Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Elementary Science Education as Conversation

Science as Interactive Conversation: Trying It Out In Elementary School Education

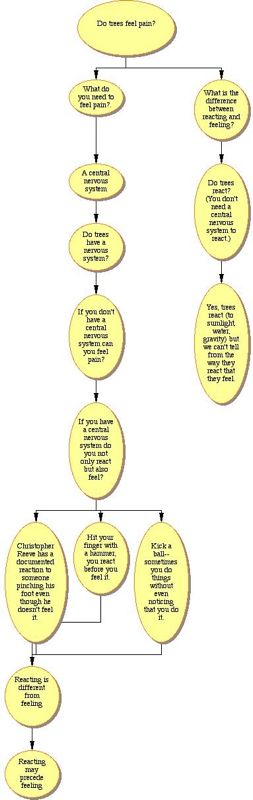

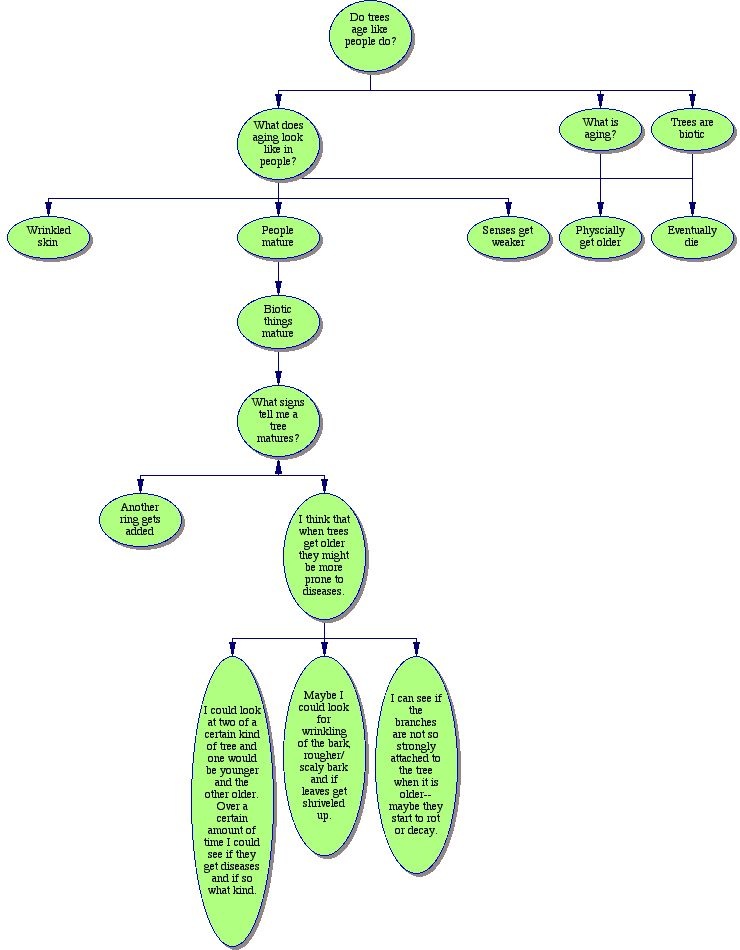

Can one sucessfully engage elementary schools students in science using an open-ended conversational approach, focusing on student curiosities and reflection on the issues they in turn generate instead of on the equipment and procedural details that often characterizes science education (and sets it apart from other educational activities)? Documented here is a class session aimed at exploring this question, organized and described by Deb Hazen. Included is a sample of concept trees created by students following the session. The visit was supported by a grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to Bryn Mawr College, and contributed to a school wide "inquiry day" during which students, teachers, and parents shared stories about science education.

On Thursday, October 1, 2008, Dr. Paul Grobstein visited the 5/6 classroom at Lansdowne Friends School to work with students as they explored what science is, how scientists work, and what it means to learn about and do science. Every student was engaged in an interactive discussion that stretched their understanding of their role as scientists and what it is that scientists do. Students also had an opportunity to share with Dr. Grobstein their reflections on what makes science education fun, engaging and helps them successfully negotiate new material.

The combined fifth/sixth grade class is populated by ten to twelve year old students. Students in this age band share some general characteristics. Ten year olds tend to be very good at memorizing facts. They like to sort, classify, and organize things and information. This is also an age group that likes to consider rules. Eleven year olds start to think more abstractly and begin to challenge adult explanations and their own assumptions about the world. Twelve year olds are enthusiastic about school work that they see as purposeful like research projects and work that they perceive as adult or grown up. In science classes at LFS we work to ensure that students secure certain content knowledge while teaching them to approach science as an inquiry, not a finite catalog of immutable facts established by someone else. This is challenging as we operate within a larger culture of the quick sound bite and instant access to a Wikipedia answer. Students at LFS also prepare for admissions testing to middle school that includes a lengthy standardized test. We guard against students developing a black or white, right or wrong, and please just tell me the answer attitude toward learning.

Having Dr. Grobstein visit and talk about science as a way to make more questions, giving us new answers (not final answers) to old questions that lead us new ways of thinking about things to address specific situations was eye opening for students. It is one thing for their elementary classroom teacher to say this is what scientists do. It is something very different for a working scientist to share this idea and give them examples from current work in the field.

Students also benefited from a simulation of exploring one of their science questions with Dr. Grobstein. They saw how it is much more interesting to look for evidence that initial thinking is wrong rather than setting out to prove a point. By walking through an example, they saw how when they find evidence that their original thinking was wrong they learn something new. Students were busy making connections between what Dr. Grobstein shared and their current understanding of the world.

One such connection led to an rather interesting exchange. The student

asked if a question in science is like an open number sentence in math.

This led to a discussion of how math is different because it is

essentially a game with rules created by people. Science on the other

hand is exploring without that set of human created rules; so while you

can know if you get a right or wrong answer in math, that is not the

case in science. The class with Dr. Grobstein's help next turned their

attention to student inquiry projects related to our study of the

ecology of the eastern deciduous forest. Dr. Grobstein was able to act

as a resource as students helped each other think about their self

designed inquiries and the directions their questions might take them.

This added to the excitement around this project.

The work that Dr. Grobstein did with our class will lead to greater depth in the inquiry projects. These inquiry projects will be presented to the wider community at a Saturday event at Lansdowne Friends School in October. I expect to see more students drawing connections between the way they test their world and science as a discipline and practice.

I also anticipate that students will be thinking about their reliance on internet search engines. Dr. Grobstein reminded students that when they find an answer on the internet, they should remember that they are reading what someone thinks after doing research or asking questions--the same questions that the students are asking. Students were reminded that the answers are always changing because people are always exploring. This is a profound thought for a group of students who can easily forget that just because you can find an answer on the internet it doesn't mean that the answer is authoritative or that we have all of the final answers to all of the questions.

Finally, it is my hope that students will share their experience with their parents and that a dialogue between parent, student and school will begin that explores the value to be found in balancing content based education with experiential education, specifically with inquiry science.

Comments

Post new comment