Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

sdane's blog

Two Silences

Sometimes people talk all the time in class, while still staying silent.

Class discussion is about sharing thoughts and ideas, but sometimes it is also about sharing yourself. Now that we are already three weeks into the 360 experience, it is becoming incredibly clear that more than one kind of dialogue occurs in our classrooms. This is true of many discussion-based class settings, but the intimacy and intensity of our cluster of courses makes these different kinds of sharing even more apparent. What I am still not sure of – but am very interested in exploring – is to what extent these two modes of discussion are intertwined, and whether one is even possible to do one without the other. Dissecting and analyzing readings or books on their own is important (and is what I am usually referring to when I talk about class discussion). But telling personal anecdotes, and relating readings, theory, and overarching concepts to our own lived experiences gives a window into how we relate the subject matter to who we are.

Prison education as conscious raising

One thing that really struck me about the Jones and D’Errico article was the director of a prison-based higher education program who is quoted as saying “They don’t tell us how to teach, and we don’t tell them how to lock people up.” The more I think about it, the more I think that higher education in prison should assume this role. Jones and D’Errico grapple with the question of whether or not resources should be used to teach incarcerated individuals, but I think a much more important question is: if education programs exist in prisons, what kind of programs should they be? I have a really hard time applying ideas of reform and rehabilitation from 200 years ago to our exponentially larger criminal justice system today. I think that, at least in the US, using education as a way to carry out Freire’s idea of dialogical education could be very powerful. We have a huge problem of racialized and gendered incarceration, of over-incarceration, of a privatized industry being given incentives to put even more people in that system. Shouldn’t education in prison be used to counteract that? To allow for dialogical conscious-raising, and to teach about the realities of the situation? Maybe prison-based teachers shouldn’t literally be telling prison wardens how to do their job, but shouldn’t they start a dialogue about whether the “business of locking people up” needs to change? Rather than going with Frank Hall’s proposal of putting prisons in the middle of college campuses, I think there needs to be a focus on figuring out wh

Avatar

![]()

In trying to choose my avatar, I started to think about what represents my interests and what I enjoy doing – and the first thing that came to mind was my love of traveling. I googled “map” and this was one of the first images that came up. So, the compass represents the traveler in me, but since uploading it I’ve also been thinking a lot about Johnny Cash’s song “Folsom Prison Blues.” I feel a huge amount of empathy for that man stuck in Folsom Prison hearing the sound of the train everyday – I know that when I’ve been stuck in institutions (hospitals) the realization that traveling continues to happen on the outside is very demoralizing. The compass is also interesting in that it is also a reminder that white/Western privilege seeps into all areas of our lives. North is always on the top of a compass, and maps usually scale up the size of North America and Europe. It also reminds me of the fact that travel in itself is a very privileged activity that most of the world doesn’t have access to. I haven’t really reconciled this yet – the idea that I only have the ability to do something I love because of where I was born – but I’m glad this 360 is sparking the question.

Ramona

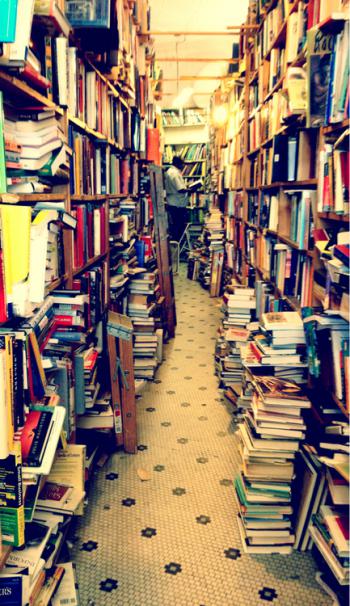

In Anne’s Silence class we’ve been talking a lot about poetry, and the idea that there is silence on the page surrounding the words in a poem. In some ways, the white silence around a poem gives the words themselves added weight, because the noise and distraction of typical prose is stripped away, and all that is left are the most important thoughts. I found a similar phenomenon to be true when reading the “Prisoners of a Hard Life” graphic novel, but rather than being surrounded by emptiness, the words were attached to illustrations. Growing up, I never read comic strips or any kind of graphic novel, but I have come to really love their poignancy since taking an English course that largely focused on a graphic novel about the Weather Underground. Stories mirroring Latisha’s, Denise’s, Ramona’s, Angelica’s, and Regina’s are relayed in innumerable scholarly works about the prison system, but somehow their intensity seems much more subdued compared to a comic with illustrated faces jumping out of every page. Ramona’s story is especially heartbreaking to me because I’ve done a lot of work with sex workers and there is an incredible irony in the fact that carrying around condoms – which can not only protect their own health, but is an incredibly effective public health strategy – can also get women arrested for solicitation.

The "Dialogical Method" and Children

The discussion between Shor and Freire on dialogical education continually brought up questions still lingering from our partnered discussions in class yesterday about Cook-Sather’s article. I am very interested in both how student voice can lead to participatory learning and how the classroom can become a setting for egalitarian dialogue. However, in reading both articles my initial reaction was to think about how these ideas can be applied to early childhood education, which might make their implementation less straightforward. Freire explains that “dialogue is a challenge to existing domination,” implying that the power imbalance between student and teacher can be broken down through dialogue-education. He acknowledges that at all levels of learning there is an intellectual boundary between student and teacher, but doesn’t delve into the very real power imbalance that exists between very young children and adults. Presumably teachers can still “relearn” material from five or six year old students, and dialogue is possible in primary school classrooms, but can young students truly have a voice in their education? As much as I think that these concepts are important for all levels of education, I am having a hard time reconciling them with the incredibly imbalanced relationship between children and adults. In many ways this power imbalance is inevitable, so how can real dialogue and participation exist within an inherently unequal framework?

Silence

I was very struck by Anne’s idea that speaking up in class is akin to sharing, while staying quiet is selfish – somehow keeping brilliance under lock and key, and not giving the rest of the class access. I’ve never had a problem with talking in class, especially since coming to Bryn Mawr, but I often wish I could edit myself more and filter the ideas in my head slightly better before blurting them out. As much as I recognize that silencing oneself is not always a good thing, especially if it is out of censorship or fear or anxiety, I often find it helpful to just shut up and listen. When I silence myself in the classroom at any given moment, I notice that it tends to give someone else the opportunity to speak and share an idea. So is the converse true? Can my voice silence others?

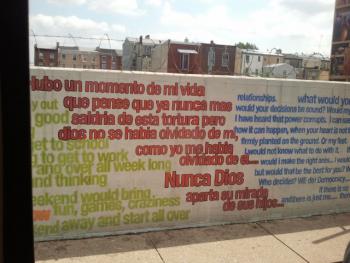

Language

At the beginning of her essay Anna Devere Smith explains that when she started her project she was “not as interested in performance” as she was in language. This immediately struck me because I’ve always considered speech and the use of language to be a type of performance in and of itself. Language goes beyond words – we express ourselves through intonation, body movement, pitch, and facial expression. We are always theatrical when we talk. We are performing. The dichotomy Smith initially presents between the actor and the character is therefore confusing to me because I really do think that we are all playacting ourselves in everyday life. She goes on to explain that “the act of speech, then, does become performance” in reference to seasoned interview subjects who spit out sound bites with ease. But we’re all acting all the time, and the types of criticism Smith encountered during her performances of “On the Road” are censures that most people have encountered at sometime in our life. We are all characters of ourselves which is why its possible for everyday people to be “not black enough” or “too Jewish” in our speech and affectation even when we’re not standing on a stage.

- « first

- ‹ previous

- 1

- 2

- 3