Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

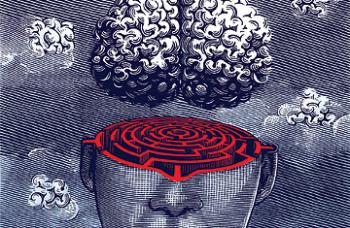

The Mayhem of our Minds

I was blown away by Zadie Smith when she came to Bryn Mawr in October. She spoke to us about death, a seemingly faraway yet haunting eventuality for us twenty-somethings. She was so regal and so honest and humble that it made me want to be her. I thought that because she was so versed in matters about death, inspiration, ambition, and the hoop-jumping of novel-writing, her book NW would blow my mind. I thought it was going to answer all the awfully grey and misty questions about humankind. I thought I would love Leah or Natalie/Keisha like I love Jay Gatsby from The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

I was blown away by Zadie Smith when she came to Bryn Mawr in October. She spoke to us about death, a seemingly faraway yet haunting eventuality for us twenty-somethings. She was so regal and so honest and humble that it made me want to be her. I thought that because she was so versed in matters about death, inspiration, ambition, and the hoop-jumping of novel-writing, her book NW would blow my mind. I thought it was going to answer all the awfully grey and misty questions about humankind. I thought I would love Leah or Natalie/Keisha like I love Jay Gatsby from The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

But NO. I severely disliked NW. It brain-breaking to read the thing. The plot arc was practically nonexistent, the characters were pitiful and exasperating, the language tried too hard to be obscure and metaphor-heavy, and the lack of agency was demotivating. Above all, it was so, so chaotic. Practically nothing makes sense. There’s a poem about apples right in the middle of an important scene. NW spat at every reason why I read fiction in the first place. I read to escape reality. I am very well aware of the misery and the poverty and the disgusting sides to humans, thanks. I need relief, not reminding. I go to fiction to find some sort of order to life. My favorite novel, The Great Gatsby, does an effortless job of telling me why the rich can be morally reprehensible, and why it can be unnerving to find out your perception of someone is different from reality. I believe that all things happen for a reason, as clichéd as it has become. In fiction, almost everything follows that rule. I find this very comforting, because it is hard to find reasons when truly awful things happen to us.

NW does the exact opposite of what I wanted it to do. It does not provide order; it creates chaos. Nothing happened for a reason. Felix’s death was painfully needless. It creates a grim mirror of our world and reminds me of all the horrors I sheepishly read about in the tabloids. My brain was sweating trying to read it instead of being soothed. I put the thing down with one question swirling around: Why does nothing make sense in this book?

Anne helped me get this thought process started. I think Smith is trying to recreate the mystery and chaos of our minds in NW. Even today, we have very little idea about what goes on in the deep recesses of our minds. We know considerably more than we did twenty years ago, but that knowledge is only surface-deep. Neuroscientists can pinpoint regions of our brain where a tumor is located. But beyond what they can see with the current technology, they can only carefully speculate on what is happening.

I don’t believe that we understand our own chaos either. If I understood my own mayhem, maybe I could have spotted it being recreated in NW. On page 83, where Leah is supposed to have fainted, a voice snarls at the reader with questions like “Did you hope for something else? Where you misinformed? Was there more to it than that?” To me, this sounds more like the lyrics to Pink Floyd’s Wish you Were Here. On page 64, when Leah is in some sort of clinic, she goes into a confusing reverie that ends with “In its way, a greater revelation than the confusing lectures on consciousness, on Descartes, on Berkeley. Ten nine eight..... It’s been two and a half hours!” I still find it difficult to understand what Smith is trying to accomplish here. So what if it’s been two and a half hours.

This mystery and bewilderment that dominates NW the best way to recreate our conscious selves trying to understand our subconscious. After all, for a man named Kevin, it got him into serious trouble with Homeland Security.

Podcast Radiolab’s producer Pat Walters reported on Kevin, a musician who has dealt with severe epilepsy since his teen years. In July 2006, after a seizure caused him to cause a serious car accident, he decided to get a brain surgery to remove the problematic area causing the seizures. The surgery was a success in that the epilepsy was gone. However, Kevin began to eat like a horse. He began to obsessively play a piano piece for nine hours at a time. His libido was racked up to eleven. What got him in trouble with Homeland Security was the stash of child pornography he began downloading. When his case came to trail, Kevin’s neurosurgeon saved him from five years of jail time. According to the neurosurgeon, Kevin has Klüver-Bucy syndrome. During his brain surgery, the surgeon’s accidentally removed a part of his brain that deals with keeping our morally unacceptable, most disgusting desires in check. Without this lid, Kevin could not neurologically control himself from downloading child porn and other reprehensible things. However, he consciously knew it was wrong and tried to fight it. When the neurosurgeon gave Kevin him a drug, “it was like flipping a switch” (quote from Kevin in the podcast). He could control those desires again.

Throughout the piece, Kevin asserted several times that he had no control, and no idea what he was doing. He says he knows himself. He would never endorse the sexual exploitation of children. What was so distressing was how he couldn’t understand why he kept doing it. Kevin’s story is not so different from that of the characters in NW. Felix doesn’t understand why he keeps gravitating towards his trashy ex-girlfriend for sex, Leah doesn’t “understand why she has this life” (399), and Natalie doesn’t understand why she doesn’t understand herself. It is because of this cacophony that NW is still taken seriously by me.