Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

And Tango Makes Three: Making Sense of the "Gay Penguin" Controversy

Note: I ended up having trouble putting the thoughts I had about this assignment into the form of a block of text directed at a single audience, largely because, as you will see, I found that there was not any one side I wanted to definitively take on these rather complicated issues. In the end, I think my audience remains mostly (rather prosaically) the other members of our class, but pay attention to how parts of my essay are directed at others, including the authors of Tango, parent Steve Walden, and scholar Joan Roughgarden.

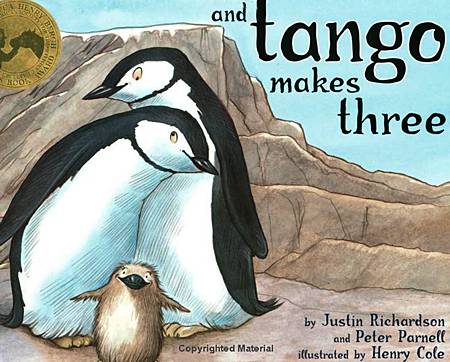

When you think of “banned books,” what comes to mind? Pornographic literature? A Mark Twain classic with problematic language? Maybe Judy Blume’s oh-so-brazen willingness to talk about teenage girls getting their periods? As I wandered through of my school’s library last week, I discovered a section of books about censorship. I’ve had an interest in the subject ever since the school board in my hometown, when I was in high school, actually banned a display in our school library celebrating banned books, on the grounds that it would make students ‘read for the wrong reasons.’ (I’m not kidding. Read about it here.) While I found references to all the usual suspects in my browsing (Catcher in the Rye, Harry Potter, etc.), I also found repeated mentions of a children’s book, published in 2005: And Tango Makes Three, by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell, illustrated by Henry Cole.

Based on a true story (the author’s note begins with the upfront statement: “All of the events in this story are true”), it explains how a zookeeper at the Central Park Zoo noticed two male penguins, Roy and Silo, were spending all their time together, including “bow[ing] to each other,” “s[inging] to each other,” “w[inding] their necks around each other,” and “build[ing[ a nest of stones for themselves…[where they] slept there together.” Concluding that, “They must be in love,” the zookeeper gave them an extra penguin egg and Roy and Silo ended up successfully raising a baby penguin (named Tango) together, following all the same parenting strategies the heterosexual penguin couples used. Near the end of the book, the authors make the statement that “Tango was the very first penguin in the zoo to have two daddies.” The book’s illustrations show not only the penguins and the zookeeper, but also a range of human families visiting the zoo, diverse in ages, genders, and races. Social conservatives have repeatedly challenged the book, on the grounds that it condones homosexuality and is therefore inappropriate for children. In fact, it was the most challenged book in America in 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2010 (briefly falling to second place in 2009), according to the American Library Association.

Steve Walden, a Christian man living in Colorado and homeschooling his children, published a blog post in 2005 about his experience with this book. He describes “unwittingly” checking out the book in a general search for information on penguins, and only realizing what it was actually about after his 6 year-old had already read it, after which he “spent an hour undoing the damage and it ruined not just storytime but the whole evening.” He describes exactly why he found And Tango Makes Three so problematic – and while I hesitate to let one person’s thoughts stand in for an entire sector of parents, I do think Walden elucidates quite clearly the central arguments of those who have challenged the story. He writes that, “This book made me angry because it forced a questionable sexual practice on my children, passing it off as something as legitimate as their own family. It attempts to normalize something clearly abnormal.” He directs his anger not just at the authors of the book but at those who choose to advance its message, explaining that, in his opinion, “this book has been insidiously and deceitfully placed in libraries across America to re-educate young children to accept all families as valid.” I think there are two important components to Walden’s argument here, the first being vaguely scientific: he finds homosexuality abnormal in animals as well as people, and doesn’t think the book has validity on those grounds. However, he’s also making a broader statement about the use of animal behavior to contribute to a debate about human behavior. I think he finds And Tango Makes Three rather sneaky in its collapsing of boundaries between nonhuman animals and humans, especially in light of his personal moral views about human sexuality. Both of these points deserve to be addressed.

To address the first concern, I would encourage Walden to familiarize himself with Joan Roughgarden’s Evolution’s Rainbow. Although I don’t expect him to incorporate it into his family’s curriculum anytime soon (in fact, the presence of the word “evolution” in the title probably marks it as exactly the type of text he is trying to protect them from), it might expand his ideas of what constitutes “normal” in the animal kingdom. Same-sex sexuality and parenting do occur in the wild, among many animals, even outside the artificial environment of the zoo. Roughgarden’s book reads like a laundry list of this and other types of sexual and gender diversity, full of such facts as, “By 1984 male homosexual behavior had been reported in sixty-three mammalian species” (137). One example particularly salient to this discussion comes in the chapter on same-sex sexuality. She explains, “Swans (Cyngus atratus) also form stable male-male pairs that last for many years. Gay swans may even raise offspring together as a couple. A female may temporarily associate with a male-male pair, mate with them, and leave her eggs with them. The male couple then parents the eggs and is reported to be more successful than a male-female couple because together they access better nesting sites and territories” (136). Even without a zookeeper replacing their rock with an egg, swan versions of Roy and Silo might have found each other, and this definitely undermines Walden’s argument that the story Richardson and Parnell put forth is scientifically abnormal. Roughgarden’s writing makes a compelling case that a false, heteronormative notion of normal dominates our scientific understandings of animal sexuality, and examples abound for recognizing diversity present in nature.

Walden’s second concern – that anthropomorphozising animals to contribute to a conversation about human morality is suspect – is actually, I must admit, one I kind of agree with. I think it’s possible to find fault both with the authors of Tango and Roughgarden herself on these grounds, even while I very much agree with their political orientation. Looking at the above example, Roughgarden’s emphasis on the parenting success of gay male swan couples is clearly meant as a response to social conservatives’ demonization of gay (human) parents. But looking at the reason for this success reveals gaps in the project of mapping animal behavior onto human behavior: males apparently have more power in swan society. Would the gay males’ swans parenting advantage diminish if feminist swans rose up and controlled more of the resources? There are limits to equating swan and human society. Tango is quite clear in its assertion that animal families and the human families who observe them at the zoo are similar in their diversity. But what if Roy and Silo turned out NOT to be gay, after all – would we then be forced to question the legitimacy of human homosexuality? We ought not to allow important questions of human morality to hinge upon the behavior of penguins or swans or any nonhuman creature. While humans are by no means immune from an evolutionary past, our decision-making abilities and moral compasses (though my own may be differ greatly from Walden’s) distinguish us from other animals and make efforts to use animal behavior to justify human behavior suspect from the start, regardless of the political ends they may serve.

As a final note, I want to say that there’s a difference between the long tradition of using animals as characters in fictional children’s books (Frog and Toad, Babaar, Winnie the Pooh) and using a story claiming a great degree of truth value to forward a political agenda. I would very much support children’s books modeling gay-parent families, even those using animal characters to do so, if those animals were merely characters. This type of children’s book could function as Frog and Toad's ponderings on friendship do – as important tools to foster dialogue about people, regardless of the fact that actual frogs and toads definitely do not conceptualize sociality as humans do. I think the effort to forward what seems to me to be a biological a statement about sexuality in nature and humans (a topic complicated enough to still be confusing to adults, as evidenced by the controversy surrounding Roughgarden’s book) via the venue of a children's book is fundamentally problematic, creating a product (Tango) subject to the worst kind of oversimplifying anthropomorphosizing. Why should we rest the (worthy!) argument for rights and acceptance for the gay community on such unnecessarily unstable ground?

Works Cited:

Richardson, Justin and Peter Parnell. And Tango Makes Three. Illus. Henry Cole. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005.

Walden, Steve. "And Tango Makes Three?" Dad @ Homeschool Blog. 5 October 2005. Accessed 31 October 2011 (http://homeschoolblogger.com/stevewalden/31086/).

Roughgarden, Joan. Evolution's Rainbow: Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People. 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Image: http://ncacblog.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/tango.jpg

Comments

Shared Precarity?

alice.in.wonderland—

So my first reaction is the realization that you’re creating a bit of a pattern here, that this paper, like your first, is about “the potential politics of literary efforts,” and “the effects they can have on readers and audiences.”

And my second is to realize that my thoughts—coming two weeks after you posted the essay—are now totally diffracted by the material we’ve encountered since. I’m actually hearing something of a conversation in my mind just now, as what you say provokes reactions among other writers we’ve been reading….

alice.in.wonderland: our decision-making abilities and moral compasses …distinguish us from other animals

John Humbach: Actually? “the whole drama of human life depends ... on the regularity with which the passions overcome reason …. People ... have no ... control over which things pop into their minds.”

alice.in.wonderland: We ought not to allow important questions of human morality to hinge upon the behavior of penguins or swans or any nonhuman creature…. Why should we rest the (worthy!) argument for rights and acceptance for the gay community on such unnecessarily unstable ground?

Karen Barad: Because “identity is undone @ the heart of matter itself” (consider the “queerness of the quantum”…).

(By writing this out as a dialogue I am of course encouraging you to keep on talking back!)

My third thought has to do w/ the best-working tonality and location for such a dialogue. One of the (many!) things I like about your paper is its rich range of reference—from that link to the outrageous story in The Daily News Record about banning a display of banned books, through all the other references to banned books, to the link to the Dad @ Homeschool blog.

But! given the location of your essay, which—like The Daily News Record and Dad @ Homeschool—is on the internet, there’s a funny sort of ‘talking past’ going on here; you say that you “would encourage Walden to familiarize himself with Joan Roughgarden’s Evolution’s Rainbow” (and also acknowledge that, given the title, he probably wouldn’t). So exactly who are you encouraging here? To whom are you speaking? Our class has read that book already, is familiar w/ its hetero-challenging statistics….

I admire so much of what you’ve done here, that I’m nudging you to take one more step: not talking about others, but speaking directly to—even with!?-- them. There’s been a lot of feminist theorizing about this step, of course. I’m thinking right now of what Elizabeth Spelman says in Inessential Woman, about the difference between imagining and perceiving another woman's life (the latter involves being prepared to receive new information, and adapt); between tolerating and welcoming someone's opinion (which means actively seeking out a serious critique of one's own viewpoint).

“Parts of my essay are directed @ others,” you say…but what might happen if you really did direct what you are saying to Steven Waldman, in the hopes of having a conversation, instead of “giving” him indirect advice in the covert form of a letter to your classmates? Judith Butler has been advising us this past week (here I go diffracting again…) that, since identity politics fails to provide a coalitional framework, we might consider “precarity as a site of alliance among antagonists”: “don't become concerned w/ the specificity of your own identity, when countering its effacement, but instead ask if you are acting for all.”

Is there any way you might apply such advice to building an alliance with Steven Waldman? Beginning not w/ your different political or religious views, but with your shared precarity as human beings?