Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Stereotyping genres

In Chapter One of Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud writes of his youthful assumptions about comics; he "knew exactly what comics were. Comics were those bright, colorful magazines filled with bad art, stupid stories and guys in tights. [He] read real books, naturally" (pages 1-2, emphasis omitted). This genre snobbery -- the idea of "real books" and other, lesser forms of reading material struck me, and it came to mind during part of our discussion in class on Tuesday.

Romance novels popped up in this discussion when Anne mentioned Jeffrey Eugenides' The Marriage Plot and whether, in fact, this literary genre/storyline is still relevant today. I said that I think it is; after all, romance novels are one of the best-selling genres out there. Anne agreed that romance feeds a certain emotional requisite for some people. A few minutes later, she mentioned that romance novels may "fulfill emotional needs for someone who has just been divorced or can't find a partner."

Aha! I thought, writing it down in my notes. That's a stereotype. (And, I should add, one very widely-held, though untrue.)

I love romance novels. Not all of them, of course. I don't love all books in any genre. But, even though some romance novels suck, many are absolutely wonderful. Just as in any genre. I recently turned twenty-one. I'm not divorced, or a spinster, or emotionally unfulfilled. But I love to read love stories, and I love happy endings.

Still, I don't often mention my love of romances in academic circles. In fact, when I had my first conference with Anne, and she asked me what I liked to read, I intentionally omitted romance novels. I did not forget them. I considered mentioning how much I adore the genre. I had just come from the library, and so had the two books I'd checked out on me. Before approaching Anne for our conference, I stuck the one by Loretta Chase in my purse and kept the one by Umberto Eco out. (I'd have put it in my purse, too, had there been room, but I did not worry that Anne would judge me for having it, as I did with the romance novel.) In our subsequent conversation, I mentioned that I loved mysteries, like those by Agatha Christie, and speculative fiction, especially Neil Gaiman (so excited the read part of the Sandman series for a class!). Not mentioning romance was an act of cowardice, and rooted in genre stigmas.

Certain genres are looked down upon. Comics, mysteries, and speculative fiction are all derided as formulaic, escapist, and without literary worth. But, I think, romance suffers the worst of this stigma. People who read romance aren't just reading worthless escapist fantasies, they are doing it because they are women who couldn't get a man -- cat ladies who would rather live in books than in the real world, and who possibly can't tell fact from fiction. With this genre, I often meet people who don't just judge the books -- they judge the reader, too.

A recent article in The Awl argued, amongst other things, that "romance novels are feminist documents. They're written almost exclusively by women, for women, and are concerned with women: their relations in family, love and marriage, their place in society and the world, and their dreams for the future." This was suggested as part of the stigma against the genre, and I do think that there is a lot of truth in that. The genre is dominated by women.

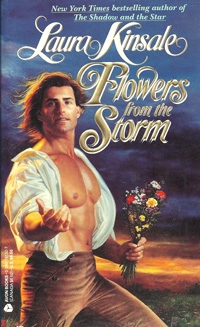

(That said, in discussing this stigma, it might be pertinent mention the stereotypical romance clinch cover. Much like the brightly-colored comic covers that a young McCloud looked down upon, the romance novel can wear a cover that all but begs for scorn and disrespect, while doing little to advertise the story within. Seriously, look at this cover, the original cover for Laura Kinsale's Flowers from the Storm, later reissued in less horrifying form. Are you not entertained scared out of your wits? Shiny Nightmare Torso Bad-Wig Fabio over there couldn't be more frightening if you dressed him as Pennywise from It. And you'd never guess the subjet matter, about a mathematician in the mid-19th century who suffers a cerebral hemorrhage that leaves him unable to speak, leading to his confinement in a lunatic asylum and subsequently to a romance with a devoutly Quaker nurse who knows he isn't crazy.... It's a long story. Literally -- almost 600 pages. But the cover doesn't help tell it. I can understand people assuming that books with such covers aren't very good.)

(That said, in discussing this stigma, it might be pertinent mention the stereotypical romance clinch cover. Much like the brightly-colored comic covers that a young McCloud looked down upon, the romance novel can wear a cover that all but begs for scorn and disrespect, while doing little to advertise the story within. Seriously, look at this cover, the original cover for Laura Kinsale's Flowers from the Storm, later reissued in less horrifying form. Are you not entertained scared out of your wits? Shiny Nightmare Torso Bad-Wig Fabio over there couldn't be more frightening if you dressed him as Pennywise from It. And you'd never guess the subjet matter, about a mathematician in the mid-19th century who suffers a cerebral hemorrhage that leaves him unable to speak, leading to his confinement in a lunatic asylum and subsequently to a romance with a devoutly Quaker nurse who knows he isn't crazy.... It's a long story. Literally -- almost 600 pages. But the cover doesn't help tell it. I can understand people assuming that books with such covers aren't very good.)

All of this has me thinking about the stigmas surrounding certain genres, judging books (including comic books) by their covers, and what that says about the future of genres. Comics/graphic novels seem to be gaining respect. Maus even won a Pulitzer. Will comics eventually be respected as evenly as non-graphic stories? Will other genres? What causes a genre to be respectable or not respectable?

ETA: In the course of writing this post I found an interview with Neil Gaiman from 1999, on a website about romance novels. In the interview, Gaiman talks some about comics, and related an interesting terminology anecdote, in which Gaiman "got talking to a guy who turned out to be the literary editor of the Sunday Telegraph. He asked what I did. When I answered that I write comic books, he looked at me as if I had confessed to shoplifting or something. So we're standing there having a drink and he's looking uncomfortable, but before I can walk away he asked what kind of comic books I write. When I answered they were the Sandman series, he looks at me, says, 'Hang on, I know you, you're Neil Gaiman. My dear fellow, you don't write comics, you write graphic novels.'

"So as far as I can tell, it's just a difference between being a hooker and a lady of the evening. Basically. The nice thing about calling them graphic novels is that people who can't quite cope with comic books can cope with them under the term 'graphic novels." So, for that editor, comics were a disreputable genre, but the same books called "graphic novels" were not.