"There can be no love without justice. Until we live in a culture that not only respects but also upholds basic civil rights for children, most children will not know love. In our culture the private family dwelling is the one institutionalized sphere of power that can easily be autocratic and fascistic. As absolute rulers, parents can usually decide without any intervention what is best for their children. If children's rights are taken away in any domestic household, they have no legal recourse. Unlike women who can organize to protest sexist domination, demanding both equal rights and justice, children can only rely on well-meaning adults to assist them if they are being exploited and oppressed in the home" (hooks 19-20).

Diving into hooks' all about love: New Visions, I was struck by this take on the role of children, and the idea that by virtue of their position and vulnerabilities they can so easily become oppressed within the home. Though I never agreed with the notion of parents disciplining their children through physical punishment, I hadn't thought about this so distinctly as abuse, or that using the phrase "tough love" as an explanation is just a means of justifying this abusive behavior. Reading this, it made so much sense--if we can justify our ill treatment of children with the rationale that they "need to learn" because their brains haven't developed enough to understand the world yet, we begin to enter a dangerous zone where violence toward adults with developmental disabilities could be justified by the same logic. I began to think more about all of the connections I have seen as a student in disability studies between developmentally disabled adults and infantilization. So many of these adults are cared for in private settings (or private institutional settings) where a caregiver can exercise their power at will. Adults with developmental disabilities that impede their ability to express and advocate for themselves are at a further disadvantage because they cannot name the abuse they are facing.

I wonder how to apply this thinking to ideas of teaching and learning. In the case of children, what is the role of adult educators? Is their responsibility to treat young students as people with agency and rights born in part from a need to counteract or undo the abusive marginalization potentially put upon them by the parents? And in the case of my placement at the center, my desire to speak to the participants on equal terms and as the older people they are seems all the more urgent.

Comments

childism and infantilization

Submitted by alesnick on March 1, 2016 - 08:24 Permalink

This thoughtful postcard which so conscientiously makes the bridge from hooks to your field work brought to mind the work on Young-Breuhl: http://ideas.time.com/2012/04/26/childism-the-unacknowledged-prejudice-against-kids/: "But unlike most of those who suffer from racism or sexism, children are not yet political thinkers and actors. They depend upon adults for the articulation and protection of their rights, and they depend on adults for survival and loving care. Every adult citizen is, in this sense, a representative for children."

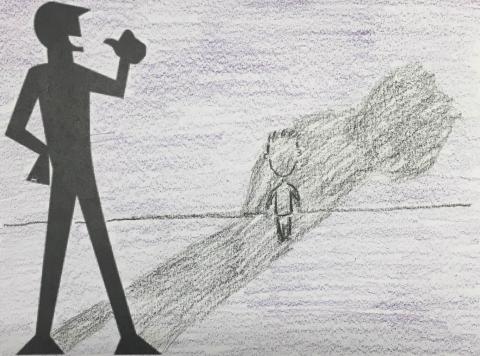

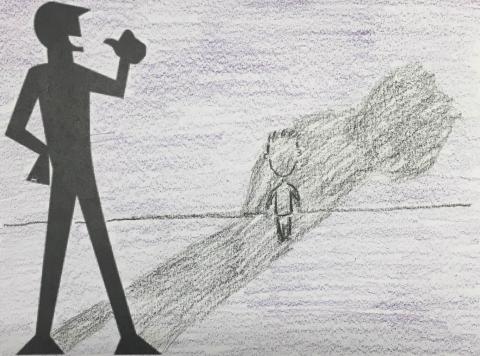

Really appreciating the visual work here, too, and the way this motif is growing :)

Finally, yes, how to think about these questions with the urgency they demand and with the calm and receptivity also necessary to good practice in the placement?