature,

that refuse any settled answers?

Let's think about this together for a bit...

beginning w/ a

![]()

When I say the word "literature,"

what are the first three words that come to mind?

Write them down, please.

What have we got here?

Would you characterize our current

thinking about literature as "evolutionary"?

Do the same thing for "science": write down three words.

What's like/what different?

Where are the overlaps, divergences??

Is one term more "evolutionary," more "change"-friendly, than the other?

What are the differences between these practices?

What are the similarities?

Of special interest here may be the role of "the crack" (cultural background, personal temperament, individual creativity) as a "feature" of, rather than a "bug," in the process.

|

"scientific statements are ... provisional stories, reflecting human perspectives ... differences among people are an asset to the process" (Paul Grobstein, Science as Story). |

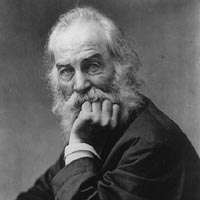

| "I like the scientific spirit—the holding off, the being sure but not too sure, the willingness to surrender ideas when the evidence is against them: this is ultimately fine—it always keeps the way open ... to try over again after a mistake—after a wrong guess …. the readiness to yield, to see what they might have excuses for not seeing. All modern science is saturated with the same spirit, and in this exists its excuse for being" (Horace Traubel, With Walt Whitman in Camden, 1888-92) |  |

differ from the "literary" one?

From our on-line course forum:

alexandrakg: I haven't really thought about how the concepts [of evolution] could be applied to literature.

phyllobates: I am excited to ... use my love of biology to help cultivate a better understanding and appreciation for English.

mgz24: I'm really excited ... to get a better idea of how non science people

look at scientific ideas and apply them to the world around us.

Dawn: Why choose between science and humanities when you don’t have to?

Let's test out our understanding of literature (and how it works on us, and whether that's an "evolutionary" process, and how reading it relates to "doing science"), by engaging, together, in the task of reading a poem (or two).

We'll start w/ an easy one.

After we finish off Darwin, we will read Daniel Dennett's book on

Darwin's Dangerous Idea, which begins this-a-way:

"We use to sing a lot when I was a child, around the campfire at summer camp, at school and sunday school, or gathered around the piano at home. One of my favorite songs was ...

Tell me why the stars do shine,

Tell me why the ivy twines,

Tell me why the sky's so blue.

Then I will tell you just why I love you.

Because God made the stars to shine,

Because God made the ivy twine,

Because God made the sky so blue.

Because God made you, that's why I love you.

This straightforward, sentimental declaration still brings a lump to my throat--

so sweet, so innocent, so reassuring a vision of life!"

That's Dennet's reaction to the song. What's yours?

What did you think/feel/experience/reflect on as I sang the poem to you? What did it put you "in mind" of?

What did you hear?

What observations can you make about the poem?

What summaries can we make of those observations?

What effect did the reading have on you?

What does the poem do?

What does it mean?

How does it achieve that meaning?

For example: who is speaking?

To whom are they speaking?

What are they speaking about?

Where are you in relation to speaker/audience/object?

What is the most useful context ("crack")

for understanding this poem?

What might you research,

to understand the poem more thoroughly?

Let's try this process again,

on a slightly more complicated text:

There is no Frigate like a Book

To take us Lands away

Nor any Coursers like a Page

Of prancing Poetry--

This Traverse may the poorest take

Without oppress of Toll--

How frugal is the Chariot

That bears the Human Soul!

Same questions as before:

What's your reaction to this poem? What did you think/feel/experience/reflect on as I sang it to you? What did it put you "in mind" of?

What do you hear?

What observations can you make about the poem?

What summaries can we make of those observations?

What effect did the reading have on you?

What does the poem do?

What does it mean?

How does it achieve that meaning?

Who is speaking?

To whom are they speaking?

What are they speaking about?

Where are you in relation to speaker/audience/object?

What is the most useful context ("crack")

for understanding this poem?

What might you research,

to understand the poem more thoroughly?

Finally:

How do you feel, as these questions are

being asked of you??

Fear of

...all that space?

...all that you don't know/need to know/

need to know how to look for, in order to respond?

...all you don't know about relevant context?

"Meaning is context-bound....context is boundless;

there is no determining in advance what might count as relevant"

(Jonathan Culler, Literary Theory).

[Two contexts for --my reasons for choosing-- this poem: it was written by Emily Dickinson, then quoted in an novel by Richard Powers, Galatea 2.2, in which a computer is trained to take a graduate-level exam in English; the poem is introduced toward the end of the novel, when the project is becoming poignant...]

Our conversation a demonstration of Reader Response Theory:

- meaning is not pre-determined

- it comes into existence when a text is

read & responded to - focus on the transaction readers make with texts,

ways they actualize them in their own experience - meaning persistently revised as readers compare, collate their readings

- searching for common patterns, recognizing

when the patterns break down - how it works: see Louise Rosenblatt's 1938 Literature as Exploration and Jane Tompkins's 1980 anthology, Reader-Response Criticism

- why it works--as in Paul's story of science--

depends on the encounter between the "crack,"

the heterogeneous personalities of readers

and the indeterminacy/ambiguity of language

(=the space for making meaning). - I offer it to you as an "evolutionary" way of reading:

provocative of new meanings, rather than a search for the old.

|

".... a novel is a two-way street, in which the labour required on either side is, in the end, equal .... Readers fail when they allow themselves to believe ... that fiction is the thing you relate to ... seek out when you want to have your own version of the world confirmed and reinforced ... we have to ask of each other a little bit more"

|

What differs, when you conduct a scientific experiment, read a science text, interpret a poem??

Try reading Darwin, for Tuesday, like a novel--"as

a two-way street"--and let's see what emerges!