|

Philosophy of Science 2006 Forum

|

|

Comments are posted in the order in which they are received,

with earlier postings appearing first below on this page.

To see the latest postings, click on "Go to last comment" below.

Go to last comment

Welcome

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2006-01-17 12:25:42

Link to this Comment: 17643 |

Welcome to the on-line forum for

Philosophy of Science at Bryn Mawr College, spring semester 2006. Like all

Serendip forums, this is a place for informal public conversation, a place to share thoughts and ideas in progress. What you're wondering and thinking now can help others with their thinking and what they're thinking can help you with yours. So don't worry about whether what you have to say is polished or final. The idea is to think together out loud and together, so everyone's ideas can help trigger further ideas in everyone else. Looking forward to seeing what we can make out of philosophy of science together.

Name: orah minde

Date: 2006-01-17 17:01:25

Link to this Comment: 17644 |

let's say that language, like philosophy, is "second order inquiry about first order practices" ((or, let's not say, and, rather, let's discuss)). the scientist is threatened by a philosophy of science bc such a philosophy takes the threatening omnisient stand-point. to be the object that is gazed upon is a vulnerable identity. such an outside standpoint supposes that there is an experience outside the experience of object from where the whole experience of the object can be viewed: an view that cannot be had by the object itself. scientists cannot, according to such logic, be philosophers of science. Similarly, according to such logic, a person cannot speak about himself. ((though this logic is obviously flawed, there is something to say for the idea that the Other has a better view of the self than the self has of itself.)) that does not sound quite right, so i'll phrase it differently: the scientist is not she who cannot be a philosopher of herself, but rather, the scientist is she who CHOOSES not to examine her work bc she finds the action of DOING her work sufficient. humm ...

let's discuss further the proposition that language is most basic to the academic sphere. academia, therefore, is the sphere of a second order inquiry no matter the discipline. the primary job of the academic scientist is to find findings and then, crucially, to inquire about his practice of finding through language. the first inquiry is private. the second, crucially, public. whether or not we regard the transcendent as internal or detached, can we say that this second level inquiry is a transcendent space? the private sphere for the non-academic scientist is sufficient. the difference between her and the academic scientist is the crucial space for the latter is not the private sphere, but rather, the classroom where people converge. a second order inquiry is, therefore, a public inquiry. we experience the world as individuals. all other experience is transcendent. if the transcendent is found internally than can we posit that the second level inquiry is crucial to what it means to be a human being. the existentialists would agree, no? they would say that the work of the private/non-academic scientist lacks meaning and only gains such in the public classroom. these ideas are not meaningful in my head, they only gain meaning here in the classroom or on the web. the web, therefore, can be seen as a transcendent realm. but it creates a new kind of public domain. while my thoughts are made meaningful/public here, we are secluded when in relation to them. i write them privately and you read them privately. so lets never give up on the classroom. enough for now.

misc.

Name: Laura Cyck

Date: 2006-01-20 10:11:46

Link to this Comment: 17698 |

Nothing to add, just a few thoughts... I read some of the exchange about

Storytelling & Story Telling and had to agree with most of what was said on the side of Story Telling. I got hung up on the idea of working towards a "more right" vs. a "more right" but never knowing "how right" vs. "less wrong". The 2nd seemed to be just as good as the latter since it seems to imply/require a continual improvement/exploration while never calling for there to be an end/final word. But since it nonetheless set some kind of benchmark, it was useful to take into account

two points on the side of "less wrong"-- that using a "less wrong" approach will be more productive in exploring changing and not only fixed systems and that while there cannot only be a number of viable "stories", all those stories may in fact be equally useful and able to account for the same observations/problems/etc. and impossible, at least for the moment, to “chose” between (not to chose as “right“ but to further explore). Now some things I'm confused/concerned about... Although storytelling supposedly has at it's heart the same commitment to an on-going exploration/improvement upon stories there still seems to be an element of an "end process" to it; viewing religion/ID/creationism as a competing story, as opposed to just a possible/maybe someday/not nearly has useful as evolution, leaves me with a feeling that storytelling is a process with an end while ID/religion will stand on the sideline and wait for evolution to lose and thereby win "by default", and then of course what happens after that? The reason behind teaching science as storytelling seems noble, but if I take the stand point of religion/ID/creationism I feel just as uncomfortable about the "rest of science"/other stories because even though with respect to story telling, religion/ID/creationism is allowed a fair shot and potential as a useful story at a later date if the story of evolution became less useful, religion/ID/creationism still takes a backseat nonetheless, so I don't see it as really stepping that much away from the issue. And one thing I was thinking about that was mentioned briefly on the first day of class-- Professor Krausz was talking about emergence and gave two examples. One being whether or not the shape of a bank of a river could be thought of an emergent property of the water molecules colliding with the bank, which seems like it could qualify as emergence. Another example was something about a friend coming to find you're not in your room because you came to class and whether or not that had some flavor of emergence, which I was confused about because my current understanding of

emergence thus far wouldn't consider this to be emergence, but rather just causality.

week 1

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2006-01-23 21:00:46

Link to this Comment: 17756 |

Glad others found our first session interesting/provocative. Agree that the

first order/second order distinction is an intriguing one to pursue further, am sure we'll get back to that as well as to both

story telling/storytelling and emergence as the course proceeds. In meanwhile, a few of the things that stick in my mind from our first session ...

Liked very much starting with the contrast between "an examination of the growth of scientific knowledge" and "an exploration of the nature of scientific knowledge", do think it sets up rather well a version of the realism/constructivism distinction in a way that usefully not issues that may not be so obvious. "Examination" certainly implies that there is something there "independent of interpretation" that can in principle be described. "Exploration" is more neutral on that point, and even I think on the question of whether the something would be altered by observing it (wish I had thought of a better word). It is a little wishy-washy as well on the question of whether one is necessarily interacting with something and particularly on the question of whether inquiry in fact creates something new. All of those SHOULD be looked at more closely, so I'm glad they were attributed to the word. The other point was "growt" versus "nature, highlighting the question of whether "progress" is an inherent part of the notion of science from a realistic perspective but not? from the constructivist. One could, alternatively, take this as a challenge (as I do). If one can't appeal to a "fact of the matter" and "correspondence theory" of truth/science, could one still define and claim "progress"? Would one want to? I think the answer is yes and yes. At least for me. To return to. And am intrigued by the issue of whether one could similarly argue for "progress" in literature, music, even religion?

Along which lines, am looking forward to further discussion of the political, and philosophical problem of how to adjudicate between different languages/frames, and deciding what to do with the "ineffable". If things look different in different frames/languages, and there is no preferred frame/single language, does one have to abandon any hope of adjudication? Might the "ineffable" be the extreme (ie singular) of distinctively framed (hence no words for it) and, if so, what significance should be accorded it in efforts to adjudicate?

Lots more to talk about. Thanks all for last week. Looking forward to this one.

week 2

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2006-01-24 16:45:41

Link to this Comment: 17773 |

A whirld wind tour through Popper but very generative. Thanks to all, including Orah, Laura, Michael for expert guidance. A few things that struck me, for my own records and whatever use they might be to others. Looking forward as well to hearing what others made of today.

Its important to recognize the context for Popper's work (as it is for all work), in this case the effort to correct some problems of "logical positivim" (itself a reaction to enthusiasms about things that "go beyond individual minds"). In this context (and still) the notion of an inability to verify universals and the recognition that one CAN "refute" is very powerful. "Conjecture and refutation" is I think indeed the core of "science" as methodology, noting not only its permanent incompleteness but also its dependence on "conjecture". And noting as well that while a scientific statement must be refutable, the motivation for one need not be.

Reactions to science as "uncertainty" rather than "certainty" brought up several additional probably misleading idea, one being the idea that something was non-scientific if falsified. Popper's position, as discussed, would have it that what is NOT science isn't falsified things but rather inherently unfalsifiable things (ie a marxism or psychoanalytic (or evolutionary or religious) posture that can turn any potentially falsifying observation into a supporting one). Its important here to distinguish "science" from motivation, eg marxism/psychonalysis/evolution may not be falsifiable but may motivate scientific statements that are.

Along these lines, an additionally interesting issue is the long term significance of motivational perspectives. If one of these leads to a falsifiable and falsified statement, that is sometimes taken as evidence that the perspective itself has been falsified, and probably shouldn't be. This relates to an additional misunderstanding about scientific methodology that Popper may not have given adequate attention to, the idea that progress occurs only in the present or, to put it differently, that new falsifiable statements can reliably be derived from older ones. In at least some cases, one finds that a new observation (or a new idea) not only falsifies present falsifiable though not yet tested statements but undermines or reduces the "usefulness" of earlier ones as well. In these cases, one may well "back up" and discover a new "generativity" in motivational perspectives that one might have thought have gone by the board.

Hmmm, just realized I'm slipping here from Popper's criterion of "falsifiability" for a scientific statement to "generativity", an idea that hasn't yet come up in the course (but will) that I've been exploring elsewhere (see On Beyond Post-Modernism: Discriminating Stories and Science as Storytelling or Story Telling). And have been having some trouble with that might be corrected by talking about "generativity of falsifiable statement"?

Some equally interesting issues when we moved from "methodology" to "ontology", ie to what the method is being used on/for. We'll definitely return to the issue of whether observations are "mediated" and to the merits or lack thereof of Popper's realism/appeal to the correspondence theory of truth and its necessity (or lack thereof) for motivating and providing a definition of progress in science. What's new (for me) is the realization that Popper actually had a justification for his "realist" posture that bears an interesting similarity to the slighly discounted argument from social consensus that in turn became the Kuhnian ("constructivist") battle cry. As Popper says in "The Aim of Science" "falsifications ... teach us the unexpected ... they reassure us that, although our theories are made by ourselves, although they are our own inventions, they are none the less genuine assertions about the world; for they even clash with something we never made". I think one can in fact get a coherent picture of science, with something out there and with progress (carefully defined so as to not amount to an asympototic approach to truth, out of "clash" (and, more generally, "conflict").

To talk more about. Thanks again, all, for the generative conversation.

Role of intuition/creativity

Name: Laura Cyck

Date: 2006-01-30 23:34:39

Link to this Comment: 17890 |

I've been trying to make better sense of "intuition" and "creativity" and their role in

the method/practice of science (whatever it is/may be). As systematic or methodical, for lack of a better word, I first found Popper's idea of science, it seems they both find their way into Popper's ideas. Given, he acknowledges that the start of the entire process requires conceiving of an idea and no doubt requires imagination/creativity: "There is no such thing as a logical method of having new ideas, or a logical reconstruction of this process. My view may be expressed by saying that every discovery contains an 'irrational element', or a 'creative intuition.'" (pg. 134) But he still appeals to intuition and creativity as being involved to at least some extent in next process-- evaluating ideas and deciding where to go from there. I wholeheartedly agree that dogmatism serves a useful purpose in science, it may even be a necessary component of skepticism or a critical evaluation-- by which I mean to be "fair" or critical requires at least a temporary commitment to dogmatism or "suspension of disbelief" in order to fully evaluate any idea and gauge all of it's parts. He says, "Supersensitivty with respect to refuting criticism was just as dangerous: there is a legitimate place for dogmatism, though a very limited one... Only if we defend them can we learn all the different possibilities inherent in [a] theory." (pg. 126) Now, maybe coming from a different perspective and trying to "dogmatically" accept another view in order to understand it may not involve any element of intuition, those at least subscribing to the idea in question would rely on a sense of conviction. (Though on the other hand, dogmatism need not necessarily rest on intuition. I could intuitively "prefer" the story of evolution while still willingly put my beliefs in another story [religion] that provides me with things that the story of evolution cannot [need for meaning, place in the world, etc.], in which case I'd be placing the needs for certain things over any gut-feeling sense of what I would want to otherwise believe. But whatever the case, it seems like dogmatism usually implies intuition.) Granted he cautions a limited place for dogmatism, he also says of conjectures: "As always, science is conjecture. You have to conjecture when to stop defending a favorite theory, and when to try a new one." (pg. 126) This I think better illustrates what I'm trying to say... conjecturing, I hope, rests on intuition. Also, for him, as a realist, to allow all this, especially seems off. By trying to make a case for realism, it seems that by allowing a creative process into the equation, particularly at the beginning (conceiving an idea), any ideas are automatically shielded from reality, should it exit; all ideas are from the get-go "mediated." If there exists a truly inaccessible reality, this would be why these ideas can

"clash with something we've never made." But this doesn't seem distinguishable from what I understood Kuhn as arguing, just one “social consensus” clashing with a different larger/broader/“stronger” “social consensus”... but anyway, all this reminded me of one of the points that struck me reading

Science as Storytelling or Story Telling-- “humanity” of the process [of science]. An element of “humanity” seems key in coming up with more and more “stories”, but seems in opposition to using “generativity” as a criterion for evaluation (/deciding/distinguishing). “Generativity” seems useful for judging predictability, but being also rather “systematic” seems to detract from that bit of “humanity”/creativity/intuition in deciding which path to take or which idea to explore further. Finally, one last thing I thought I’d add my thoughts on... last class we talked about refutation/corroboration and science as continual problem-solving as both parts of a (good) theory of education. Right now these make the most sense as far as education is concerned and that in my school/experience, like others in the class, science was always approached with an expectation of finding one, right description and “explaining away” phenomena to ultimately leave a single, final uninteresting “answer.”

week 3

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2006-01-31 18:02:09

Link to this Comment: 17903 |

Rich (generative?) conversation today. Thanks all, particularly Spalding and Heather for thoughts on Kuhn. Again, we did a lot in a short time but seemed to me good groundwork to think/rethink both Popper and Kuhn further as we move along this semester. Looking forward to what struck others. In the meanwhile, what intrigued me ....

How dependent IS Kuhn in fact on a "cryptic" appeal to "reality"? And to a demarcation that includes the idea of science as "progressive", in contrast to, for example, art? Is Kuhn's picture ENTIRELY "local puzzle-solving" with NO "cumulative" character?

I was, for some reason, more struck this this time around by Kuhn's paralleling of science and evolution

- both move with no "external referent"

- both involve local "puzzle solving"

- both involve alternate periods of relative stasis and change

- both display substantial history dependence

- both use "non-essentialist" category definitions (Wittgenstein's "cluster concept"?)

And, was (obviously) very intrigued by Spalding's (and Orah's) argument that Kuhn's description of science could be used for religious inquiry as well (Howard Kee?). This suggests that religious inquiry (like science?) might be better off without not only the concept of "revelation" (from an outside source) but also the concept of "Truth" or "reality". And provides some interesting new ways to think about the existence of different religious traditions.

Along these lines, I was struck by the absence in an otherwise quite sophisticated characterization of the "inside" of science by Kuhn of a key element that has recently become apparent to me in a different context: the inclination of (at least some scientists) to "suspend judgement", to avoid "premature story telling". To avoid inhibiting "generativity"?

And was obviously very intrigued as well by the discussion of a "motivation" for doing science at all, which both Popper and Kuhn (we'll get back to the latter's legitimate concern about "elementary observations") seemed to feel was a problem that had to be resolved. IS interesting that trees and other things "evolve" without needing a reason/justification but that scientist's need a motivation/justification? Because they can "choose"?, ie they would do it anyhow if they avoided thinking about it but because they think they .... ?

A possible relation between the last two points has to do with the bipartite brain, which we'll talk about in a few weeks. Basically, one might argue that humans have a distinctive part of the brain that habitually tries to "make sense" of things and that its because of this part of the brain that people in general have trouble avoiding premature story telling AND need to have explicit justifications for their actions (even if they are would they would do in the absence of such justifications).

The "progress" issue has turned up in my neurobiology and behavior class. And the science/religion discussion I mentioned has both contributed to and benefited from this one. Maybe there is something to philosophy from/in the trenches?

bloomin' and buzzin' and Revelation

Name: orah minde

Date: 2006-01-31 20:57:33

Link to this Comment: 17904 |

thx all, heather, and spalding for today and thx paul for continued conversation.

some ideas on revelation and beyond :

revelation is according to random house: "1. something revealed, esp. something surprising and not known before. 2. God' disclosure of Himself to His creatures."

and according to my computer: "a surprising and previously unknown fact esp. one that is made known in a dramatic way. 2. the divine or supernatural disclosure to humans of something relating to human existence or the world."

it comes from the french "revelare" which is "to lay bare".

in order for something to be revealed there must be an initial covering, or separation, between that which is revealed and she to whom the revelation occurs. In order for god to reveal herself to her creatures there must be a prior moment in which she is veiled from human senses. in order for there to be scientific revelation there must be a prior moment in which something is unrealized. revelation depends on a fragmented world. without such fragmentation "there can only be, in William james's phrase, 'a bloomin' buzzin' confusion" (Kuhn, 113). According to Kuhn, paradigms provide a lens through which we can order and see the world. sight cannot be all-realizing, rather, in order to see somethings we must be blind to other things. Since we are not built able to see all, since we are not omnisient, we must accept that are vision will always be partially blind. If we accept that we are not all-seeing we can accept that revelation of things previously unseen is a part of the human experience. things are constantly being revealed to our sense. simultaneously things are always being hidden from our senses. the idea of revelation does not depend on a God-Outside-absolute Other, but it does depend on an acceptance that our perception of the world is parced into parts that are seen and parts that are unseen: that we cannot know all, and, therefore, through experience are always coming into contact with the unknown. we need not seek a Truth that ends inquiry, but we can seek the unveiling of things previously unseen. such a cosmology deals with space: inside and outside. scientific revelation depends on the inquiry of an inside-science-community into an outside-space. maybe, even, there are three spaces: there's the inside space of science, there's outside-science-society, and there's the Outside space (i.e. Nature, God, Whatever, Nothing) that humans experience. One may suggest that this last space does not exist, but there still must be a parcing in order for there to be 'a bloomin' buzzin' confusion.'

the most interesting definition of revelation to me is: "the divine or supernatural disclosure to humans of something relating to human existence or the world." while one might think of the requires religious referent to be God, this definition reverses this requirement: the referent for divine revelation is the human: divine revelation is therefore always "relating to human existence or the world." this is a very Here-oriented, Nature(al) theology. This usage of the word revelation contradict's Paul's usage of revelation as something that is fundamentally External. This definition of revelation reflects a desire of the revealer to be Internal to human experience: to unveil himself to the human, to put himself INTO relation with the human. the paradigm search of religion, here, is not for that which is unhuman, but rather, for that to which the divine is attracted, namely, human existence or the world. separation is not bad. without separation there is only 'bloomin' and buzzin'.' revelation occurs in a world in which things are always being unveiled: there is no final, apocalyptic revelation, no Truth, there are only truths, and mini-revelations.

hoping for more conversation. my best to all.

week 4

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2006-02-09 17:00:43

Link to this Comment: 18045 |

Thanks to Alex, all for a generative/rich/enjoyable conversation based on Kosso. As usual, a few thoughts it triggered in me, with hopes others will chime in with their own sense of what was/wasn't/should have been/shouldn't have been said.

A nice "frame" for the discussion was the issue of whether the traditional philosophical distinction between metaphysics and epistemology was itself a "reference frame" ("paradigm"?, "point of view"? "world view"? "language"?) that necessarily conditioned any conclusions one drew from the observations one was using. Was Kosso's "realistic realism" a consequence of the frame he set? ("circularity"?). Where would the argument go if one accepted his offer to be a "responsible epistemological anti-realist" who would thereby refuse to make any metaphysical claim? Note though that there are actually two pretty different choices available here: one is that there is no "world beyond our observation" (bordering on "pure" idealism, solipsism, projectionism) and the other (more acceptable, to me at least) is that there is no "objective world beyond our observation", ie no world which we can characterize in any terms more absolute than those made available by our observations/thoughts at any given time.

I find Kosso's basic effort, somewhat stripped of some of its philosophical baggage, quite appealing/useful. What he wants understood is that physics (science) actually DOES "surprise" and therefore can't in fact be totally made up from inside. Moreover, it tries to and DOES notice, with great subtlety, aspects of our observations/understandings that are context-dependent (frame-dependent), ie that result either from our perturbing the system we are trying to understand or that would be different if we looked at them differently, and can and DOES successfully correct for those. The sun DOES look like it goes around the earth, the earth DOES look flat, but if we notice and correct for our limited perspective (by making new observations) we get a less perspective/context/frame dependent understanding: we are on an earth much bigger than ourselves which in turn moves around the sun.

Notice though that "correct for" is a little overstated. There is a still less "perspective bound" description that would include the sun rotating around the galactic center, the galactic center moving ... etc etc. One can "correct for" only those aspects of perspective that one has noticed. Having done so, there is no easy assurance that there aren't further aspects of that kind of perspective yet to correct for and no assurance whatsoever that there aren't OTHER kinds of perspective limitation that one hasn't noticed at all. In fact, the very concept of "correct for" carries an implicit presumption of realism. Might one instead simply call this process one of seeking additional ways to look at/see things? without needing the presumption that one is approaching a singularity which would be perspective (frame) free?

All this is a relevant to (an important context/frame for) Kosso's second equally important point: physics is not about generalities but about particulars. Einstein's physics does NOT say that everything in relative. It says that motion is relative but that the speed of light is absolute. Similarly, physics does NOT say that everything is "indeterminate" or perturbed by an observation. It says that CERTAIN aspects of certain things (position and velocity, for example) cannot be independently measured without a measurement of the value of one influencing the value of the other. Momentum (the product of the two) is among many things that are quite determinate.

So far so good. But its here that I think Kosso verges uncomfortably close to Popper's achilles heel, a belief that there is an objectively describable reality and that falsification gets us closer to it. Physics has, can, and presumably will continue to surprise us by discovering that things we took as fixed/eternal/invariant are actually perspective/frame/context dependent (measurements of length and time, for example) and it will, each time it does it, establish that SOME things are not perspective/frame/context dependent. But, and its an important but, one can draw conclusions ONLY over the set of context/frame/perspective variations that have been explored SO FAR. Which includes presumptions about what is relevant and what is not. Newton's laws hold in a vacuum (treating friction as a perturbation) at low speeds and intermediate size scales. The speed of light is constant holds in a vacuum (it doesn't otherwise) in all inertial frames. Popper's own concern about the limitations of induction are relevant here: there is not, and cannot be, from scientific activity, absolutes. Science is capable ONLY of characterizing invariances across enumerated sets of frame/perspectives/contexts. Unless and until someone establishes that the set of possible frames/perspectives/contexts is itself enumerable, there can be no claim from science that anything is "absolute".

All of this takes us back, it seems to me to the Bohr quotation that Kosso began with: "Physics concerns what we can say about nature" and to responsible epistemological anti-realism. But with the understanding that the latter need not deny either the power of physics nor the existence of something "out there". Einstein may indeed have said "Physics is an attempt to grasp reality as it is thought independently of its being observed" but he also said "Physical concepts are free creations of the human mind, and are not, however it may seem, uniquely determined by the external world". My guess is that the only real difference between the two was that Bohr was less driven than Einstein by the unknown. Both knew there was no certain relationship between what they were understanding and "reality". Bohr was inclined to let it be so; Einstein regarded it as a source of energy for taking the next "less wrong" steps.

As, I hope, will we. Lots of the "rules" of physics/science (perhaps inquiry in general) have their origins in "realism", cryptic or otherwise. If we are going to deny the validity of that starting point, we'd better be prepared to come up with some replacements for those rules. Maybe that's our task for the rest of the semester? If so, maybe Theory and Practice of Non-Normal Inquiry (to which our conversations have contributed importantly) is relevant.

Reference Frames

Name: Heather

Date: 2006-02-09 22:55:14

Link to this Comment: 18049 |

Kosso does want to allow for our reference frames to be "corrected", but like Prof. Grobstein brings up, there could very well be observations that we haven't made yet that would correct the frame we have now. I guess the question is, as Prof. Grobstein also says, whether our new observations are really correcting anything or if they are just a different way to look at the same thing. I think we would need to posit a real world and some amount of access to it if we are to posit that our observations are corrected. Perhaps it really isn't necessary to have a frameless reference point, however, if our reference frames are useful for our present purposes. Spalding and I were arguing a similar point as Prof. Grobstein and Prof. Krausz in the last class, of whether human behavior can be explained fully through biology and culture, or whether there is something more than that, such as the source for human creativity. I thought that biology and culture is a useful reference frame for describing human behavior. However, Spalding brought up the point that if there is indeterminacy in matter, since humans are made of matter, there might be indeterminacy that is a part of our behavior that we cannot explain through biology and culture. Sort of relating to this, I had a question for Prof. Grobstein. If things like pens are in a state of both being there and not there until we look at them, would it then be the case that people are in a state of being both here and not here, but are here in virtue of the fact that we are conscious of ourselves?

indeterminacy, human and otherwise

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2006-02-10 08:59:41

Link to this Comment: 18051 |

Yep,

biology and culture aren't (to a biologist/neurobiologist at least) enough. See

From Genomes to Dreams and

Variability in Brain Function and Behavior. And that DOES, I think, bear in several potentially interesting/useful ways on our frame discussion.

It hadn't occurred to me that we are outselves "in a state of being both here and not here" that is resolved by consciousness into being here, but I like that idea a lot in connection with some earlier efforts to make sense of (and correct) Descartes. What had occurred to me is that the brain is indeed often in "indeterminate" states in more local way. Perhaps the simplest and most dramatic form of this has to do with ambiguous figures. What one sees for a given input is indeterminate until one part of the brain resolves it.

And that in turn bears in an interesting way on the question of whether there is a "real world". If the input is resolved one way, one sees one thing and acts one way. If the input is resolved a different way, one sees a different thing and acts in a different way. One is, of course, a part of the "world", so that, to a greater or lesser extent, the world is changed by how one acts, and that means the world is actually not a fixed thing but rather a thing which is continually changing in part at least as a result of how one sees it.

Ergo, the world is indeterminate because of our presence in it (among other things)? And science is changing because of our own changing patterns of inquiry?

Name: Laura Cyck

Date: 2006-02-11 22:49:46

Link to this Comment: 18070 |

Just some thinking out loud... One of the things I'm trying to make sense of is distinguishing between the three possibilities of 1) (anti-realist) there is no "out there" 2) (metaphysical realist) there is a "there", independent of/existing before us and is fixed/unchanging and 3) (metaphysical realist?) there is a "there", independent of/existing before us, yet changing or influenced and affected by our existence/activity in/with it (or maybe the fourth possibility of an external world with some things changeable others not... this is I guess what Kosso is describing?) My concern, I guess, assuming an "out there", is there a meaningful distinction between changing something and influencing something? The understanding I'm getting from realists is that the "out there" is really not as independent as it first seemed to be and not so static. The idea of something being indeterminate and in two states at once isn't easy to swallow. I keep thinking of the pen example from class-- if it is indeterminate and exists in both the state of not being there and being there, but then is observed and rendered as being in the latter state (?), what is it that is independent and what is it that is dependent (the experience of the thing or the thing itself?) Is then pen itself really being changed/influenced?... any help making better sense of this appreciated. Also, I forget if this was discussed in class or not, but Kosso's description of "objectivity" was interesting. I found it useful to think of being objective not as an aim to escape one's perspective (and reach Nagel's "view from nowhere") but to "understand our point of view" (and then presumably try out new ones). And on the difference between Bohr and Einstein and more generally between an epistemological anti-realist view and an epistemological/metaphysical view-- in Kosso's discussion of inference to the best explanation, his second argument for IBE is the psychological accomplishment, "an explanation is a claim that satisfies our curiosity, a claim that gives our questioning rest, at least momentarily". An epistemological anti-realist view doesn't seem to lead very far, appropriate I guess only for pragmatists, and robbed of satisfactions of these psychological accomplishments by virtue of it's defeatist qualities. So, I agree that it's best/most interesting to adopt Einstein's attitude if for not for any other reason then for "curiosity". It was also useful to note Kosso's first argument for IBE and the criteria for what explanation is best-- compatibility or complementary, suggesting these replace simplicity; this makes sense since the principle of parsimony may be less useful judged against the backdrop of an inevitable reference frame.

hmmm

Name: Laura C.

Date: 2006-02-13 13:53:32

Link to this Comment: 18098 |

Just some rethinking... on the first day of class, when Professor Krausz asked us what we considered our positions to be in regards to realism/constructivism, I believe I said anti-realist/maybe constructivism. But after reading Goodman's argument for constructivism (? or whatever it will be called), and not finding it very compelling/useful at all, I feel more comfortable with a realist approach (though, constructive realism, as discussed in the other reading seems like a reasonable "compromise"...). I think I was drawn to an anti-realist approach/constructivism (or perhaps pragmatism?) because it seemed more flexible to change/revision/inconclusiveness (?) & puts an emphasis on "usefulness" (maybe "utility" would be better). Though, I guess I've realized now that a realist approach (epistemological or metaphysical) in no way requires such rigidity to revision or one single approach (frame?), allows for more skepticism/uncertainty than I had originally thought, and embraces it's own form of usefulness (?) (instrumentalism?); by which I mean in the sense of useful to scientific inquiry versus humanity/society/etc./instrumentalism[?]). Anyway, don't know if that all makes much sense, that's just where I am right now... Looking forward to tomorrow's class.

?

Name: Laura Cyck

Date: 2006-02-14 16:30:03

Link to this Comment: 18117 |

After class today Professor Grobstein jokingly (?) asked Marya and I if we thought today's class had found an answer (to?). At this point, I'm not yet comfortable saying for sure what are the most relevant questions to be asking in the first place (frames? objectively escaping a frame? choosing between? an ultimate? science and art? and culture? human fabrications versus elemental objects? complete versus partial versus obscured reality/Truth? aims/goals/objectives? individual versus community reference frame? meta- yet not all encompassing frames? realism>constructivism>mysticism?), let alone what their answers may be... but it seems most others know what kind of answers they'd like to which kind of questions?

week 5

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2006-02-14 17:35:15

Link to this Comment: 18118 |

I'm getting a little hard pressed for adjectives to characterize our sessions, which seem to me to be getting progressively more enjoyable/rich generative. So, thanks to Spaulding for a clear and provocative coverage of Goodman and McKenna, and to everyone for ... what I hope we're all both pleased by and coming to expect. Here's some notes on what stuck in my mind, hoping others will chime in with their own thoughts.

We're clearly into "reference frames" and the issues the recognition of them pose. In particular, is there a viable "anti-foundationalist" position that allows some adjudication among coordinate frames? An interesting aspect of that occurred to me as I was thinking about Goodman's speeding problem. One usually thinks that the inclusion/appreciation of cultural influences makes things more "relative". In fact, in the speeding example, the "relativity" is inherent in the situation before one introduces any cultural factors, and the effect of the cultural factors is to make things more "real" (we agree to use the earth as a common reference frame). I wonder how general that inversion actually is? Relativity (frame dependence) is the norm, and the concept of the non-frame dependent "real" ("absolute") is in fact the cultural construction? See below for a counter-argument?

Goodman's picture of "no fact of the matter" is obviously useful/generative, both for its recognition of the general coordinate frame issue and for some ... holes? The argument that language necessarily falls short of providing a description of reality is fine but perhaps not general enough for "coordinate frames"? And is a little ambiguous as to whether it is an argument against a world "out there" or only against a world out there that has a unique linguistic description. The latter becomes particularly significant in Goodman's effort to distance from "mysticism" as well as "linguamorphism". Mysticism, in some terms, is similar to Goodman's position in being skeptical of language/rationality. What Goodman's seems to want to distance from is any assertion that there actually IS a "reality" out there that can be accessed in any form, including non-rational ways (the idea that there is would seem to make mysticism a forum of metaphysical realism). Here too, though, either no reality outside the self or something out there which is not describable would, it seems, do for his purposes. More interestingly, perhaps is the issue of the relation of Goodman's position to other forms of "mysticism", characterized more by a "can't talk, can't act, can't engage with" posture, one emphasizing appreciation of rather than causal interaction with an "ineffable".

Goodman's digression into art and cultural history also proved to be generative. Is there a way to speak of "esthetic value" independent of cultural frames? And without claiming the existence of a single preferred coordinate frame? The parallels to science and "truth"/"reality" seem quite direct. Clearly there are communities of practice that make coherent esthetic judgements as well as coherent scientific ones. Is there a way to make discriminations between communities of practice in either case in the absence of a metaphysical claim, ie the claim of a single preferred reference frame?

In the absence of a metaphysical claim, there can be no single preferred judgement. This does not however, preclude the possibility of making at least some relative judgements, so long as one retains the possibility of at least two equivalent most favored coordinate frames. If one adds the stipulation (yes, I don't trust democracy in inquiry; there needs to be a bill of rights) that the meta-coordinate frame one is using must also contain the seeds of its own destruction, perhaps one can indeed conceive ways to retain discrimination in the absence of any absolute claims of truth or esthetic quality. An interesting extension of this would be to conceive of such a process occuring not only in human communities of practice but also in ways that do not depend on human cultures and perhaps not on the existence of humans at all.

McKenna's sophisticated plain-Jane realism is a good foil for Goodman (and the anti-realism postures we seem for the most part to be evolving. It does though seriously suffer from the natural=essential, artificial=subject to interpretation dichotomy that isn't very well founded (living organisms, at least, cannot be defined essentially, as Darwin pointed out; more on this later from Dennett). On the other hand, there are appealing elements in McKenna. Is the "individual" a required starting point? How is one to account for the observation that there do in fact seem to be better and worser ways to "cut" nature (at the "joints" or otherwise)? And how is one to account for the observation that there does indeed seem to be some kind of gradient of how easy it is to come up with alternate interpretations as one goes from the very small to the larger, at least into the middle realm of sizes? Its here where the issue of whether things get more or less real as one adds cultural factors is worth thinking more about.

There was an interesting connection as well of McKenna to mysticism, in his wish to have something for his Poppy. And hence of McKenna to Popper and his concern about scientists not having any motivation to do anything without "reality" (see also the little monk in Brecht's Galileo). Is this another form of frame-dependence? That might be adjudicated in some appropriately structured metaframe that allows discriminations but admits of multiple at any given time preferred frames?

taking a go at McKenna's realism

Name: alex

Date: 2006-02-20 00:52:11

Link to this Comment: 18217 |

Hey everybody - thanks for posting your thoughts, I've been reading along and been intrigued by the ideas on revelation, indeterminacy in our being until perceived, and the issue of order without an absolute reference frame. So just wanted to say - great forum.

I was looking back over the reading from McKenna, and was struck by his argument for preserving realism from being nothing but linguistic conventions, which seems to me to be somewhat unsettling. It seeems similar to Wittgenstein's idea of objects being whatever agreed-upon familial resemblance - but how far does culture and our education really go in determining our experiences? As a defense against Goodman's provocative claim that we cannot make assertions of a world undescribed, I was wondering if McKenna's Plain Jane metaphysics will hold without any sort of absolute reference frame. Logical positivists seem to have absorbed relativity as being unproblematic for the assertion of universal laws, but surely Popper's much more guarded and adaptable realism falls less readily to criticism on account of cultural intentionality, and even all that aside, is more resilient to the insurpassable relativity of any given reference frame. But what about McKenna's appeal to our commonsense that I take is a "correspondence theory of truth" kind of argument - does that still recognize the determinacy of a given reference frame? Perhaps in protecting the "joints" of the natural world from layered intentionality, one necessarily imposes an unjustified (frame-dependent) view?

One of McKenna's key points seems to have been that individuality cannot have been constructed, because we cannot even conceive of a world of "da stuff" or whatever without differentia. Thus there must be certain objects independent of our calling them so, and there is no reason to assume that they gain their properties simply after we recognize them. This seems reasonable to me - I want to agree with him here. Still, I think - can we even talk about individuality as being part of the world out there and not as an aspect of OUR world. So maybe there are no properties that we can point to and say are 100% natural. But that doesn't seem to preclude or even weigh against realism at all...I find Popper's unembellished presentation of realism to be helpful. Just that it seems rather magical that our intentions truly determine the world such that truth cannot be found, at all. Truth may not be provable, and any given belief is always not-true but rather in a state of becoming true for us, when we check: but an internal truth can be assessed for the sake of investigating the parameters of the reference frame. And I think we can talk to one another about the truth of that frame, and that is the highest that we can go in the way of Truth. I see that I have moved near Goodman's camp here - well, as long as the possibility of finding facts remains open (not allowing anti-realism to foreclose anything) then why not be limited in what we can assert to language, intentionality in addition to relativity?

to footnote a few of Paul's id

Name: Orah Minde

Date: 2006-02-20 14:35:46

Link to this Comment: 18228 |

"

Relativity (frame dependence) is the norm, and the concept of the non-frame dependent "real" ("absolute") is in fact the cultural construction?" could one translate this as: in order to face a world without frame cultures construct ... God ... an absolute ... a metanarrative?

one might argue that there is a difference between metanarrative and absolute. namely, that the absolute does not necessarily have a function, but is because of its unchanging quality. while a metanarrative DOES have a function and if that function is uncalled for it relinquishes its absolutism. the metanarrative, therefore, might not be considered an absolute. But, i might argue that stories never cease. they are retold, and reshaped, and make take a form that is unrecognizable as an evolution from its original form, but, i think, every story is rooted. there are no spontaneous stories. just as minds, are not blank. there is something eternal about every story. could it be the word at the beginning? no. bc some stories aren't worded.

acknowledging this possible difference between the words, lets play the word game of using them interchangably. there are, i think, two ways of applying these cultural constructions to the world. One might require that such words maintain the function they had in the first context to which they were applied. In this sense the metanarrative not only contains the mind of the culture, but also time and space that are external to the human mind. this metanarrative attempts to transcend the mind by collapsing time, space, and ceasing change. this metanarrative, however, cannot be a metanarrative (?) for all, because some might recognize its failure to transcend its maker. The metanarrative can function as a swaddle to comfort the human mind, but it fails to pull time and space and change into itself. some human minds, therefore, recognizes the failure of this metanarrative to hold that which is external to the mind. what does one do with such a recognition? maybe write another metanarrative. this world, i realize, is a relative world without absolute. The other way, however, (lets change the word from metanarrative to:) God might be applied is as a frame for the mind : the mind sees the world and applies the story of God to the world. because the function of this metanarrative is not to restrict, but is malleable to the world, it is (more?) durable than the previous absolute?

I am interested in the human confrontation with chaos. I am writing my thesis on a play that is about this stand-off. while Paul seems to be suggesting that some confront chaos with meta-stories, I am interested in the confrontation of the human without story-protection. the play i am studying uses the metaphor of skin: "Show me the words that will reorder the world, or else keep silent. if a snake sheds his skin before a new skin is ready, naked he will be in the world, prey to the forces of chaos." THE question of the play is, 'how do people change?' when stories crumble do we have to wait for new ones to proceed, or, is there a kind of 'painful,' skinless, naked movement ever-forward? the previous quote demands silence in the face of chaos, unless one is to offer theory-clothing. but, at the end of the play, God is rejected. "HE isn't coming back ... if HE did come back you should SUE the bastard ... Sue the bastard for walking out. How dare HE." so, yes, Paul, let's say all metanarratives for cultural constructions ... can we imagine a culture that does NOT require such stories? kushner, my playwright, imagines such a place. we proceed with a certain 'painful progress,' without the swaddle-padding of big stoires. is this what it means for the human race to be getting old? or, at least, growing up?

while kushner and Paul (?) seem to ascribe to this painful, flayed progress, i am reminded of some thinkers upon which i am performing a (3rd?) level inquiry. walter benjamin (thesis phil. hist), fredrich nietzsche (geneology of morals), and freud (beyond the pleasure principle) provide images of humans (and an angel for benjamin) longing backwards. i am looking now at nietzsche's writing, "i saw the GREAT danger of mankind, its most sulime temptation and seduction to what? to nothingness? - in these very instincts i saw the beginning of the end, stability, the exhaustion that gazes backwards, the will turning against Life." humm ... kinda heart wrenching, no? and familiar in an uncanny way ... no? kushner's vision of naked progression is not happy, or comforting, but "even sick. i want to be alive ... i want more life. i can't help myself. i do. i've lived through such terrible times, and there are people who live through much much worse, but ... you see them living anyways." Neitzsche isn't so sure. when metanarratives fail and we are confronted with unending chaos, one might seek another story (like kushner) and another might seek ... nothing. neitzsche's, i think, is the darkest of the three germans. and, maybe becuase of his shading, the most haunting. do we call him a mystic? ascetic? suicidal? desirous of that which is beyond pleasure?

... and ... 'how, in your experience of life, do people change?'

'the horror. the horror.'

Name: orah minde

Date: 2006-02-22 18:46:06

Link to this Comment: 18295 |

how can we "flag"/drown "the core of the human condition" i.e. the problematic that as conscious beings we cannot move in the world without story ?!?!?!? someone chat with me about it here??!?!?!?!? here are some possible implications of this condition:i.e. OUR condition:

can we liken the act of storytelling to the creation of a metanarrative ? while i acknowledge the distinction between meta-narrative and supreme-narrative, i am going to continue to call attention to their similarities, their origination from the same genre, their common features. and as a digression, even before i start, i want to make an argument as to the great similarities between the two. the word "supreme" means, according to the random house dictionary, "1. highest in rank or authority 2. of the highest quality or degree, 3. greatest or extreme, 4. last or final." my argument pivots on the observation that 3 out of the 4 definitions allow that 'the supreme' is supreme only because others are not supreme. a 'supreme' story gains its supremecy on the less-than-supreme nature of all other told stories. the subscription to a 'supreme' story does not cease the production of stories, but rather, is a choise of the 'highest quality' lens through which to see the world. i acknowledge that the def. that totters me, however, is the last one: "4. last or final," but i will suggest that as conscious creatures who can only experience the world through story the only way to act, to function, is to act AS IF the supreme story is the last or final story. we are more complex than the trees bc of this consciousness; this heightened complexity can be characterized by our ability to hold diverging concepts within us. Our consciousness' must hold the acknowledgement that there is no such thing as an 'ultimate/absolute' story, but in order to act we must treat every theory into which we place our bodies as if we were never going to undress from it again. ... i am avoiding the notion of an absolute story.

on that note, i am going to continue to think through the metaphoric lens of stories as clothing or flesh, the supreme narrative as merely a narrative from which the wearer is disinclined to disrobe, while the meta-narrative is a clothing set for the day, a snake's temporary skin. if the conscious being cannot act in the world without story/metanarrative/clothing/skin then what is the difference between a person who chooses to change his clothing and one who doesn't? there is no way for a conscious being to experience naked-reality, so to speak ... so what are the differences between the experience of a person who chooses to tell many stories and one who tells only one? if changing stories allowed one a glimpse of the naked-world in the instant of change, then i would be inclined toward the changing my clothes more offen ... but THERE IS NO EXPERIENCE OF THE WORLD WITHOUT STORY. so, i ask, again, how do people change? there must be a moment when a part of a story disintegrates and a CRUCIAL moment before that part is replaced? or, do parts of stories not dissintegrate, but are, rather replaced without loosening their grip on our bodies and perceptions? not that i WANT to see the world naked. but i am interested in the question of how people change their stories and maintain protection. i am inclined to assert that there is a lot of pain in those moments of change that comes from a moment of fuller exposure to what we are protected from when wearing our skins thick. was neitzsche's desire to go back purely nostalgic, OR was it a pulling away from future horror?

there are changes, and then there are changes

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2006-02-22 20:39:43

Link to this Comment: 18298 |

Chat? Sure. So, let's agree that we are "avoiding the notion of an absolute story" (ie in the context of the wider course converation, there is no preferred reference frame, and no prospect of ever having one). Does one have "to act as AS IF the supreme story is the last or final story"? No, I don't think so. In order to act, one needs only to accept that the story one has is, for the moment, the best one one has. "

The key here is that depriving EVERYTHING of the status of FINAL "authority" gives one permission/room to (not actually paradoxically) make use of everything one has at any given time."

The problem, for me, with the "metaphoric lens of stories as clothing or flesh" is precisely that it implies that there is something to which one would be more fully exposed in the absence of story. But that conflicts with "there is no experience of the world without story", which I take as a second essential starting point for the present discussion. IF there is no "supreme" story/reference frame, and if there is no experience without story/reference frame, then whatever there is in the way of "pain in those moments of change" must have its origin in something other than an experience of the world "naked".

I don't at all doubt that there IS, for many people at many times, "pain in those moments of change" but only your particular interpretation of its origin. My guess, in fact, is that there ISN'T any single explanation, that just as some people experience change as pleasureable and others as painful, so too people who experience it as painful do so for different reasons.

And the same person may in fact react differently to change at different times in their lives. Change has certainly been quite pleasurable at times in my own and quite uncomfortable at others. Sometimes the discomfort has been associated with realizing that something I've relied on without thinking about it is becoming less sturdy, and the unpleasant feelings have something of the character of disorientation or dizziness or insecurity. Other times, I have had a fear that a story I could live with was changing into something that, for one reason or another, seemed very threatening. The unpleasant feelings in those cases ("future horror"?) were much more fear than dizziness.

Can one "change their stories and maintain protecton"? One can certainly try to, but I suspect the cost is always to put one at risk of fearing change, if for no other reason than it creates the frightening story of losing "protection". Maybe one is better off enjoying the potential for change inherent in whatever story one has at any given time, looking forward to seeing what it becomes next, and so experiencing change as the promising process of writing one's own story anew?

week 6

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2006-02-26 18:01:12

Link to this Comment: 18352 |

And on, in our now routine (?) rich/generative mode. Thanks to all, and to Alex particularly for a thoughtful guidance through Putnam and Hempel. Some thoughts about where I (in my reference frame) think we've gotten to, trusting that others will add what it looks like from their own ...

I'm very intrigued by our continuing return to the "what does realism buy one?" issue. Both in abstract terms and in quite concrete ones. If we equate "interpretation" with "reference frame", then could we argue that "interpretation" and "reference frame" are, like velocity, both always "relational", ie that an interpretation/reference frame is not a thing in itself but rather a relation between a particular observer and what is observed? If so, the concept of "reference frame" itself exists if and only if there is an "interpretation".

That might seem to get us into some very difficult waters. An interpretation exists if and only if there is an interpretation? and an interpreter? Now, THAT has a pretty circular feel to it, and, like all circularities makes one worry about whether the interpretation or the interpreter came first and whether one is going to get into an infinite regress of interpeters interpreting interpretations. Maybe THAT's the answer to what realism buys one; it avoids dizziness? It's all interpretations (of interpretations of ... ) also raises some practical questions about how one should teach science (where's the "facts"?) and some spiritual ones (chaos isn't the absence of a frame/interpretation but rather a particular frame/intepretation?). THINK we'll be able to handle all this without ... severe gastrointestional problems?, but ... we'll see.

Equally intriguing along the "what does realism buy one?" line (to me at least) was the "as if" proposition: does one need to behave "as if" one was a realist? Without it, there would be no frame, no "story", and hence no movement/progress? Popper notwithstanding, I still don't buy it. Trees (and biological evolution in general) "progress" without any semblence of a conception of "reality" or of a perspective/coordinate frame. Here William James seems to me more relevant. James argued compellingly (for me at least) that acting "as if" is important, in that it was capable of bringing into existence things that wouldn't otherwise come into existence. His point was not that you need "as if" for hope or to motivate action but rather that it provides a groundwork for creation of novelty. Notice that that doesn't in fact require a notion of "reality", and indeed that a notion of "reality" might even inhibit the creation of novelty. The upshot is that one can indeed value the "as if" capability without becoming a "realist". Maybe the difference between trees (lacking "as if" capability) and people (having it) could help us with building a platform from which the "interpretation/coordinate frame" problem would look less daunting?

In the meanwhile, Putnam seems to me to help us solidify an important distinction between someone who thinks there is something out there that in principle can be described by humans independent of a human perspective and someone who thinks there is something out there but that it cannot be so described. What this does (usefully, I think) is to put the emphasis in thinking about the "realist/constructivist" issue more on the nature of humans and less on whether there is or is not something beyond humans (ie out there). One can be a "constructivist" in the sense of asserting that any human description involves a human perspective without denying that there is probably something out there, in which case the "noumenal" does, as Putnam argues, become irrelevant. And yes, I personally would have been happier if Putnam had in fact opted for "pragmatic realism" instead of "internal realism". And happier still if he had termed it ... "pragmatic inside/outside transactionalism"?

What I had missed in Putnam but Alex appropriately picked up was a set of "moral" issues inherent in all this: "These thinkers [Quine, Goodman, Davidson] have been somewhat hesitant to forthrightly extend the same approach to our moral images of ourselves and the world. Yet what can giving up the spectator view in philosophy mean if we don't extend the pragmatic approach to the most indispensible "versions" of ourselves and our world that we possess?".

One route to these "moral" issues is the set of concerns Hempel addresses. If indeed there is no preferred reference frame and there is no human experience without a reference frame, how does one handle/adjudicate among multiple reference frames? Can we get beyond post-modernism or are we stuck there? Do we need "reality" for this or can we handle it within a "non-foundationalist" perspective that denies the existence of any single preferred reference frame/perspective? Stay tuned?

Enjoyed looking at peoples' papers. A few quotations that seemed to me worth highlighting (anonymously, since I haven't asked permission but happy to add names of those willing to be quoted or to remove quotations entirely if those quoted prefer) ....

- "The world ... does not need logical categories, so there is no reason it should adhere to them"

- "It is funny that it is mostly the educated community that questions our existence and really."

- "The mystic ... attempts to apprehend the world through experiences that do not project the self toward but, rather, open the self to the approaching movement of the world. The desire of the mystic is, therefore, not to capture the world but to be captured by the world"

- "During periods of normal science, science may be more or less local puzzle solving ... during periods of crisis when paradigms are brought into question ... paradigms are compared not just individually with nature but also with each other -- a puzzle in its own right".

brain model & reference frames

Name: Laura Cyck

Date: 2006-03-05 13:21:38

Link to this Comment: 18451 |

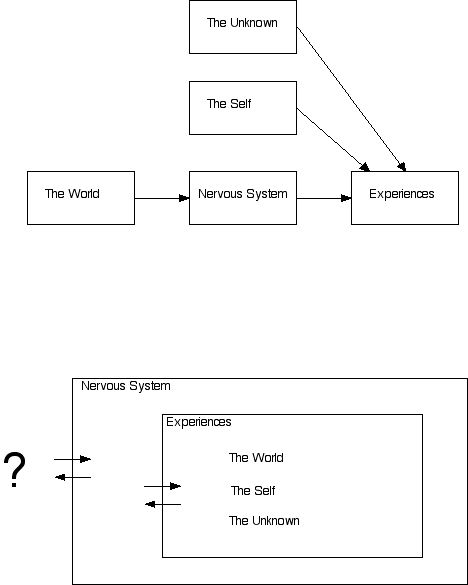

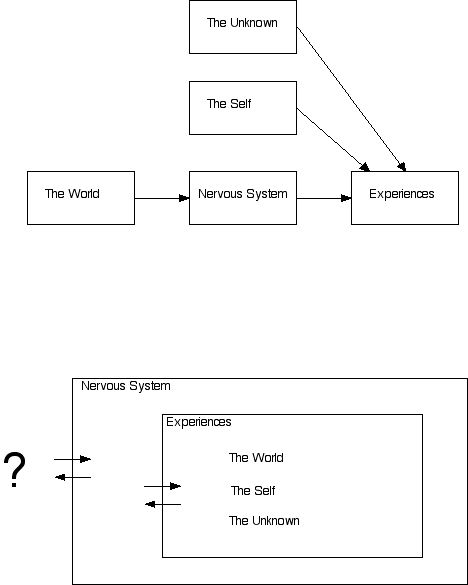

In last week's discussion of (pragmatic) multiplism, Professor Grobstein put on the board a similar diagram:

[x ] "ignorant"

[xxx] experienced/Emily's "advanced"/etc.; x's equaling observations.

Where these 'x's, or "observations", give rise to interpretations...

[ABC] all these interpretations A, B, C include even unfalsified ones (as I heard it)

[^ ^ ^] <-- use of reference frame to pick a hypothesis A, B, C etc.

[ x ]

(outside the brain, a *probable* external world giving rise to many (most?) x's, but not all... and possible things "made up"/added at the level of ABC)

And so, it was said that when a brain needs to take action in deciding between A, B, C from any given x, reference frames are used to pick a hypothesis-- the action is based on a reference frame. This then of course supports the claim that one cannot escape any/all reference frames to be reference frame free, at least if one wants to take action. Anyway we were using the terms 'observation' and 'interpretation' distinctly (observation- tacit processing/interpretation-"I-function"[?]) which I guess I was using synonymously. But I was thinking of reference frames coming into play before even "observations" were made:

[ABC] <-- maybe here again

[^ ^ ^]

[ x ] <-- use of reference frame here or

(conjectured outside) <-- use of reference frame here

...so that there would be many precursors to any particular x in the outside world but the reference frame would filter them so as to precondition ABC, etc. This is what I was thinking of when Kuhn emphasized the distinction between different scientists seeing something as something else rather than just merely interpreting it differently. The brain model seems much more flexible and seems to offer more of a conscious choice of reference frames, but with Kuhn any certain reference frame seemed more unescapable. But I guess with a brain model or tacit processing/I-function dichotomy there's no where else to put reference frames, and a biologist is committed to doing it this way.

Also, I've really liked the methodology of falsification up until now, since it does not seem to stand up to the argument of proceeding from different reference frames. Hempel's quotation of Popper, "[basic statements] have admittedly the character of dogmas, but only in so far as we may desist from justifying them...", is very compelling and relevant even if one is willing to except multiple interpretations, because presumably we're not accepting "all" but willing to accept more than one (?).

week 7

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2006-03-12 18:01:59

Link to this Comment: 18487 |

Now THAT was a little different. Is interesting to have the author of a text sitting in the room and available for the discussion. Thanks to all for giving the paper serious consideration. Particular thanks to Emily for guiding us through it, and for her critique, and to Michael for the kind of fully engaged critique that I hope the paper deserves and that, in any case, is essential for any effective process of "pragmatic multiplism". A few thoughts that have stuck with me about a richly generative conversation ....

A significant issue continues to be what is "reality" for? Emily's characterization of her own starting point as a "realistic realist, "going towards one goal" was a useful one in this regard, particularly when this singularist notion of a goal was contrasted by Emily with a co-existing multiplist notion of purpose. Objects may have a variety of purposes, dependent on the observer, but the observer ... has one goal/purpose? If so, then "reality" may be useful to support ... a singularist conception of oneself?

Emily (appropriately I thought) pointed to a relevant and significant "self-referentiality" in the paper, ie a frame (or context) dependence that was an important part of the argument of the paper, and that was explicitly acknowledged at the end of the paper. Perhaps her concern might be that the author of the paper was only able to make the arguments made by virtue of not having a singularist conception of self? And, more generally, that serious philosophical (academic work in general?) ought not to be (or appear to be?) individual frame specific?

Emily was also concerned about an indeterminacy theme that runs through the paper and illustrated that, perhaps significantly, from her own experience: "friends call me random but I can always backtrack ... everything has its basis". Here too the issue may be as much about individual singularism/multiplism as about the nature of the world (that which is interpreted). Are individuals "independently creative"? If not, they may differ from each other and so conceive different purposes both for themselves and for other things but they do so in a universe that has provides the "basis" for what they do and so is the foundational "real". If individuals are, on the other hand, independently creative then ... neither they not what they can influence has a fixed basis and "reality" is not only what one sees but also what one creates ... both for oneself and for others?

If I've gotten the story right, there is a very interesting example of a frame difference here. And the question, of course, becomes how to adjudicate it. Is there a "less wrong" perspective? And, if so, what would it take to reach it? Perhaps the path is one that "discourages arguing about interpretations, and encourages instead dialogue about what is similar and different both about observations and about how interpretations/stories are created from them". And perhaps, along these lines, some of Beyond "Simple" Agents and Environments might be relevant to the conversation (and the course)? We'll get to it in a few weeks. In the meanwhile ....

I've never responded formally to Michael's published critique of my paper, at least partly because the course and our conversations have been such a productive exchange that I never felt it necessary to go back to it. I am though pleased to have the chance to make explicit my responses to the critique as well as my appreciation for it.

"Ideality is a product of the brain and restricted to the brain ... In contrast, I urge that from the brain completing the information that is brought to it by the eye (or any of the senses), multiplism does not follow ... A world exists external to the brains engaged in interpretive practices ... As powerful as the brain is, it may just be incapable of 'seeing' a singularist position beyond itself".

I actually acknowledged in my paper that singularism was an "admissable interpretation" and that there could be "a singularist outcome to science, at which point it will cease to be a significant human activity". So we have no immediate logical disagreement here. I do, though, have reservations, as expressed in class, about whether there exist so far truly "singularist" cases in science. "that unsupported bodies drop at a rate of 32 feet per second squared" is not, for me, an instance of "singularly true". It is, given a particular frame (the notion of an "ideal situation", and "Ideality is a product of the brain and restricted to the brain"), a very good/useful summary of observations but that's as far as I'm comfortable going with it. The brain is, on my argument, not limited to being a "completing organ" (which already presumes there is something to complete). It is also a creating one (this relates closely to "independently creative" above).

"Grobstein runs together two claims. First is the 'idealist' claim of our inability to know a 'reality' beyond our perceptions ... Second is the claim ... that , for a would be world independent of our perceptions, given the neurological constraints of the brain, it cannot be singularly grasped ... While the second claim may be defensible ... the first is not".

That the world, because of the way the brain is organized, cannot be "singularly grasped" is the main point of the paper. I am not, so far as I know (or intend), making an "idealist" claim beyond that. Could there be ways that don't involve the brain "to know a 'reality' beyond our perceptions"? I don't know of any, but have equally no way to establish that they don't exist. IF the brain is the "sole inquirer" AND the brain works as I have outlined, THEN it seems likely there will always be (as there has always been) more than one way to make sense of our observations to date, and that how we make sense of them at any given time will always be context-dependent (and subject to "independently creative" acts).

Note that this is NOT a classic "idealist" position. There is no claim here that all that exists is ideas that the brain creates, nor that there is nothing outside the brain. The claim is only that there cannot be (or, more cautiously, that there is very unlikely ever to be) a single acceptable interpretation of what is (probably) out there ("IF the brain ... etc"). The "out there" is in fact an important part of the activity of the brain (the "summary of observations"). The inability to say what it is does, however, I think suffice for now (and for the foreseeable future) to justify my claim that one cannot "provide a sufficiently certain description of the thing being interpreted so as to say what is its relation to an interpretation of it".

"Grobstein's position has further difficulties ... takes the brain to be a material thing. He does not explicitly say that the material brain must also be a product of the brain, but the claim is entailed by his thesis. But then, how can a brain be a product of itself? And whose brain is it that produces the brain? And what is the status of materiality?"

I fully acknowledge the self-referentiality of the story presented (cf Being, Thinking, Story Telling: What It Is and How It Works, Reflectively and the risks associated with that (see From the story teller back to the I-function). My guess though is that self-referentiality is not only inevitable but has quite positive features to it, among which is to encourage "independent creativity" in oneself and others and, by so doing, to provide the new things out of which further inquiry proceeds. As for "materiality", that is, of course, a creation of the brain (of lots of brains) trying to make sense of their observations. It is NOT, any more than anything else is, a starting point or foundation (more below).

"Notice that Grobstein's negativist epistemology (with which I agree) is quite distinct from his world-as-pictured-by-the brain hypothesis ... He rules out the realist account of falsity in terms of non-correspondence between propositions and the way the world is ... So an alternate account of falsity is required. But he does not provide one. The claim that "the world" is a product of the brain and is limited to the brain precludes the conceptual space required for criticism of the contents of hypotheses about the world ... also precludes the possibility of giving a coherent account of the aims of cognitive inquiry ... provides no conceptual space to ask such normative questions as to why you should pursue astronomy over astrology ... If such issues are settled exclusively in terms of the products of the brain, then normative questions cannot even arise"

The negative epistemology and the "world-as-pictured ..." are, for me at least, inextricably connected. As above, the latter seems to me to give rise to the former (though I will freely admit that it is possible that both in turn derive from something else). That said, I freely and happily admit that the paper falls short of "an alternate account of falsity", fails to provide "a coherent account of the aims of cognitive inquiry", and seems to provide no space for "normative questions". The paper was in an important sense a "deck clearing", written with the hope(?) that by forestalling some questions in order to explore others one might be in a position to take a fresh look at some of those postponed. I don't think I could then but think I can now begin to provide "an alternate account of falsity", a new account of the "aims of cognitive inquiry", and even a useful space for exploring "normative questions".

Quite relevant to all of this is a question Laura put during our last meeting and then expanded on in a

forum posting. That in turn motivated me to try and create a