Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Don’t Judge a Book by its Cover: a Comparative Reinforcement

Isabel Archer, protagonist of Henry James’ novel The Portrait of a Lady, is “guided in a selection chiefly by the frontspiece” when looking for reading material (The Portrait of a Lady 23).

After one of our class discussions, I found myself intrigued by the different editions of Henry James’ The Portrait of a Lady—I was fascinated by the different covers chosen to represent his novel. I decided to explore the different edition “frontspieces” in my essay, and, where possible, to include the back cover blurb. After finding my eighteen covers, I realized the blurb would also emphasize different aspects and/or themes of the novel, and perhaps complement the cover choice, so I scrounged them up. The women on the covers are in a variety of attitudes, with no dominant pattern among them; most often the cover features a solitary woman, yet there are several exceptions. Only a handful of the cover images are photographs—the others are drawings or paintings. Once I finished finding and comparing the eighteen covers, I came to a conclusion (and by extension, answered a critical question). My critical question, I decided, was this: can an image or blurb do justice to represent James’ 600+ pages of prose? And, could an image or blurb justly represent any literary work? My conclusion, after seeing these covers, was no. Each of the covers and blurbs highlights pieces of the book and leaves others unexplored. They are, truly, frontspieces.

And now, I give you eighteen frontspieces of The Portrait of a Lady.

Modern Library, 1945; an E. McKnight Kauffer book jacket design:

![]()

On this cover the portrait of the lady is overshadowed by her silhouette.

Wordsworth Editions:

![]()

Bantam Classics 1983:

“Capturing the grandeur of a gracious, splendid Europe of wealth and Old World sensibilities, this glorious, complex novel has become a touchstone for a great writer’s entire literary achievement. From the opening pages, when the high-spirited American girl Isabel Archer arrives at the English manor Gardencourt, James’s luminous, superbly crafted prose creates an atmosphere of intensity, expectation, and incomparable beauty.

Isabel, who has been taken abroad by an eccentric aunt to fulfill her potential, attracts the passions of a British aristocrat and a brash American, as well as the secret adoration of her invalid cousin, Ralph Touchett. But her vulnerability and innocence lead her not to love but to a fatal entrapment in intrigue, deception, and betrayal. This brilliant interior drama of the forming of a woman’s consciousness makes The Portrait of a Lady a masterpiece of James’s middle years.”

Penguin Classics 1984:

“The mere slim shade of an intelligent but presumptuous girl...a certain young woman affronting her destiny" is how Henry James describes his first perception of Isabel Archer, who grew into one of his most magnificent heroines. An American heiress newly arrived in Europe, Isabel does not look to a man to furnish her with her destiny; instead she desires, with grace and courage, to find it herself. Two eligible suitors approach her and are refused. She then becomes utterly captivated by the languid charms of Gilbert Osmond. To him, she represents a superior prize worth at least 70 thousand pounds; through him, she faces a tragic choice. The greatest of the novels of James's early period, PORTRAIT OF A LADY was deeply influenced by both Turgenev and George Eliot.”

Everyman’s Library 1991:

![]()

“The Portrait of a Lady is the most stunning achievement of Henry James's early period--in the 1860s and '70s when he was transforming himself from a talented young American into a resident of Europe, a citizen of the world, and one of the greatest novelists of modern times. A kind of delight at the success of this transformation informs every page of this masterpiece. Isabel Archer, a beautiful, intelligent, and headstrong American girl newly endowed with wealth and embarked in Europe on a treacherous journey to self-knowledge, is delineated with a magnificence that is at once casual and tense with force and insight. The characters with whom she is entangled--the good man and the evil one, between whom she wavers, and the mysterious witchlike woman with whom she must do battle--are each rendered with a virtuosity that suggests dazzling imaginative powers. And the scene painting--in England and Italy--provides a continuous visual pleasure while always remaining crucial to the larger drama.”

These last two covers feature women in a contemplative posture of decision.

Norton Critical Editions 1995:

“The text of this Second Edition of one of Henry James's most important novels is that of the New York Edition (1908). In a sense, there are two distinctly separate Portraits—the 1880-81 First Edition and the New York Edition, which James extensively revised. The editor has meticulously prepared a list of textual variants to facilitate comparative reading of the novel. Nina Baym, F. O. Matthiessen, and Anthony J. Mazzella provide differing interpretations of James's revision process.

Henry James and the Novel culls autobiographical excerpts from James's other writings—his Notebooks, the intentionally autobiographical A Small Boy and Others and Notes of a Son and Brother, and the travel books Italy Revisited, A Roman Holiday, and Roman Rides.

Contemporary Reviews and Criticism provides both chronological and critical perspective on The Portrait of a Lady. Four reviews from 1882 outline the novel's initial critical reception.

Seven important essays from the period 1954-1991 provide a wide range of critical responses by Dorothy Van Ghent, William H. Gass, Laurence B. Holland, Charles Feidelson, Louis Auchincloss, William Veeder, and Millicent Bell.

Bibliographical Aids includes judiciously selected secondary works on James from the wealth of material published yearly.”

A woman looking at herself (in a mirror) fittingly accompanies the critical edition.

1996:

![]()

The movie poster for Jane Campion’s The Portrait of a Lady is the only cover that visually places a distinct Isabel between other figures; here she is threatened by Merle and Osmond on both sides.

Oxford Paperbacks 1998:

“When Isabel Archer, a young American woman with looks, wit, and imagination, arrives in Europe, she sees the world as `a place of brightness, of free expression, of irresistible action'. She turns aside from suitors who offer her their wealth and devotion to follow her own path. But that way leads to disillusionment and a future as constricted as `a dark narrow alley with a dead wall at the end'. In a conclusion that is one of the most moving in modern fiction, Isabel makes her final choice. The Portrait of a Lady is the masterpiece of James's middle period, and Isabel is perhaps his most engaging central character. This edition provides a challenging new introduction and detailed notes; the text is that of the New York Edition and includes Henry James's own Preface.”

Wadsworth publishing 2001:

![]()

“By using the 1882 edition of The Portrait of a Lady, the text reflects more clearly the culture from and to which it was written. A significant number of fairly contemporary materials deal with etiquette/behavior, conceptions of the American girl and the American woman, discussions of Americans (especially girls/women) living abroad, and international marriages. Magazine and newspapers articles of the period help to set Isabel Archer in the context of discussions about national character, the American abroad, the American girl/woman, and so forth. The volume includes reprints of contemporary reviews, emphasizing those that found the ending of the novel perplexing.”

This cover has movement, with a woman in motion; it is not a still, traditional portrait. The blurb emphasizes Isabel’s “American-ness.”

Modern Library Classics 2002:

![]()

“One of the great heroines of American literature, Isabel Archer, journeys to Europe in order to, as Henry James writes in his 1908 Preface, “affront her destiny.” James began The Portrait of a Lady without a plot or subject, only the slim but provocative notion of a young woman taking control of her fate. The result is a richly imagined study of an American heiress who turns away her suitors in an effort to first establish—and then protect—her independence. But Isabel’s pursuit of spiritual freedom collapses when she meets the captivating Gilbert Osmond. ‘James’s formidable powers of observation, his stance as a kind of bachelor recorder of human doings in which he is not involved,’ writes Hortense Calisher, ‘make him a first-class documentarian, joining him to that great body of storytellers who amass what formal history cannot.’”

This cover’s portrait appears to be the visual and literal collapse “of Isabel’s pursuit of spiritual freedom,” it seems destiny got the upper hand on Isabel in this edition.

Penguin Classics 2003:

![]()

“‘I don’t want to begin life by marrying. There are other things a woman can do.’

When Isabel Archer, a beautiful, spirited American, is brought to Europe by her wealthy aunt, it is expected that she will soon marry. But Isabel, resolved to enjoy the freedom that her fortune has opened up and to determine her own fate, does not hesitate to turn down two eligible suitors. Then she finds herself irresistibly drawn to Gilbert Osmond. Charming and cultivated, Gilbert sees Isabel as a rich prize waiting to be taken. Beneath his veneer of civilized behavior, Isabel discovers cruelty and a stifling darkness. In this ‘portrait of a young woman affronting her destiny’, Henry James created one of his most magnificent heroines, and a story of intense poignancy.”

The incarnation of Isabel on this cover has a confrontational posture, and a direct, obstinate gaze; this Isabel would, on first glance, seem spirited.

Barnes and Noble Classics 2004:

![]()

“Widely regarded as Henry James’s greatest masterpiece, The Portrait of a Lady features one of the author’s most magnificent heroines: Isabel Archer, a beautiful, spirited American who becomes a victim of her provincialism during her travels in Europe.

As the story begins, Isabel, resolved to determine her own fate, has turned down two eligible suitors. Her cousin, who is dying of tuberculosis, secretly gives her an inheritance so that she can remain independent and fulfill a grand destiny, but the fortune only leads her to make a tragic choice and marry Gilbert Osmond, an American expatriate who lives in Florence. Outwardly charming and cultivated, but fundamentally cold and cruel, Osmond only brings heartbreak and ruin to Isabel’s life. Yet she survives as she begins to realize that true freedom means living with her choices and their consequences.

Richly complex and nearly aesthetically perfect, The Portrait of a Lady brilliantly portrays the clash between the innocence and exuberance of the New World and the corruption and wisdom of the Old.”

The scene in the cover painting is “charming and cultivated”, like Isabel’s initial impression of Osmond according to the blurb.

Dover Thrift Editions 2006:

![]()

“Young Isabel Archer, a beautiful American, travels to Europe where her naivete — and recent inheritance — attracts many suitors. But despite her great promise, she falls victim to her own provincialism. Exposing the differences between the New and the Old Worlds, James's masterpiece examines the themes of freedom, sexuality, and betrayal.”

This Isabel is not a looker, but her expression and posture are not too proper, giving her a rebellious, perhaps sultry, air.

Signet Classics 2007:

“The heroine of this powerful novel, often considered James’s greatest work, is the spirited young American Isabel Archer. Blessed by nature and fortune, she journeys to Europe to seek the full realization of her potential—or, in modern terms, to ‘find herself’—but what awaits her there may prove to be her undoing. During her journey, wooers vie for her attentions, including an English aristocrat, a perfect American gentleman, and a sensitive expatriate. But it is only after the ingénue falls prey to the schemes of an infinitely sophisticated older woman that her life takes on its true form. With its brilliant interplay of tensions and characters, The Portrait of a Lady is a timeless and essential American novel.”

“Isabel” isn’t even fully on the Signet Classics cover—it is the portrait of a fraction of a lady.

Blackstone Audiobooks 2007:

“An American heiress newly arrived in Europe, Isabel does not look to a man to furnish her with destiny; instead, she desires, with grace and courage, to find it herself. Two eligible suitors approach her and are refused. She then becomes utterly captivated by the languid charms of Gilbert Osmond.”

Pennsylvania State University 2008:

![]()

“The Portrait of a Lady is a novel by Henry James, first published as a serial in The Atlantic Monthly and Macmillan's Magazine in 1880-1881 and then as a book in 1881. It is the story of a spirited young American woman, Isabel Archer, who ‘affronts her destiny’ and finds it overwhelming. She inherits a large amount of money and subsequently becomes the victim of Machiavellian scheming by two American expatriates.

Like many of James' novels, it is set mostly in Europe, notably England and Italy. Generally regarded as the masterpiece of his early phase of writing, this novel reflects James's absorbing interest in the differences between the New World and the Old, often to the detriment of the former. It also treats in a profound way the themes of personal freedom, responsibility, betrayal, and sexuality.”

This cover has multiple figures arranged in a social atmosphere, and invokes societal portraiture rather than that of one lady.

Global Language Resources, Inc. E-book

![]()

“When Isabel Archer, a beautiful, spirited American, is brought to Europe by her wealthy Aunt Touchett, it is expected that she will soon marry. But Isabel, resolved to determine her own fate, does not hesitate to turn down two eligible suitors. She then finds herself irresistibly drawn to Gilbert Osmond, who, beneath his veneer of charm and cultivation, is cruelty itself. A story of intense poignancy, Isabel's tale of love and betrayal still resonates with modern audiences.”

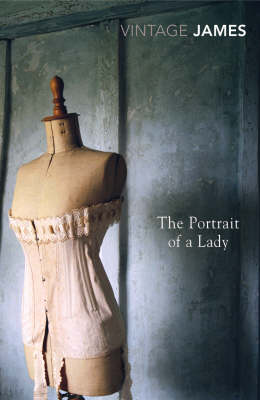

Vintage Classics 2008:

“Isabel Archer's main aim in life is to protect her independence. She is not interested in settling down and compromising her freedom for the sake of marriage. However, on a trip around Europe with her aunt, she finds herself captivated by the charming Gilbert Osmond, who is very interested in the idea of adding Isabel to his collection of beautiful artworks...”

My favorite cover is the last one, from the UK’s Vintage Classics 2008 edition. It features a form in a corset, implying women (at least in James’ day) are formed, and bounded by, restricted by, society (represented by the corset). Corsets are also part of the definition of a “lady”, and as they create the perfect form, women become objects to admire, like art. This cover emphasizes the degree to which Osmond thinks of Isabel as part of his collection.

Note: I organized the covers and blurbs chronologically to look for change over time, and I chose different mediums than only traditional book covers, such as an audiobook and a movie poster, to widen the field of comparison. Also, some of the editions’ dates of release are unknown.

Image and Blurb Credits (in order from top to bottom):

http://www.channelishop.com/Images/Products/Portrait_Of_A_La_499d1fa109eaa.jpg

http://www.randomhouse.com/images/dyn/cover/?source=9780553903973&height=300&maxwidth=170

http://i.biblio.com/z/237/432/9780140432237.jpg

http://www.randomhouse.com/catalog/winfit.pperl?pic_url=%2fcatalog%2fcovers_450%2f9780679405627.jpg

http://www.artexpertswebsite.com/pages/artists/artists_a-k/bunker/3.bunker.jpg

http://www.tbpcontrol.co.uk/TWS/CoverImages_01/019/283/0192833693.jpg

http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/41GPYAB569L.jpg

http://www.randomhouse.com/catalog/winfit.pperl?pic_url=%2fcatalog%2fcovers_450%2f9780375759192.jpg

http://a0.vox.com/6a00cdf3a56428cb8f00fae8ca6758000b-500pi

http://i.infopls.com/images/9780451530523.jpg

http://www.audible.co.uk/audiblewords/content/bk/blak/002436uk/t4_image.jpg

http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51SFZQJRDTL.jpg

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_nNV_LZph0Qg/R1BJcezQLmI/AAAAAAAAAaI/WUs3oKWGvTU/s1600-R/image001.jpg

http://www.waterstones.com/waterstonesweb/displayProductDetailsZoom.do?sku=6047513

Dedicated to Mom.

Comments

Seen from the Outside

Calamity--

what a treat to view this chronological line-up of the "frontispieces" of The Portrait of a Lady (in the various generic versions it has taken over the years). Like your last project, in which you made visual the "gaps" in The Diary of Alice James, you here highlight the non-textual: what we see (what is both covered and uncovered) when we look @ the cover of a book. I found myself much more intrigued by the visuals than by the blurbs, though the latter were also not lacking in interest!

I'd love to talk more with you about the aspects of James's novel that you feel are highlighted by this range of different covers--each one provokes a different reaction in me, and so seems to provoke a different conversation. That your "favorite" is a headless mannequin--what does that say about your own understanding of Isabel Archer, as lacking agency and individuality? That so many of the covers show an individual, alone: how much does that falsify the degree to which Isabel has clearly been shaped and formed by others (especially by Ralph)? Intriguing, for instance, that only the movie poster shows her caught between two schemers...while the novel covers seem largely to highlight her as solitary, in dazzling dress, but without any social context whatsoever: not even being viewed (except by us...)

If you were to shift your own p.o.v. from that a viewer of images to a maker of them, what sort of cover would you design for the novel? My own first thought was to highlight Isabel as seen from the inside, since this novel seems to circulate so insistently around her as its central consciousness:

(this is actually me, seen from the inside). My second thought is that it

might be even more striking to show Isabel whole body--and dress--

under a CAT scan (as has been done with Barbie, below):

Or maybe I'd do something even more abstract, like

the "flag of one's country, dishonored"*

(though I guess that's a spoiler. Hm...this is harder than it seems!)

*"Of course the danger of a high spirit was the danger of inconsistency -- the danger of keeping up the flag after the place has surrendered; a sort of behaviour so crooked as to be almost a dishonour to the flag" (The Portrait of a Lady, p. 54)

I guess my final reaction would be to ask you to "loop" back again to Isabel's selecting her reading matter based on the front matter. You are doing here exactly what she is (implicitly) criticized for doing @ the beginning of the novel. And so failing to read in the way James invites--indeed, according to jrlewis, instructs us--to: "The reader’s experience with the text parallels the protagonist’s story...." ?