Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Notes Towards Day 23: The Wounded Storyteller

| |

I. Before we address some of these questions re:

why this novel, in particular? and what contribution

it might make to the evolution of stories, in general...

a little light on the remaining course requirements:

Third (3-4pp.) paper due @ 5 p.m. Mon, Apr. 20:

on some aspect of the evolution of literary stories that particularly interests--or is useful--to you. Submit a hard copy and

post a copy in the course web exchange, tagging it

"Evolution and Literature Web Paper 3."

Tues, Apr. 21 & Thurs. Apr. 23:

"summative" conversations about what we've learned

Tues, Apr. 28 & Thurs. Apr. 30:

Spontaneously formed emergent groups of four or so students each should

prepare ten-fifteen minute presentations reflecting on their

experiences over the semester. Presentations should encourage, in a

provocative and entertaining way, further story development on the part

of others in the class.

Jackie: we are directing the evolution of this course and causing each other to evolve in thought...controlling and experiencing evolution, perhaps more intriguing than simply studying it

5 p.m. Saturday, May 9 (seniors);

12:30 p.m. Friday, May 15 (all others)

Fourth (10-12 pp.) Paper and Portfolio Due

The Wounded Storyteller; or,

"What Happens When the

Protagonist is a Psychoanalyist"

"Without your wound, where would your power be?"

What is the relationship between trauma and storytelling?

Let's think together about the ways in which

storytelling might heal...or wound further?

Hustvedt, "Extracts from the Story of a Wounded Self," A Plea for Eros: Essays: "I'm afraid of writing...because when I write I am always moving toward

the unarticulated, the dangerous, the place where the walls don't hold.

I don't know what's there, but I'm pulled toward it....The writing self

is restless and searching, and it listens to voices."

BUT

"Trauma isn't part of a story; it is outside story. It is what we refuse to make part of our story" (The Sorrows of an American, p. 52).

BUT

"Trauma doesn't appear in words, but in a roar of

terror, sometimes with images. Words create the anatomy of story, but

within that story there are openings that can't be closed" (p. 85).

"Telling always binds one thing to another. We want a coherent world, not one in bits and pieces" (p. 276).

Echoes here of our conversations about Whitman, so full of "merging," because so troubled by the world's "divisions"....

a longing, a sadness, seems to underlie his exuberance.

as destructive and as healing.

Let's look @ that process.

The Sorrows of an American?

(so awkward....

wherefrom? whereto?)

The Sorrows of Young Werther

What traces of Goethe's text can you hear in this one?

How might Werther function as an ancestor for Erik?

How might the resolution of Erik's plotline

be different? (particularly "American"?)

they haven't moved....The characters...seem stuck in isolation.

Cf. Joanna: one of the reasons I enjoyed this novel was because it traces his individual evolution backwards.... on page 232 after Erik wakes up from a dream...in which he saw himself, his father and his grandfather. He says, "Three men of three generations together...inner cataclysms I had associated with two men who were no longer alive. My grandfather shouts in his sleep. My father shoves his fist through the ceiling. I quake"... this convergence of three individuals....resulting in the individual he is.

"I thought about...the earlier generations who occupy the mental terrain within us and the silences on that old ground, where shifting wraiths pass or speak in voices so low we can't hear what they are saying" (p. 278).

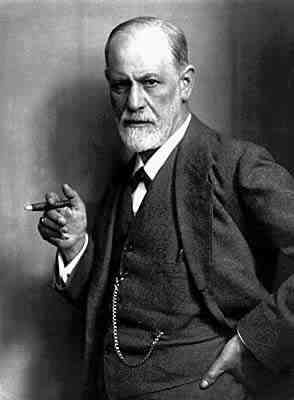

(1856 – 1939)

What do you know about "the talking cure"?

About the profession that Erik practices?

How does it "work"?

What relationship does it bear to literary analysis?

To scientific practice?

To what degree does Erik practice on himself?

"identitytheory.com": a literary website, sort of:

interview: Siri Hustvedt:

At the root of this novel is Hustvedt's oft-stated fascination with "why do we become who we are?"

thing that is the "self"?

What can we say about the

process of getting to know it?

His [father's] was the illness that besets the

intellectual: the indefatigable will to mastery. Chronic and incurable,

it afflicts those who lust after a world that makes sense....my mother...did not have to pursue it. "There are so many things," she said, "that we'll never know" (p. 176).

If we think of this existence of the individual as a

larger or smaller room, it appears that most people learn to know only

a corner... (p. 219).

the distance needed for humor is always missing from dreams....How strange the mind is (pp. 251-2).

"Kierkegaard...'s always had doubts that [the internal and the external] are the same"...."We all have secret drawers"...."and most of the time they are never found....We're always looking for one person when there's more than one, several contentious voices in a single body...all at once" (Inga, pp. 252-3).

It's a miracle when the passions of two people actually collide (p. 276).

There was resistance in [Miranda's] character...and a will

to independence that meant no one would be allowed to tell her story

for her (p. 279).

Burton told me about the many hours he had spent in the streets as Dorothy, his second self, a homeless woman he had named after the girl from Kansas who travels to Oz....my friend had whole territories within him I had never known about. He didn't think of Dorothy as a disguise anymore...but as aspects of himself come to light, both mad and feminine. "There is a delectable, yes, positively chewy pleasure to be derived from raving...from a lunatic discourse that swells up from God-knows-where....I reveled...in the lugubrious, doleful invisibility of my station...the Nobody effect...the lot...of the unseen, the unknown, the unsignified, and the forgotten" (pp. 290-1).

It was snowing...it struck me as a moment when the

boundary between inside and outside loosens, and there is no loneliness

because there is no one to be lonely (p. 301).

The passages in the book from Lar Davidsen's

memoirs are taken directly from my father's text...In this sense, after

his death, my father became my collaborator (p. 306).

Only by keeping alive the

strangeness of that other person can eroticism last....attraction

remains because there's something about him that I can't reach,

something strange and estranging....this is my call for eros, a plea that we not forget ambiguity and

mystery, that in matters of the heart we acknowledge an abiding

uncertainty...a story of exciting thresholds and irrational feeling

(Siri Hustvedt, "A Plea for Eros").

alternately constructing boundaries to keep others out,

and experiencing a world without boundaries.

In telling the story of the bounded self,

Hustvedt crossed many boundaries, drawing

on social science, science and literature.

She wove together American social history (immigration, 9/11),

several literary ancestors (Goethe)....

and what about Whitman?

What grandfatherly role might he have

played in the generation of this text?

"I was the man. I suffered. I was there..."

How does a person lead a coherent life with a stable self...?

Normal life includes making sense of fragmentary memories....fixity arrives only through the task of giving the story to another person....the tale must become comprehensible to a listener.

This story we call the self and articulate as I...is fraught and fragile, and we must fight to keep it together.

....our wholeness and continuity aren't givens but made in us and by us...the self is an entity under threat and the trick of piecing it together...is rooted in the other, where we find a mirroring wholeness, dialogue, and finally story. The journey in the book is from "it" to "I" to "we."

We see that process of deliberate self-construction @ work in this novel, which is structured in part like an autobiography, in part like a mystery...will he find out his father's secret? Will that change his understanding of his father? Will he then know him better? Will he know himself better?

We see it also in the juxtaposition of several different forms of discourse, spanning the spectrum from close-to-the-unconscious to deliberatively distanced consciousness: from Eggy's childish associations ("tying everything together"--p. 270) to the father's distant journal entries ("On the fifteenth of that same month, my father recorded an emotion"--p. 12).

make up Erik's interiority, his dream-->waking life.

What relationship might we see (or imagine?) between Erik's "cracks" and those Paul described as being central to the practice of science? What function do the cracks "in" our personality serve? How are they like/different from the cracks "of" personal temperament above?

![]()

Leonard Cohen

Thank god, then, for the serpent, for the sheer, unstoppable storytelling drive that is independent of plot outlines and thematic schemes, the hidden story that comes snaking in through any ready crack. (Michael Chabon, Maps and Legends: Reading and Writing Along the Borderlands, 2008).