December 19, 2014 - 13:56

Abby Rose

Identity Matters 360

Kristin Lindgren, Sara Bressi Nath, Anne Dalke

December 19, 2014

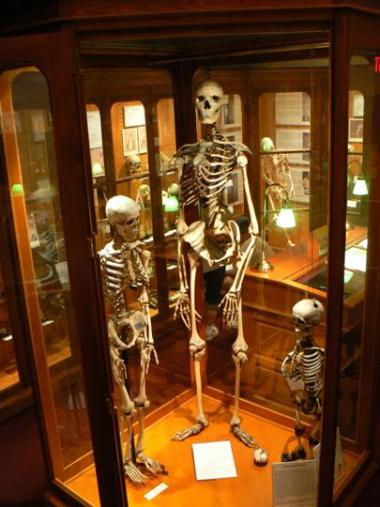

Mary at the Mütter: A Freak of the Night

While walking through the unsettling array of skulls and skeletons and fetuses and in glass boxes at the Mütter Museum, a world-famous institution that capitalizes off of the display of impaired and “abnormal” bodies, one cannot help but feel as though they are walking through a modern day freak show. During my visit to the Mütter, one spectacle stood out to me the most above all else: a colossal glass cage that serves as the resting place of three bodies. One: a skeleton of the “average” human; two: a skeleton with gigantism; three: a skeleton with dwarfism; and four: the petite, fractured skull of a baby no more. What intrigued me the most at first sight of this cage was the tiny head set at the feet of a tiny woman — who were these people? A curt description next to the woman proclaimed that the smallest skeleton was of a woman named Mary, found in a brothel, died after a failed childbirth. The tiny skull on the ground? Her aborted baby. Because of her lower class and dwarfism, Mary has been exploited by the Mütter Museum through its general enfreakment of all disabled bodies on display, its inadequate “medical” representation of her body, its lifeless biography on her final days, and its blatant disregard for her baby’s humanity.

A ticket to the Mütter Museum provides a full day of staring at disabled bodies, but the act of gazing at people with physical abnormalities seldom “[broadens] to envelop the whole body of the person with disability. … Because staring at disability is considered illicit looking, the disabled body is at once the to-be-looked-at and not-to-be-looked-at … Staring thus creates disability as a state of absolute difference rather than simply one more variation in human form.” (Garland-Thomson 57) During their visit to the Mütter, the normalcy of the likely able-bodied museum attendee is affirmed. Visitors will see the subject’s disability because the Mütter ensures that is the first thing to grab their attention, but will not often look further to see the person as an individual. As an establishment that profits off of the enfreaked display of disabled bodies, whose design highlights physical differences as worthy of encasing in a glass menagerie that is mostly accessed through an insidious descent into a dimly-lit den that houses "medical mysteries”, the Mütter Museum exhibits disability as detriment, a horror, a freak show. The lives of the human beings behind the glass are lost, caught in the space between medical and marvel. "At the same time, staring constitutes disability identity by manifesting the power relations between the subject positions of disabled and able-bodied” (Garland-Thomson 57). Not only is a non disabled visitor affirmed in their normalcy, the inherent privilege and power that comes with able-bodiedness comes into play as well. There is a reason it’s them in the museum and not me, right? This sentiment is reinforced by Mary’s juxtaposition with the Kentucky Giant and a normative human frame. Another individual whose body was procured without consent, the Kentucky Giant (formerly known as Martin Van Buren Bates) was a man whose skeleton stands at seven feet eleven inches. His position between Mary and the normative body dramatically emphasizes the physical aberrance of people with dwarfism and gigantism in comparison with the average human.

While society has placed value in ability over disability, similarly distorted power dynamics also come into play when class is introduced. One of the only details included about Mary’s life before the Mütter is that she was discovered in a house of prostitution. Universally, prostitution has been cast as a demeaning profession unworthy of respect, in spite of the fact that it is one of the longest running occupations in history. Although this representation of prostitution is an unfair generalization, it is true that many women (and men) have little choice but to enter it for lack of another path to survival. As a woman with dwarfism in the early 1900s, Mary most likely did not have a wide variety career choices, not unlike many other people with disabilities throughout time. While she may not have been born into poverty, she was living in it at the time of her death; the fact that she was living in a house of prostitution gives an index to her class and subsequent exploitation as a sex object. As a little person, Mary definitely would have been treated differently in the brothel than her normative-bodied coworkers. If people with dwarfism received little esteem and humanity in greater society, a prostitute with dwarfism would have been seen as even less worthy of respect. By including just the bare minimum of information about her life and beginning her biography with the fact that she was a prostitute, the typical visitor at the Mütter already sees Mary through a tainted lens. It almost acts as a justification for her macabre display in the museum, suspended from the ceiling by a metal and plastic cord that is visually reminiscent of tweezers pulling a specimen out of a jar. In her death as in her life Mary is depicted as an object, nearly inhuman, and unworthy of reverence.

The biography included in Mary’s display is an unsatisfactory attempt to remember her life. “As Adam Zachary Newton has pointed out, ‘getting someone else’s story if also a way of losing the person as ‘real,’ as ‘what he is’; it is a way of appropriating or allegorizing that endangers both intimacy and ethical duty’” (Couser 21). By summarizing Mary’s story in a simple placard without her consent or her real life story (whether personal or medical), the Mütter has completely abandoned the necessary intimacy and ethics described by Newton. One rationalization of the diminishing of personal stories into medical histories is that it is therapeutic for the subject and the audience. Turning Mary’s story into a medical marvel could then be seen as righteous because it serves to educate the people; her own personal narrative is sacrificed for the “greater good”. Furthermore, the depersonalization of individuals’ stories is often justified in the medical realm in the name of objectivity. It would be too difficult to continue to view Mary as a specimen if she were to have more than a whore-house and an abortion attached to her name, would it not? However, the display's blatant lack of information on the struggles that Mary endured in her daily life due to her dwarfism completely delegitimizes these justifications. Had Mary’s display been for the sake of medical education as the Mütter so clearly claims, the information displayed in her glass casing would have had her actual medical history on it as opposed to a half-hearted description of her last painful days on Earth.

Besides the year and location in which she was found, Mary’s biography just barely extends to include the heart-breaking, gruesome tale of her miscarriage and eventual death. The placard states that Mary was admitted to the hospital to deliver a child. Because she was unmarried and employed as a sex worker, we can assume that her pregnancy was the result of her work and a factor that she had little to no control over. In spite of the fact that her baby was a byproduct of her exploitation as a prostitute, it does not change the fact that she was still a mother with a connection to her child. According to the short biography, Mary’s pelvis was structured in such a way that she could not give birth to her baby vaginally, so the doctors performed a cranioclasia; this means that while her baby was still in the womb at full term, its skull was fractured and the baby was killed in order to facilitate its delivery. However even after her child’s head was crushed inside of her body, Mary still could not give birth and thus required a cesarean section. Lamentably, Mary died three days after this surgery. Although there is potential for both empathy and medical education in her tale, the Mütter Museum does not give testament to Mary’s undoubtedly agonizing and undeniably tragic final days. Not only does the museum fail to honor Mary’s life appropriately, they show flagrant disrespect for both Mary and her child by carelessly placing her baby’s salvaged skull by her feet. This unceremonious display of a life lost in a traumatic struggle is the epitome of disregard for the sanctity of disabled lives.

"The Mütter Museum helps the public appreciate the mysteries and beauty of the human body while understanding the history of diagnosis and treatment of disease.” This is the mission statement for the Mütter, but serious lack of medical information accompanying the figures on display and even greater lack of respect for the “beauty of the human body,” this statement comes across as a poorly-attempted lie. Mary’s poorly executed display along with the Kentucky Giant is just an excuse for a modern day freak show, and nothing more. Mary’s life, her baby’s death, and her dwarfism — the reason for her admittance into the museum — are far from “appreciated” in this institution. Although her lower class status as a prostitute led to her body being taken against her will, I doubt that her depiction would be much different if she were a priestess procured by the museum. In Mary’s case, her profession only adds to her sordid image as promoted by the Mütter and allowed the curators to look past her baby’s humanity. To the Mütter, it seems as though the disabled bodies, regardless of consent, status, or background are simply oddities to be ogled.

Works Cited

Couser, G. Thomas. Vulnerable Subjects: Ethics and Life Writing. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2004. Print.

Snyder, Sharon L., Brenda Jo Brueggemann, and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson. "The Politics of Staring: Visual Rhetorics of Disability in Popular Photography." Disability Studies: Enabling the Humanities. New York: Modern Language Association of America, 2002. 56-75. Print.

Comments

Great work

Submitted by PIlar Bailo (not verified) on May 8, 2017 - 09:40 Permalink

Nothing to add, just congratulate you for your moving article. The bodies of the women are always another's matter, just like if, by the fact of being able to give birth, that was not just our choice.

Please forgive my poor english. Thanks a lot for your work.