Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Wonderland and the Parody of Meaning

(sorornishi.blogspot.com/2008_08_01_archive.html)

Alice’s experiences in Wonderland are free from most of the norms and expectations that guide our lives and for that very reason are both marvelous and disconcerting. There is an unfettered joy as well as a continual disorientation that the reader experiences vicariously through Alice of never knowing what will come next, of realizing that the only certainty is uncertainty--that what one thinks will happen certainly will not. The world that we think we know, which we define logically through cause and effect, and that we ceaselessly seek to tame through definition, is subverted and replaced by a mad rush of unsequenced and inexplicable events. Along with Alice, we encounter a place that is seemingly lawless, whose nebulous experiences spawn from the subconscious and perhaps even more fundamentally from that most basic mystery that is the only core to existence.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland parodies, I think above all else, the human effort to create an organized universe in which our experience can be rendered rational. We have devised a language that not only arbitrarily symbolizes the world around us, but also incompletely represents it, and we use language to construct narratives that we take to be true reality, instead of some selective and laughably minute version of reality. Carroll’s continual plays on language throughout the book, especially in using words with multiple or ambiguous meanings, divert the dialogues between characters from any anticipated route by the reader, and thus mock the supposed logic and consistency of language, as well as narrative itself.

For instance, when Alice engages in a conversation with the March Hare, their dialogue quickly becomes an exploration of the nature and meaning of communication through language. Following the Hatter’s statement of a riddle at the mad tea party, Alice exclaims:

“…I believe I can guess that."

“Do you mean that you think you can find out an answer to it?” said the March Hare.

“Exactly so,” said Alice.

“Then you should say exactly what you mean,” the March Hare went on.

“I do,” Alice hastily replied; “at least—I mean what I say—that’s the same thing, you know.”

“Not the same thing a bit!” said the Hatter. “You might just as well say that ‘I see what I eat’ is the same thing as ‘I eat what I see’!” (60)

This exchange between Alice and the March Hare parodies the idea that language is a clear and precise mode of communication. Alice finds that the meaning of her words is lost, or at least confused, through the act of interpretation by the one with whom she is speaking. Alice soon discovers that conveying her thoughts to another is not a simple process in the least. In fact, her attempts at conversation throughout the book are repeatedly frustrated. Though the dialogue between Alice and the March Hare is an exaggeration of the problems of communication, it highlights the fact that attempting to say what you mean (or mean what you say), and have another understand what you mean, can be a highly ambiguous process that reveals the inconsistencies and opacity of language.

The linguistic plays throughout the text also result in a narrative unpredictability for both Alice and the reader as even the concept of selfhood, and thus character, is challenged. Take, for example, Alice’s encounter with the caterpillar:

“Who are you?” said the caterpillar.

This was not an encouraging opening for a conversation. Alice replied rather shyly, "I—I hardly know, sir, just at present—at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.”

“What do you mean by that?’ said the Caterpillar sternly. ‘Explain yourself!'

"I can't explain myself, I'm afraid, sir," said Alice, "because I'm not myself, you see." (39)

In this dialogue, one of the most basic of human assumptions is challenged—that of consistent identity. Ever since Alice’s entrance into Wonderland, she has become less and less sure of who she is. The various substances that she consumes continually alter her size and thus her self-definition. On one level, this phenomenon can be read as a simple reflection and exaggeration of a child’s confusing experience of maturing, that of adjusting to a sense of self within a continually changing body. More universally, it challenges the notion that we ever have a fixed identity, that the constant change inherent to experience makes any self-definition contingent upon circumstance and perception.

In this sense, might the insistence upon fixed identity and strongly held values in society be seen as a defensive posture, one that counters a much more ambiguous and unnerving reality of flux and unknown forces operating beneath the veneer of our seemingly ordered world? As we are thrust into Carroll’s wonderland, a place of dreams and as such an extension of our subconscious, we are forced to encounter the irrational and unexpected. Dreams create alternative spaces in which our personas shift. We lose our sacred sense of belonging in an environment to instead feel uprooted and lacking in control, given over to the whims of our most hidden and indecipherable desires and fears, all magnified and warped by the imagination. Alice’s experiences thus reflect our own deeply felt uncertainty in the face of an inverted and mutated reality, one that our dreams reveal to us in profound and startling ways.

In a book as playful and often nonsensical as Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, which represents, or at least plays upon the idea of dreams, the reader is presented with a unique and somewhat paradoxical problem of interpretation. As readers, we are driven by the often insatiable need to find meaning in a text, to somehow satisfy ourselves through the act of interpretation. Yet, by resisting traditional conventions of narrative in which there is typically some sort of character development and a stable notion of space and time, Alice in Wonderland defies definitive interpretation. In a way, it is hard not feel as if the reader, too, is being addressed, when the King states during the trial, “If there’s no meaning in it…that saves a world of trouble, you know, as we needn’t try to find any” (100). Rather than being purely nihilistic, there is something freeing in the notion that meaning must not necessarily be the goal of all experience. There is a way in which the reader is liberated from her usual role of imposing a reductive explanation on a text by the often absurd and unpredictable nature of Carroll’s work. If, however (as is too often the case), we must insist on some sort of message or meaning, let it at least be one suited to the open-ended and playful aspects of Carroll’s writing in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Carroll wrote his books for children; perhaps, then, it is to a child’s sense of awe and possibility that he would urge us to return, or at least to that ideal of a child’s view of the universe one in which nothing is improbable and everything is potentially a novel object of fascination.

Work Cited

Carroll, Lewis. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass.

London: Orion Publishing Group, 1993. Print.

Comments

Finding Meaning is Taking Control

Could our impulse to find meaning within a nonsensical situation be a sign of an underlying thirst for control? We construct our reality (at least partially) by finding patterns from our own observations and comparing them with others' accounts. I believe I would be correct in stating that our brains are hardwired for finding patterns, even in "higher" functionings. Language, for instance, is constructed through patterns. In mastering these patterns, we learn how to communicate with others who understand these patterns.

In trying to find meaning within Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, we try to find patterns that correspond with our knowledge and our conceptions of reality, our sphere of control. Or, is this something entirely otherwise?

Defensive posturing

sgb90--

What I admire here is your assured analysis of the most profound levels of parody in Alice in Wonderland -- its challenge to our efforts "to create an organized universe in which our experience can be rendered rational," in particular to our "insatiable need to find meaning" in a text like this one, which so "defies definitive interpretation."

Particularly astute, I think, is both your recognition of the joy that can arise (along w/ disorientation) in encountering such an "unsequenced and inexplicable" universe; and your strong suggestion that our beliefs in transparent language use -- not to mention our belief in our own consistent identity -- might well constitute a "defensive posture, one that counters a much more ambiguous and unnerving reality of flux and unknown forces."

Where I'd nudge you to go next is in facing up to the implications of your analysis for your own analytic writing. I asked, in my response to your last paper, If the self, as you show, can no longer be said to have "a singular identity," can you even continue to write papers in which "one" argues? If it is no longer valid for us to claim a "constant self," what become the new grounds for "integrity" (=integer: one)? You promised to continue thinking about what you characterized as those "tricky/somewhat paradoxical" questions, so I'm suggesting that we head together back into that space.

You take your deep analysis of the "highly ambiguous process" of "arbitrarily symbolizing" and "incompletely representing" the world around us to the point of saying that it can be "freeing in the notion that meaning must not necessarily be the goal of all experience .... the reader is liberated from her usual role of imposing a reductive explanation." Great! But then you bring your line of argument back around again to the conventional posture: "If, however (as is too often the case), we must insist on some sort of message or meaning...."

Why insist? Is that the case here and now? What sort of valid intellectual work might be performed on texts that challenge the validity of language and narrative, that mock the consistency and transparency of intellectual work altogether? If, as you say, "Alice’s experiences reflect our own deeply felt uncertainty in the face of an inverted and mutated reality," is the most appropriate response really one of re-instituting what you have called a "defensive position"? Are there alternatives?

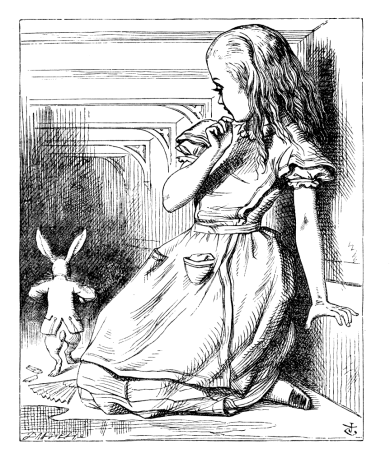

See my comments on rmeyers' Defining Dreams (which covers much of the same territory you do); I review there some linguistic material which celebrates the productivity of inconsistency and opacity. There are also two "cracks" in the form of your paper that seem to offer some possibilities in this regard, by playing with the context of your argument. First, there's your use of that initial image, filled with clocks (which led me to expect a paper I didn't get, about the fluidity of time). Secondly, there's a formatting inconsistency: some of the paragraphs are single spaced, some double (hm ... might we say that there's a "communication problem" between you and the software, which is "misinterpreting" your intentions? Computer language differs, of course, from natural language, in aiming for NO slippage a'tall...!)

"There's a crack in everything, that's how light gets in ...."

Leonard Cohen