Remote Ready Biology Learning Activities has 50 remote-ready activities, which work for either your classroom or remote teaching.

Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

|

A Conversation About Proprioception, the "I-function", Body Art, and ... Story Telling? |

|

|

I have tried to find other references to the relationship between proprioception and this term - "I-Function" ... Kristine Stiles (KS), 16 October 2005

I coined the term "I-function" for what I still think were some very good reasons but for some equally good subsequent ones I've tended to more recently use the term "story teller" in its stead ... Curious to hear more about your interest in this subject ... Paul Grobstein (PG), 16 October 2005 I wanted to use the idea of "I-Function" because it is descriptive of proprioception as an aspect of what happens in Body Art ... Kristine Stiles, 16 October 2005 [putting some of this] on the web would document your contribution to the development of ideas in neurobiology in the same sense that reference to me and the student papers in your essay would show some impact of neurobiology on art history ... I'm intrigued as well by the interdisciplinary and trans-platform (traditional and web publishing) aspects of a joint project of this kind, and would be pleased if you were as well ... Paul Grobstein, 22 October 2005 As for posting aspects of our dialogue on serendip, I would be honored ... The idea that art, art history, and neurobiology have something to say to one another is marvelous and certainly most welcome in the interdisciplinary climate of Duke, as well as, I suspect, Bryn Mawr ... Kristine Stiles, 22 October 2005

Follow the continuing dialogue excerpted from an ongoing email exchange

|

I read a paper by one of your students - Eliza Windsor - online entitled "The I-function and Alzheimer's Disease: Where is the Person?" The article was particularly intriguing regarding proprioception and the notion of the "I-Function." I have tried to find other references to the relationship between proprioception and this term - "I-Function" - but her only footnote is to a lecture that you gave at Bryn Mawr. Is this a concept that you developed, or does it come from psychology? Could you please suggest a source for further reading?

|

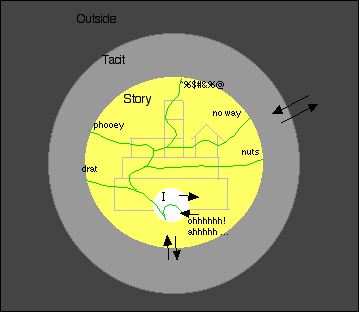

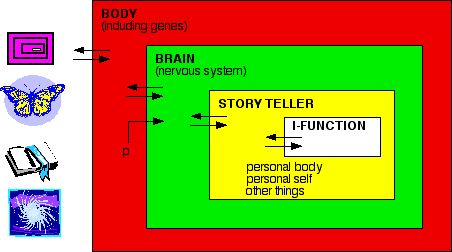

PG to KS, 16 October 2005 Thanks for your interest. I'm afraid you would indeed have trouble finding other references to the "I-function". Its an idiosyncratic term that I developed in the course of teaching and have used for a number of years. There are a number of references to it on our Serendip website but the only "traditional" publication in which I'm sure it is used is a chapter of mine in a collection of philosophy essays. A version of that essay is available on Serendip. I coined the term "I-function" for what I still think were some very good reasons but for some equally good subsequent ones I've tended to more recently use the term "story teller" in its stead (cf an essay on psychotherapy and the brain and a conversation on the brain and literature). In both contexts, what is being referred to is those aspects of brain function that support/create "consciousness" (as opposed to the much larger sphere of brain function that supports behavior without consciousness). In this regard, what's interesting about proprioception (to me at least) is that it represents an enormous and continual barrage of incoming information that greatly influences our behavior but that we (the I-function/story teller) has little or no direct access to. Curious to hear more about your interest in this subject and happy to help if I can with additional less idiosyncratic references. There is some nice older stuff on the relation between proprioceptive input and consciousness, and probably some newer stuff too.

|

Thanks so very much for getting back to me so quickly. I did consult all your students' papers on the web at Serendip and realized that it must be something you were developing, which is why I wrote to you. I wanted to use the idea of "I-Function" because it is absolutely descriptive of proprioception as an aspect of what happens in Body Art (both in terms of the viewer and the artist). I will excerpt a section of an essay I am writing on the very well-known (well, infamous) performance artist Chris Burden. I'd love to have your thoughts.

|

PG to KS, 20 October 2005

I enjoyed reading your essay, agree that there is indeed an interesting "brain" issue here, and understand much better the source of your interest in the notions of "proprioception" and the "I-function". All that in turn encouraged me to try and clarify in my own mind a set of related issues. Which unfortunately puts me at risk of the proverbial "I never ask him questions because he always tells me more than I want to hear" problem. I'll trust you to winnow to what is useful to you, ask further questions should there not be enough on particular points, and redirect based on your own perspectives and understandings so I can continue to learn from your work too.

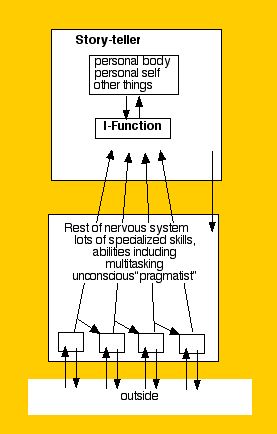

Since the "I-function" is my own neologism, I can legitimately claim that it means what I want it to mean. Which, however, doesn't mean the meaning mightn't change over time. Nor, of course, that I shouldn't be as clear as possible about what I actually mean by it (at any given time at least). The term originated in my mind from a set of observations to the effect that people with certain forms of brain damage were able, under certain circumstances, to point to objects in the world that they reported themselves being unable to see ("blindsight"). My inference was that what was damaged in such cases related to the particular and specific capability of saying "I saw that" while sparing an underlying and more general capability of acquiring and acting on information about things in the world. Hence, a disturbed "I-function", and an operational distinction between two kinds of brain function that corresponds roughly to "unconscious" and "conscious" processing (terms I chose not to use because they carry all sorts of ancillary baggage). Related phenomena occur in all sensory modalities, and don't at all depend on brain damage (we get and act on lots of sensory input without noticing either). An important further insight into them derives from some additional particularities of brain organization. All incoming sensory information goes first to the "unconscious" part of the nervous system and only subsequently and after processing there does it reach the "I-function". The important point here is that our conscious experience is necessarily and always an interpretation of signals received from the unconscious; we (our I-functions) have no direct information about what is "out there". What we experience (and hence what we are capable of reporting to others through the "I-function") is inevitably an interpretation involving prior processes in the nervous system of which we are unaware (and hence what we experience, and in some cases report, might in principle always be experienced/reported in some other way).

In recent years, I've tended to replace the term "I-function" with the term "story teller". In part, this is to give increased emphasis to the point that the interpretation "might in principle always be ... other", ie that there is an arbitrariness, and potentially a creative/discretionary element, inherent in the process that produces what we are aware of. In addition, it has become clear to me that not all awarenesses are centered around "I"; the story may be one not of "self", as it often is for many of us in modern western culture, but can also be about ... communities or other less individualized, egocentric actors. Thirdly, the original I-function concept seemed to make the process equivalent to verbal report/language usage, and it is clearly not. It is a process on which language depends but one that exists prior to language (see Polanyi on "Tacit Knowledge"). Perhaps most importantly, in the context of your interests, the story (our awareness, what we experience and are capable of reporting to others) is not actually as tightly bound to what one sees (ie to signals received from things "out there") as one tends to presume (and is implied by the original motivations of the term "I-function"). There is a substantial capacity of the nervous system to generate signals inside itself and these can/do play a substantial role in generating the signals from the unconscious that are the grist from which what we experience arises Hence, what I originally thought of as the "I-function" I now usually write/talk about as the "story teller", referring to a subset of brain activity that has the properties described (including the originally focused on ability to support "I saw that") but may also to varying degrees be relatively independent of sensory input.

Proprioception" is, of course, not my neologism and, like all commonly used terms, has a variety of meanings. None of them are co-extensive with what I mean by I-function/story teller (nor, I suspect, are they actually quite what you are reaching for) but many of them intersect with both in interesting ways that I think are quite relevant to your concerns. In its most general sense, which I think is the one you are partly (but not completely) interested in,"proprioception" refers to one's sense of one's own body as opposed to one's sense of things outside oneself ("exteroreception"). This distinction is a little muddy in some ways (is the sense of being upside down a sense of one's body alone or a sense of one's body in relation to something outside?) but useful in others (the sense of one's arm as being perpendicular to one's body as opposed to being parallel to it; the sense of one's knee as bent or straight, etc etc). Perhaps the most important use of the distinction is that it calls attention to a large class of inputs to the nervous system which tend otherwise to be ignored: the inputs from "proprioceptors", a very large group of sensory neurons that are designed (by evolution of course) to report to the nervous system information about the state of muscles, joints, and other body parts (in contrast to "exteroreceptors" that have evolved more to report information on things outside the body; these include those of the eye, ear, nose, etc etc). Here too, there is some fuzzy ground (the eyes, a classic "exteroreceptive" system turn out to play a major role in "proprioception"; this is why one can get dizzy in a movie theater), but also some usefulness in the distinction. To a not bad first approximation, proprioceptors provide the input that influences proprioception and exteroreceptors provide the input that influences exteroreception. And what's interesting (and I hope relevant) about that is that what I said earlier about "seeing" (and other examples of exteroception) is even more so for propriception.

By and large, activation of exteroreceptors is associated with an internal experience that, among other things, includes an association with the particular kind of exteroreceptors activated ("seeing" is different from smelling, tasting, hearing, etc). To put it differently, in the case of exteroreceptors the I-function/story teller gets from the unconscious (which, as you'll remember, is where all sensory signals go originally) some indication of the origin of the signals it has processed to generate the signals it sends on to the story teller. For proprioceptive signals these seems largely to be not so. In fact, for most people at most times, proprioceptive signals provide a perfect parallel in the intact nervous system to the phenomena of blindsight mentioned above. The signals play an enormous role in our behavior but we (our I-function/story tellers) are for the most part oblivious to their existence (this is the origin of the notion of "five senses", which persists in most textbooks despite the modern understanding that proprioception is a major input path to the nervous system). We may know (have the experience/story) that we are upside down but we have no information about how we know that. Its for this reason that "proprioception" is sometimes referred to as "body knowledge", with the implication that it is somehow outside of or otherwise different from what goes on in the brain/nervous system. It isn't actually outside the nervous system nor is it in fact qualitatively different from exteroreception in its engagement with the unconscious. Our sense of what is outside ourselves as well as of our own bodies are equally rooted in processing occurring within the unconscious. The difference between the two has to do instead with the nature of the signals sent from there to the I-function/story teller (and, probably, vice versa). There is lots of information about the body that is being used by the unconscious to control behavior without it being transmitted to the I-function/story teller in any form that makes it apparent in the story as a distinct kind of information. Without our being "conscious" of it. To say though that "proprioception" itself is "unconscious" (as many textooks and dictionaries do) is, however, seriously misleading. Just as it would be misleading to say that seeing is conscious. We may reposition our arm relative to our body without being aware of it but we may also have a clear experience of repositioning our arm relative to our body. Just as we may point to a visual input without being aware of it OR have an experience of doing so. Both exteroreception AND proprioception may but need not play a role in the story which is conscious experience. The only difference is that the story teller seems to have (or thinks it has) a little more information about what signals the unconscious got in the exteroreceptive case than it does in the proprioceptive case. What makes this all worth wading through I hope (for you; for my part, it has already helped me to sort some things out I needed to sort out) is that it establishes that there is not a simple one to one relationship between "proprioception" and "I-function/story teller" (which both the existing term and my older neologism perhaps might have been heard as suggesting). There are interesting differences between one's sense of one's own body (and its relation to other things) and one's sense of the world but they are not exactly or simply parallel to an unconscious/"I-function" distinction either, which is the one I started with. Proprioception, as that term is most generally used, may be either unconscious or conscious, and distinguishes not quite "self " from other but rather one's own body from things outside one's body, which is an interestingly different thing. On the other hand, my sense is that what you are reaching for may actually have less to do with "proprioception", as that term is generally understood (contra "exteroreception"), and may instead be quite parallel to the unconscious/story teller distinction as it has evolved in my own thinking.

For both of us (I think) what we are intrigued by isn't so much proprioception as "body", but rather proprioception as what the etymology of the term makes it seem to be: that which we as individuals uniquely possess, that which is "our own", our "self", and the relation of that to what is outside our self (which can, it turns out include, among other things, the body). The story teller (which I suggest is/creates that) "thinks it has ... a little more information" about one thing than another). Working along the same lines is your interest in phantom limbs, and in the "mild psychological disturbance" that you (I think correctly) see as produced when Burden "supplanted viewers' knowledge-by-sight, awakening psychophysical felt relations to presence in place, space, and time". It is the nature of this "mild psychological disturbance" (which can be common to experiences either of the outside world or of the body) that you suggest is at the core of the Burden performance piece and that, following you, I would tend to argue, is actually at the center of not only much of performance art but of much of contemporary art generally. Let me focus a bit on the phantom limb phenomenon to try and reinforce my sense of the important differences between "self" and "body" (as generally understood in the term "proprioception") and, in so doing, to try and better characterize the "mild psychological disturbance" that is applicable both vis a vis body and vis a vis other things. The first and perhaps most important general difference is that the body can affect the nervous system (via proprioceptors) with or without awareness of it, ie with or without any experience of the body, with or without any change in the "sense of the body". A "sense of the body", on the other hand, is (normally) part of consciousness, ie it is an aspect of the what is created by the "I-function"/story teller" as part of its story. The phantom limb is clear evidence of this. One "experiences" a missing limb not only in the absence of the ability to see it but also in the absence of any proprioceptive sensory input from it (which is destroyed by the same amputation that precludes seeing it). To put it differently, the phantom limb is a creation of the story-teller based on input from the unconscious in the complete absence of any sensory signals at all about or originating in the limb. Without the creation of a story of a self with a limb, there wouldn't BE a "phantom limb". The existence of a phantom limb is inextricably bound up with the creation of a story . Because there is a story, there is a "self" that has a "body" with a "limb". Notice that this is not only a quite different "limb" than would be so identified by an external observer, it is also a quite different "body" AND "self". To an external observer, the terms refer to things they see. Here all three terms refer to story telling elements. From this perspective, what is really interesting to a neurobiologist and, I'm suggesting, in this case, to an art historian as well, is not the narrower question of where a "body" comes from, nor even the broader question of where a "self" comes from, but rather the still broader question of where "story telling elements" of ALL kinds come from, a question that perhaps significantly also recently arose in the mind of a novelist ("How does ... unconscious impulse create ... metaphor?"). I can't fully answer that question, but do think its an important one to be asking in a lot of contexts (including neurobiology) and one on which at this point new progress can be made (cf The Novelist and the Neurobiologist: A Conversation About Story Telling and Making the Unconscious Conscious and Vice Vera: A Bidirectional Bridge Between Neuroscience/Cognitive Science and Psychotherapy?) by thinking more about, among other things, story telling, modern art, and "mild psychological disturbances".

Let's take it as a given that there is a part of the brain (the story teller) whose organization is such that it takes a cacaphony of signals from the unconscious and does the best it can to shape a single coherent story to account for them (a presumption that is consistent with neurobiological observations but the specifics of which require further clarification in terms of neurobiological detail; see The Bipartite Brain). Let's further take it as a given that the cacaphony of signals coming from the unconscious may itself by influenced by things outside the nervous system (both the world and the body) but can also reflect signals originating inside the nervous system itself (that signals can originate within the nervous system is well supported neurobiologically; cf Variability in Nervous System Function and Behavior). Now let's imagine that in the construction of story elements and, ultimately, the story itself (the currently experienced "who I am/what I see/feel/think/am doing"), the story teller looks repeatedly compares candidate stories with the unconscious inputs, looking for consensus support for particular elements of the story. Those elements with lots of consensus support are solid/firm/"real" and those with less support are less so and, in turn, make less stable the overall story of which they are a part. Bingo, a "mild psychological disturbance", ie some instability in the overall story, when some unconscious signals support "Burden is on the platform" and others ("seeing") don't. "Mild psychological disturbances" of exactly this kind are associated with both motion sickness and jet lag, other cases in which it is difficult for the story teller to achieve easy consensus across signals coming from the unconscious. In those cases, of course, there tends to be less "artistic" benefit. But one might well imagine that contemporary artists are discovering that the fact that "mild psychological disturbances" of related kinds can in fact create somewhat unstable stories that have more appeal, that viewers are attracted to for a variety of reasons, including, perhaps, their function, a stimulus for new kinds of thoughts/explorations that in turn lead on to an improved story telling capability overall. Much of surrealism makes sense, it seems to me, in these terms. As does a significant amount of both performance and installation art? I was at MOMA last weekend, and there is a piece there in the contemporary galleries (I didn't get its name or that of the artist) that involved entering a dark space within which there was a blue .... something. Much of the power of the piece (for me at least) related to the fact that one was unable to determine with any certainty exactly what its shape was or where it was located with respect to one, and so the "story" of it was highly (and intriguingly) unstable. This "story" of mine built on yours is, of course, itself of uncertain stability but, in going back to the fragment of the essay you sent, I'm struck by "Burden's own title obliquely referred to the physical and visual effects of heroin, including sensory deprivation ...". Clearly the degree of stability of "story" and the destabilizing effects on story of reduction of sensory input (this is in fact one of the strongest lines of evidence for signals being generated inside the nervous system: reduction of signals coming from the outside enhances rather than diminishes story production) was a major consideration on Burden's mind. So, perhaps another bit of support enhancing the stability of this particular jointly constructed story?

|

KS to PG, 22 October 2005

On the contrary, you have not given me too much. Your response is terrific and just what I needed. Far too few scholars share their time, work, or thought processes as generously as you have and I am very grateful.

| while I understand why you shifted to the term story teller, I think it is too soft ... and pushes the concept of the "I-function" toward myth, folklore, and territories of experience that must by definition remain vague, open, and fluid |

More to the point, there is an intriguing overlap between the brain-damaged, "blindsighted" person you describe and Burden's sight-deprived viewers in terms of the operations of consciousness and unconscious (even bearing in mind the baggage to which you refer, as well as your point that, "All incoming sensory information goes first to the 'unconscious' part of the nervous system and only subsequently and after processing there does it reach the 'I-function'"). But as Alain Berthoz writes in The Brain's Sense of Movement (Harvard, 2000), "[K]inesthesia's [namely aspects of proprioception] characteristic feature is that it makes use of many receptors, but remarkably it has been forgotten in the count of the senses." One "plausible explanation," for this, he adds, "is that it is not identified by consciousness, and its receptors are concealed (25)." Thus, clearly Berthoz and you (as well as I in the context of art) are attempting to discuss a phenomenon that is itself invisible and its markers - unlike the other senses - are also invisible. On this point you write, " we (our I-functions) have no direct information about what is 'out there'." So what I am suggesting is that what may be happening in the body of viewers, in Burden's body, in the blindsighted people, in proprioceptive aspects of kinesthesia, is unknown but related, which is very different from suggesting that it is unconscious.

In addition, I'm not sure that what one reports about experience should be called only "interpretation" (even if it literally is) since it would be the same for anything one would say about the body's sensations, perceptions, and senses. As we do not speak in terms of brain functions, synapses, or the operations of the nervous system when we report on experience, it seems dismissive to call what we are able to say "interpretation," thereby diminishing the authority one has over describing one's experiences. Therefore, I don't think it's useful to talk about the "I-function" as "interpretation." OK. I know this is odd - to have someone (especially in the humanities) arguing with you about your own concept, but here we are.

Let me tell you then why I like your term "I-function." It directly indexes the source of proprioceptive experience as it belongs properly to the body/person, or we could also say "a person's body." As far as proprioception (or the I-function) being "creative, arbitrary, discretionary," non-verbal but language-dependent, my thought would be "of course." But whereas for me as an art historian/theorist that does not pose a problem, for you as a scientist/theorist it poses the usual problem of the worn out scientific method, which cannot answer anomalies or the unexplained. You seem to be approaching those territories when you want to extend proprioception to whole "communities or other less individualized, egocentric actors." While I believe that such communal senses can and do occur, at least for the purpose of locating a place for discussing the conditions of proprioception in the brain, I'd rather stay in a more confined (controlled?) frame of reference. Lest I appear to be throwing Polyani back at you by pointing out that science itself is not value free, etc, let me just say that I'm trying only to stay closer to the topic of the I-function, which seems to me to wander too much when it becomes "story-teller." And of course what one reports is infused with all kinds of extraneous - or not - experiences and perceptions. Still, we have to say something in order to communicate.

What I was trying to get at is that "something" took place between Burden's absent body and the bodies of his blindsighted viewers, and that it had something to do with proprioception. Moreover, what I am most interested in is that proprioception has something to do with survival. On that point Berthoz made a very provocative, but truncated observation: "A muscle actually contracts very slowly. It attains its maximum force about 80 milliseconds after a neural command. Eighty milliseconds is a very long time ifc you are trying to get away from a predator (28)." Berthoz did not emphasis the sentence about predators, I did. The problem of proprioception, as I see it, is its relationship to survival - or as you put it (not intending the question of survival): "There is lots of information about the body that is being used by the unconscious to control behavior without it being transmitted to the I-function/story teller in any form that makes it apparent in the story as a distinct kind of information. Without our being 'conscious' of it [even as to say that we are unconscious is equally wrong]." I understand this tension. But the point for me is not "story telling," again it is survival; and how the body is calibrated to do just that, how we have lost connection to that calibration - I ride horses and see their proprioception/survival efforts vividly all the time. (By the way, I do understand that proprioception refers to the "very large group of sensory neurons that...report to the nervous system information about the state of muscles, joints... etc)," as you write; indeed, my first brush with proprioception was in the dentist office when my bite needed to be recalibrated.)

| the point for me is not "story telling"... it is survival ... "I-function resonates just on that point, primitive/survival ... and relates directly to Burden's work ... |

As an historian of contemporary art, I would have to argue that only some kinds of art - in particular body art, action art (I actually hate the term "performance" for its connection to theater, which the best of body art decidedly is not) - access this primitive survival function. Your term "I-function" resonates just on that point - primitive/survival - so broadly for me and relates directly to Burden's work. Furthermore, the "psychological disturbances" to which I have referred are also related to survival mechanisms, which I do not recognize as related to what you describe as "the instability in the overall story." On the contrary, they ARE the story and it is not unstable at all, but rather demanding, threatening, and necessary. (Tangentally, Surrealism has some areas of cross-over in so far as there would be no body/action art without its effort to get into the unconscious, without Abstract Expressionism further interpretation of autonomatism, without Happening artists further reinterpretation of Pollock's automatic painting as body-centered and therefore an action that rendered painting unnecessary altogether.)

So I come to the end of my response. Are we in this long exchange at an impasse? I've arrived at survival and you are telling stories about the stories we tell ourselves neurobiologically/socially. Perhaps we can agree that this is the broader territory of proprioception?

|

PG to KS, 30 October 2005

What might under some circumstances be "impasse" is, in this case, as intriguing and promising a challenge as I could ask for. From this end too, "your response is terrific and just what I needed ... Far too few scholars share ... as generously as you have and I am very grateful." Too. And so I too "keenly look forward to continuing this dialogue" and to the various things we might make of it. Hence, without further ado .... I really was/am/continue to be very gratified that the "I-function" concept resonates with/seems useful to you. And I think I now have a still better understanding of why. Moreover, you have taught me something useful about my own neologism. I won't give up what is, for my purposes, a needed adjustment/extension of the original idea signalled by my tendency to shift to "story teller", but have already found myself sensitized to the point where I think twice before using "story teller" (and often end up, not particularly elegantly, using "I-function"/"story teller". Let me try and walk through why this is so, certainly for my benefit and perhaps (hopefully) for yours as well. If I'm reading your latest correctly, there are three features of proprioception and the "I-function" that are very compelling to you and that link them importantly. One is that "it belongs properly to the body/person", a second is that it "has something to do with survival", and the third is that it is "primitive". The upshot, if I'm understanding, is an argument that Burden's performance and the audience reactions to it constitute a form of art in which the exchange between artist and audience is at least quantitatively and perhaps qualitatively different from the much more mediated/interpretation-dependent exchange characteristic of many other forms of more "traditional" art. Assuming I've got this right, I agree with your conclusion, and am quite happy to have my neologism contribute to your argument.

More than that, I am pleased and grateful to have you point out aspects of the neologism that were implicit in it but are very much worth making more explicit. That the "I-function" has "something to do with survival" is a characteristic that is so assumed by me as a biologist that it would never have occurred to me to flag it as distinctive, but I now recognize the desirability of doing so in contexts where one is talking about things for which that presumption may not be automatic. In such contexts, I can readily see a usefulness in drawing attention to a distinction between things that may have more "to do with survival" and things that have more to do with .... something else (cultural norms? personal display? "aesthetics"? commercial return?). "belongs properly to the body/person" is even more certainly an intended feature of the "I-function" neologism. In this case, though, I suspect my failure to adequately emphasize this particular feature has the opposite relation to context. Until quite recently, the notion of a meaningful "self" (something to which one might reasonably and productively attribute ownership) was not something within the professional vocabulary of very many neurobiologists/biologists/scientists (and its still probably not for very many). So I was looking for a term that finessed this particular issue. As it happens, one of the things that I have found most useful about the term is that it has given me a new (for me at least) way to think about the meaning of "self" (and ownership). For this reason, I am more than content at this point to have it made clearer that the neologism helps to make distinctions between things that more have the characteristic "belongs properly to the body/person" and things that less have that characteristic. You may have detected a certain carefulness in the wording of that last sentence. Yes, I'm being deliberate/cautious here, for reasons I'll discuss more fully below. And I want to be even more so with regard to "primitive". The issue is not the question of possible value judgements associated with that word. I assume that you, like I, use "primitive" not as a pejorative term but rather as a neutral (or perhaps even positive) one (cf "'Primitivism' in 20th Century Art") to distinguish things that are in some sense more "basic" or "fundamental" from things that are less so.

In short, there is a matter of reference perspective here, what is more "primitive" from one location is less so from another. And part of the reason for creating the "I-function" neologism was to assert for people more familiar with more "primitive" things, the existence/significance of a less "primitive" one. That having been said, it has been, and will continue to be useful, even in my context, to emphasize more than I did originally, the "primitiveness" of the "I-function" relative to some other things. Among these, as I'll come to below, is "self". The upshot, at this point, is that I accept and acknowledge with appreciation your highlighting three features of the "I-function" that I placed less stress on than I perhaps should have: it is more "primitive" than some other things, has more to do "with survival" than some other things, and is more something that "belongs properly to the body/person" than some other things. And I share your sense that we are both "seeking to describe aspects of behavior and cognition that have been far too long unexplained, or left at the edge of explanation". And I like a lot your notion that "what may be happening in the body of viewers, in Burden's body, in the blindsighted people, in proprioceptive aspects of kinesthesia is unknown but related". So where do we see things differently? There is clearly a difference of audience and reference perspective but is there something more? Anything else that we (and our respective audiences) might both learn from? Anything that might account for my inclination to continue transforming "I-function" into "story teller" despite all of the above?

Yes, it is indeed odd (and another part of our inverted postures) to have you (as a humanist) be resistant to talking about what the "I-function" does as "interpretation". I do though very clearly understand your concern that in doing so, one risks being heard as "dismissive" of the thing being talked about, as in "oh, that's only an interpretation; so I can ignore it in favor of something else". I assure you I don't at all intend to convey with "story teller" a justification for being dismissive in this way (or any other). The point here is not only that what the "I-function" does in this case is "literally" interpretation but, more generally, that EVERYTHING the "I-function" does is interpretation, so saying that a particular thing is interpretation CANNOT be dismissive. There simply isn't anything else to ignore it in favor of. All "experience", things in awareness/consciousness, are indeed "interpretations" in a very important sense: they reflect interactions of neurons/synapses/etc occurring in a way that is "itself invisible" and that could occur in other ways that would yield alternate interpretations/experiences. I share your notion that it is important to avoid "diminishing the authority one has over describing one's experiences" but think one gets into several kinds of avoidable troubles if one tries to do it by denying that the thing one is interested in shares with other things an important common property of resulting from interpretation. And yes, one would like to avoid the mishmash of "infused with all kinds of extraneous" things but here too I think there are better ways. What one wants, from my perspective (and perhaps yours as well) is not to make a distinction between not interpreted and interpreted but rather to recognize a distinction between self and other that acknowledges some degree of interpretation as an element of both but yields more "authoritativeness" in the case of self .... without getting into a mishmash. On the route to that (perhaps), let me raise an issue about "what may be happening in the body of viewers, in Burden's body, in the blindsighted people, in proprioceptive aspects of kinesthesia, is unknown but related, which is very different from suggesting that it is unconscious". If you heard/read me as suggesting that the similarity among these things was that they are all unconscious, then, given how well you've made sense of other things, I was not communicating well on that particular point. In fact, the similarity that I was trying to draw attention to (and that I think is quite close to what you are interested in) to is a similarity in consciousness, in experience. What is common in all these cases is not at all that they are all unconscious. If fact, they all must have aspects of consciousness.. If they didn't, they wouldn't be reportable as experiences and we wouldn't be talking about them, much less intrigued by possible similarities among them. Nor is there any reason to think the similarities relate primarily to what is going on in the unconscious (the neurobiology implies they involve quite different neuronal systems doing quite different things). Hence the similarities among these things must have to do with similarities in the conscious realm. The similarities are not actually similarities "in the body of viewers" and in "Burden's body" nor in the unconscious of viewers and in Burdens' unconscious but rather in the experiences viewers have of (perhaps) their bodies, in the experiences Burden has of his body, the experiences those with phantom limbs have of their bodies, the experiences you have of your body when riding a horse (or having your jaw reset), and the experiences blindsighted people have of the world. To put it differently, the similarities are similarities at the level of the more interpreted thing (conscious experience) that are not present at the less interpreted one (things happening in the unconscious; this is one reason I want to emphasize the interpreted character of the I-function). They are similarities in the "story telling" elements rather than in the materials from which the stories are constructed.

The issue here is not solely technical or "semantic". What I'd like to persuade you of (or have you dissuade me of) is not only that one can accept this particular interpretive step without cost (either to a sense of "authority" or by getting lost in the "mishmash") but that it opens things up a bit in some positive ways. One is NECESSARILY the "authority" with regard to one's sense of one's body or one's sense of one's self precisely BECAUSE it is an interpretation. It derives from things no one else can see and from an act of interpretation that no one else can duplicate. Hence one is the only authentic reporter of what one experiences with regard to body/self. One is, of course, the only "authentic" reporter of what one experiences oneself with regard to "other", the large additional class of story telling elements that includes things like chairs, tables, paintings, body art, Chris Burden, art historian, neurobiologist, and so forth). These though are consensual story telling elements, aspects of the interpretive activity in going form the unconscious to consciousness that we (most of us, to varying degrees) have collectively agreed relate not to "us" but to commonly observable "others" and so are subject to continual negotiation and renegotiation by interpersonal story comparison. Hence the "mishmash", which actually results not from the interpretive character of story telling elements in general but rather from an additional ingredient of some of them: the potential usefulness of trying to achieve consensus among a group of story tellers. In talking about one's own body/self, the mishmash is (doctors and parents notwithstanding) irrelevant; one is, for these particular story telling elements, the authority. They may also be more primitive or foundational in an additional sense. Antonio Damasio (a neurobiologist who you might be interested in reading if you haven't) has written extensively about the origins of a sense of body/self and makes a strong case that these story telling elements reflect a distinction between a "proto-self" and other that originates in the unconscious. At the same time, since body/self ARE story telling elements and hence interpretations, they are not fixed and unchallengeable. One's sense of body/self can and does change (with input from other people not being completely irrelevant), and one can conceive of bodies/selves other than the one one has and use one's alternate conceptions to change one's own sense of one's body/self (trans-sexuality is a particularly dramatic case in point). This might seem to undercut the argument made above for the absence of mishmash and resulting "authority" in the case of body/self as story telling elements. In fact, I don't think it does. These elements are MORE "foundational" and "primitive" than others but not entirely fixed, and it is because of their lability that we have some control over ourselves (which I take as, at least potentially, a good thing). One can have MORE primitive, MORE "belongs properly", MORE "has to do with survival" without having to give up the potential for self-directed change that comes from being an interpretive outcome, a story telling element.

Whether it works for you is of course your story rather than mine (and I'm very much looking forward to finding out). Let me though return briefly to Burden and "mild psychological disturbances", and my own understanding of them (informed by your article). I fully agree with you that the responses to Burden's work are MORE "related to survival mechanisms" than are many of the more traditional responses to many more traditional kinds of art. And that they "ARE the story .... rather demanding, threatening, and necessary". My point is not only that they are indeed "story" (ie experiences of which viewers are aware, and hence interpreted) but that they are fundamentally dependent on story in an interesting way. Viewers would not, I'm suggesting, have had "mild psychological disturbances" UNLESS there was a story that could not be quite squared with the signals coming from the unconscious ("He IS there, but ... Isn't he?). That's what I meant by "an instability in the overall story". Not that the story wasn't "demanding/threatening/necessary" but rather that that those characteristics of the experience derived from a difficulty in the viewer's ability to settle on a single coherent story about the situation. That, in turn, is VERY "demanding, threatening", in much the same way that motion sickness is. Indeed, for humans an inability to be certain of a story may be the most threatening thing there is (even if it isn't actually a threat to "survival" in many cases). And can/does itself trigger new signals from the unconscious that may get added to the story as signals referred to the body (nausea in the case of motion sickness, "tension" and "edginess" in other cases). Did something "take place between Burden's body and the bodies of his blindsighted viewers"? Not directly, so far as I know (as a neurobiologist), but it certainly did via the mediating influence of at least one set of story tellers (those of engaged audience participants) and probably two (Burden himself). Enough for now? Almost certainly more than. But I can't resist looping self-reflectively back to our differing contexts, to our oddly inverted postures, to "too soft to support ... vulnerable to colonization", and to "rather stay in a more confined (controlled) frame of reference". With perhaps a dose of Pollock as well ... I'm intrigued by your "reinterpretation of Pollock's painting as body-centered and therefore an action that rendered painting unnecessary altogether". Pollock (and the surrealists before him) were indeed interested in what could be produced by action alone as opposed to deliberation/thought directed action. And I can understand that as "body-centered" though I'd be inclined to emphasize in this case not so much the body as the unconscious. All action is necessarily through the body and both from and via the unconscious; the issue is the extent to which it is or isn't informed as well by passage through the story teller on the way to outward expression. Western culture, and academic culture in particular, tends to put great pressure on people to constrain outward expression to that which has been passed through and edited by the story teller and often through multiple story tellers (reviewers, editors, and the like).

On the other hand, there are also downsides to thought/reflection/story telling/craft skill. As Pollock and the surrealists (among others) realized, there is lots of interesting and potentially productive stuff that might not make the various cuts represented by various testing and validating mechanisms and so would never see the light of day. One's own story teller makes some of these cuts; the academic world encourages that kind of cutting and of course does more of it itself. In addition, the academic world tends to restrict the flow of stories, largely channeling them within particular disciplinary communities. Maybe, as per our own exchange, there is something to be said for reducing the domination of the story telling process? Or at least creating avenues for less mediated/interpreted exchange? Yes, it puts one at risk of having to wade through more stuff, discriminating among things oneself rather than having it down for one. And yes, the lessened rigor might make one more challengeable, and perhaps even open the conversation to .... kooks. On the other hand, maybe even kooks have useful stories and perhaps the price overall isn't too high given the potential benefits? We don't seem to me to be doing too badly. |

KS to PG, 30 October 2005

I have dashed through your amazing letter and cannot give it my serious attention just now because I am leaving the country Wednesday ... I promise to get back to our challenging and engaging discussion when I return.

But I couldn't miss the chance to say that, of course, I agree with you about the word "primitive" and most heartily enjoyed the debate over MOMA's inappropriate use of the term ... Back to the word primitive, which I'd like to replace for our conversation with the word "animal." Is it possible that proprioception is a sense like the appendix is an organ that has mostly outworn its purpose for survival? Could we say this about so-called "psychic" phenomena and its relation to human animality and our survival?

You are right to say that we have both adopted the stereotypical mode of each other's disciplines in our "oddly inverted postures." I read your reason for doing so as exactly the same as mine, but opposite. I do so (probably defensively) because the material I work on is so fraught (for most people), especially scientists. After all, I work on the "craziest" of artists (Performance and Conceptual Art); on animal studies (especially horses); and, I'm not afraid to tell you that I also research such anomalies as psychic ability, about which I have written, lectured, and argued that it has something to do with survival/trauma/our "left-over" animality, to say nothing of the weird areas of quantum physics where electrons in super position act just the same way that the local psychic operates. OK - that's out of the closet. Now you may better understand the interest/overlap in my thinking about the cluster that includes body art/survival/animality (our "primitive" being)/anomalies of behavior and modes of knowing.

Can't close without also fessing up that you have unearthed something in my unconscious that I wasn't quite aware of until I met up with the phrase "story telling." Maybe I called it "soft" because I have an irrationally negative response to the notion of "story telling." ... So I want to ... think about about your letter carefully so that I may respond from the conscious self.

Can't close without also fessing up that you have unearthed something in my unconscious that I wasn't quite aware of until I met up with the phrase "story telling." Maybe I called it "soft" because I have an irrationally negative response to the notion of "story telling." ... So I want to ... think about about your letter carefully so that I may respond from the conscious self.

As for Pollock becoming boring: Check out "Portrait and a Dream," done just three years before he died. You won't be bored by it.

KS to PG, 13 November 2005

Clearly, we have not come to an impass but I do remain unconvinced by the term "story teller," and have had an opportunity to think more about it in the intervening two weeks whilst in England. Let's be clear that the following objections are deeply related to the interface I have found between "body art" and your concept of "I-function," so that what I have to say pertains directly to art. But it may be relevant for your future development of the concept.

| I want to propose that "story teller" remains confined to the realm of metaphor (and, thus, epistemology), from which I took partial flight in moving from traditional painting and sculpture into body art where metaphor is, certainly, in operation but which appends the conventional metaphorical aspects of art with metonymy. Your term "I-function," in my view, is metonymical, namely more directly connected to ontology. |

I played around with terms like "reporter" but could come to nothing satisfactory to replace "I-function" for its description of the body (however invisible and conscious or unconscious of what it describes may be/is). If I put it another way, I could say that "I-function" is more "undressed" than "story teller," but this is also a metaphor. The "story teller" may don any clothing s/he wishes for the tale. What attracted me to "I-function" is its proximity to naked truth, which is not to say that when one says "I" s/he is speaking the truth. Hardly. What I said is that one is "closer" to the truth. Of course the "I" can story tell, probably does most of the time, especially when it comes to proprioception (as you point out), which it cannot "know" but about which it can only "tell." Nevertheless, I submit that at least with the term "I" one approaches conditions of being more readily and immediately than with the term "story." Moreover, as we both recognize both are "tellers," the "I" as much as the "story."

| Pollock, as another example, was not telling a "story" with his drips and pours; I would maintain that he was visualizing the function of his "I," his "I-function." His paintings were to him what the crown is to the king/queen, what the red beard is to the man - a contingent extension of the function of his "I," which has nothing to do (necessarily) with a "meaningful self" but with a functioning unique being. |

Which brings me to my request to replace the term "primitive" with "animal." I used the word "primitive" to refer to the animality of being that connects the human animal to a former state of being and its proprioceptive needs and conditions. In that prior state, they were more immediately related to daily survival whether in terms of food or reproduction. As I noted in my last communication, I am quite convinced that this animality is operative in the human animal, and is one of the ways in which it betrays our human connection to our animality. Because I work on trauma and its representations in art, literature, and film, I am acutely aware of the immediacy with which the human animal still relies on its more primitive states to survive. (Here I use the term primitive in the sense that I meant it from the beginning.) In my view, all of this comes into play in body art where even if the narrative content of the action is not about survival per se, the body is always already in that mode of survival.

So let us return to Burden's "White Light White Heat," during which his "I-function" was operative as a survival function over 22 days of fasting and remaining unseen on the platform above the sight lines of the viewers. And, by the way, who knows if pheromones were operative in communicating proprioceptively from Burden to his sightless viewers? We know, of course, that pheromones are chemicals emitted by living organisms to send messages to individuals of the same species. So is it not possible that in addition to perceiving the survival conditions of his situation intellectually, the audience for his invisible action may have also felt them, proprioceptively? This brings me back again to the question of a "meaningful self," which has nothing to do (or at least little to do) with pure survival transmitted on "the level of brain regions, circuits of neurons, neurons themselves," etc.

Another problem with the term "story telling" (or the word you often substitute for it - "interpretation") is the way in which it raises all kinds of moral questions about use. How one uses story telling is quite different from referring to the "I-function" of one's proprioception. Furthermore, I don't really see why the term "story telling" is any more unfixed than "I-function." One is more immediate, closer to the subject, than the other - that's all. So, no, while I appreciate the effort towards a "more nuanced" description of "story telling," and while I agree with everything you say about story telling, interpretation, consciousness and unconscious, the problems of a "meaningful self" and so on, these efforts to substitute that neologism for "I-function" are unconvincing.

| "Whether it works for you is of course your story rather than mine" is a comment that represents everything I mistrust about radical relativity even as I recognize that this sentence is true. Fluidity is desirable but not if it means there are no boundaries, which everyone, everything, needs for stability. |

As for your daughter being a painter and my comment that "action rendered painting unnecessary altogether," it was not an a priori universal statement about the continuity and significance of painting, but a comment about the context of the evolution from Pollock's paintings to happenings, body art, and performance. As a painter myself, I would hardly say that painting has no place in the present: it does and I wish your daughter the best in that endeavor.

I am going to close now, not because I don't have much more to say. But what I have to add really takes this conversation in the direction of survival and the animal/being, which I have learned is far beyond the realm of what you meant by "I-function."

Wow. Resonances on multiple levels and in multiple ways. Happy to follow you in the direction of "survival and the animal/being", but let me put a few more things on this table first, and perhaps try to tidy up a bit here before we head out?

So, I ask myself, why didn't I point to a metaphoric/metonymic distinction in our conversations to date? And why have I (I now notice) not used that distinction in some of the more formal writing I've been doing recently on these issues, nor in much of my teaching (though see musings)? The answer is, I think, very relevant to what we're trying to sort through. To use the metaphoric/metonymic distinction with most people one first has to teach it to them, and in trying to do that my experience has been that one runs into all sorts of complexities. Yes, indeed referring to a man as a "red beard" almost certainly reflects in its origin a substitution of one thing for another based on more directly perceived spatio-temporal relationships. But it has become by usage also "metaphorical", ie a substitution based not on the more direct experience of an individual but rather on having seen/heard that substitution being made by others. Conversely, some substitutions that clearly have their origins in metaphorical processing ("country" and "flag") may take on, for individuals, the "feel" of being related metonymically, ie without abstraction or thought (whether they ARE in fact represented metonymically is a very interesting neurobiological question).

It is not just that a distinction that seems so obvious and useful to some people (me and you among them) is less obvious to others but that it is less obvious for a particular reason: it is hard in general for people to get a handle on why they make particular associations between things. Moreover, the reasons may be different for different people, and may be different at different times for the same person. To put it differently, there is "story", ie what we consciously experience/think, and then there is .... what despite all our efforts we are less clear about, less able to be sure of (the unconscious, or "tacit"). And things can move, in both directions, between them.

My point in all this is not at all to quarrel with your suggestion that "story teller" is "metaphoric". Indeed it is, not only in the obvious sense that it is a language term (though I will argue below that language is not in fact necessary for metaphoric processing) but also in the deeper sense that it is a term more removed than other terms from what I (or others) more directly experience. It is a higher order abstraction, itself the result of a long period of negotiation between .... my unconscious and my story teller. And, as such, it reflects organizational features of both, most notably (because of the story teller) an inclination to try and find similar patterns in an array of different more direct experiences (this is "like" that, very much amplified and extended). From the latter, it is appropriately concluded, at the deepest level, that indeed the "story teller" feature of the brain encompasses metaphorical processing.

I do, though want/need to contest your conclusion that the "I-function" does not. That which is "more directly" experienced is ... experienced, and hence must, in my terms, involve the story teller. It must, at least to some degree, therefore be affected by the metaphorical character of the story teller, the effort to try and find common patterns across a wide array of different things coming from the unconscious. George Lakoff, in Metaphors We Live By and Philosophy in the Flesh provides a number of good examples of hidden "metaphors" in a variety of aspects of things we tend to think of as our most "direct" experiences. In his enthusiasm, I think Lakoff goes to far with his argument, implying that there is actually nothing BUT metaphor (which he confuses with categorization or abstraction, a more general process; one of the virtues of the story teller idea for me is that it helps to provide a needed distinction between abstraction and metaphor; more on this below). Nonetheless, Lakoff's examples provide strong evidence that there is some involvement of metaphor in everything we experience, no matter how "primitive" (or "animal") . The "I-function" is MORE primitive/animal than some other story features but insofar as it is experienced it is part of story and so less primitive/animal than others (cf "treeness").

In short, I appreciate very much your bringing the metonymic/metaphoric distinction to the table, and would like to keep it here, with the hypothesis (at least) that the unconscious operates metonymically and consciousness (the "story teller") uses metaphor as a way of making sense of what it gets from the unconscious. I can't agree that the "I-function" is not metaphoric, but am willing to agree that the "I-function" is MORE "contingent to the being for whom the experience is being narrated as I", ie that it is CLOSER to .... what comes from the unconscious than some other things the story teller does. And in this sense more "naked"

You'll notice that I'm avoiding saying, closer to "truth", replacing it with "what comes from the unconscious". As you say, there is no assurance that "when one says "I" s/he is speaking the truth". This is one of a number of reasons to try and avoid that word wherever possible. Because of similar arguments, I'm declining to make an epistemology/ontology distinction. In my terms, there is ONLY the things coming from the unconscious, and the sense made of them by the story teller. The problem of the meaning of things is inextricably entangled with the problem of what is, so there is for me no clear distinction between the two, no way to evaluate truth, and .... nothing but the unconscious, the story teller, and negotiations between the two.

There IS though, for both aspects of story (experience) itself, and for different story telling styles ("primitive", sophisticated), a legitimate and appropriately noticed difference in degree of "nakedness" in exactly the terms you define it: Burden and Pollock were trying to make evident themselves, their "I"s, rather than their more abstracted understandings of other people or the nature of art or .... any of the other things more distant from the unconscious that artists (and others) sometimes try to make evident. Your use of the "I-function" to signal this is entirely appropriate. And my insistence that the I-function is a subset of the story teller shouldn't in any way detract from that. Burden and Pollock were/are doing in art what Beckett and Virginia Woolf (sometimes) were doing in literature: exploring how to tell stories that stay close to the unconscious.

The bottom line is I'm not any longer trying to to "substitute" "story teller" for "I-function". I'm not actually sure I was originally, but agree it sounded enough that way to justify your concerns. In any case, you've more than persuaded me that "I-function" and "story teller" should not be regarded as alternate terms for the same thing. Game, set, and match to you on this issue. I will keep "I-function", and use it happily in the extended senses we've discussed. I do, however, still feel a need myself to move beyond "I-function" to the more encompassing term "story teller", and perhaps to persuade you that the more encompassing term is at least as interesting as the term it contains. Let me try and say why.

What seems to me appealing/useful about the primary subdivision between unconscious/tacit/metonymic and conscious/story teller/metaphoric is not only that it is at least reasonably well-defined operationally (and at least partially so neurobiologically) but that it provides a framework for making some other distinctions that it seems useful to be able to make (its a "good" metaphor in that it makes sense of a disparate array of things?). The distinction between abstraction and metaphor, mentioned above, can, for example, be made in terms of the absence or presence of evidence of "an inclination to try and find similar patterns in a wide array of different more direct experiences". Perhaps more immediately germane to our conversation is that the primary subdivision provides the basis for substituting for the more awkward concept "truth" the somewhat better defined "comes from the unconscious". The "I-function" is not in any sense closer to "truth" than some of the other things your colleagues in art history work with (more on this below), but it IS closer to the unconscious.

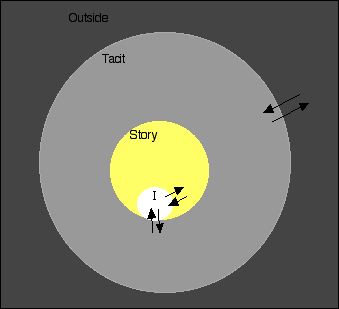

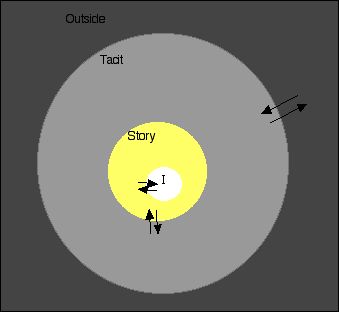

In the diagram to the right, the "I-function" is clearly "closer to the unconscious" in the sense that tacit knowledge is shown as going first to the "I-function" and only subsequently being distributed to the rest of the story teller. This would be a particularly simple way to account for the "I" as more immediate, more direct than other story telling features (those being fundamentally derivitive of the I-function). But its not the only way, and my intuitions say it is not the most likely one. So, a more general purpose version of the diagram below.

I won't try to adjudicate among these possibilities at the moment. For the present, my point is simply that neither the I-function nor the questions you're interested in disappear if one uses a basic tacit/story teller framework and, moreoever, that that framework provides a way to develop further lines of exploration that may help to shed additional light on questions that we're both interested in. How about that as a little tidying up? We keep the "I-function", situate it somewhere within the story teller, and go from there? I can already imagine some additional visual images in which we play with separate and intersecting signal paths related to the body, proprioception, and other things.

"Naked," "primitive," and "animal" all make sense in this framework as well, as long as one treats these as RELATIVE rather than absolute: the I-function and its expressions are MORE naked, MORE primitive, MORE animal than some other aspects of story telling because they are closer to the unconscious. Though this doesn't grant them either absolute or uninterpreted status, it does allow one to distinguish, as you want to do, between a kind of art closer to the undressed body/self and art of more rarified/culturally sophisticated kinds. And to do so in a way that inverts more traditional judgements by making the primitive/animal foundational to the other kinds.

All of this bears as well on the matter of "survival". Yes, indeed, the "human animal still relies on its more primitive states to survive", precisely because the I-function, and the broader story teller of which it is a part depend on the unconscious as their primary reporter and analyzer of what is going on and as the substrate through which they have to work to do anything about it. The I-function may convince itself at times that survival depends on a favorable review of a museum show, a successful tenure decision, or the outcome of an arcane academic debate, but it is in fact sitting on the back of an unconscious that in general has much greater skill at and influence on survival.

Here too, though, one doesn't need or want to overstate the case. No, I don't think that "proprioception ... has mostly outworn its purpose for survival". It, and the unconscious, are a major part of whatever successes humans have as biological entities. On the flip side, though, being relatively more foundational doesn't mean that they are necessarily "wiser" in any given situation. Sometimes the less foundational acts of "thinking" are useful too. And part of what makes them useful is that they can in fact produce changes in what is more foundational ("I am, and I can think, therefore I can change who I am"). This is not actually a contradiction in terms. In biological systems, one frequently sees both "bottom up" and "top down" influences, so that things out of which other things are constructed are not fixed and invariant but rather themselves influenced by the constructions of which they are a part (cf From the Head to the Heart).

Its a short - and welcome -step from that to "moral questions" and "everything I mistrust about radical relativity even as I recognize that this sentence is true". And perhaps to ... "trauma"? I readily admit that I .... am less sympathetic to/moved by "trauma" than many people are, and not infrequently get into trouble on this score. I may here with you as well but ... we've built a bit of a platform (a revisable foundation?) so far by trusting each other and the only point is seeing what more we can do with it so ...

An easy (I hope) step first. I am indeed what I think you intend by the term "radical relativist." My path to that position, however, has been not the postmodernist/humanities route but rather one through science, biology, and neurobiology (mixed with a little existential philosophy and seasoned by growing up in the sixties). Perhaps for this reason, the notion that everything is a story is for me not a final position but a take off point for further inquiry. "IF one begins to have the feeling that there really ISN'T any such thing as "Truth" or "Reality" outside oneself, at least not a useful one that one can rely on as a fixed and stable motivator of and guide to one's own behavior, AND one has the feeling that PC/postmodernist solipsism (all stories are equally good) is not an adequate response to this feeling, THEN ...." (On Beyond Post-Modernism: Discriminating Stories) one needs to come up with a new and improved understanding of how to proceed.

I think that the tacit/story teller framework (with the I-function in it), combined with a sophisticated appreciation of evolution, gives us a promising opening for that improved understanding. Yes, a certain amount of stability is desirable at any given time. One needs a platform to take off from. On the flip side, "fluidity", I would argue is not only equally desirable to one degree or another but also ... inevitable. Humans may desire stability but they are, as biological entities, both products of and contributors to fluidity. Inevitably and unavoidably so.

All that you Change

...... Octavia Butler, Parable of the Sower

One can, as a story teller, either fight that or embrace it. To embrace it is not to become passive but rather to acknowledge/respect/even celebrate one's existence as a meaningful change agent. And to acknowledge/respect/encourage the same in others

It is precisely BECAUSE of the story telling feature ("nothing is definite"), and the existence on an "I-function" as a component of that (a story about onself and about one's relation to the world that is itself not definite) that we have the ability to conceive things (ourselves included) as other than we are at any given time. To conceive, and attempt to bring into existence, alternatives. To make art, science, and ... revolution. Some stories prove better than others at achieving this potential, and so not all stories are equal; there is a way to discriminate among them. Hence one need not fear story telling as either solipsistic or amoral. It is instead not only an inevitable feature of the human condition but one that gives us the wherewithal to conceive/critique/reconceive our selves, our cultures, and morality itself.

What about "radical relativity" and story telling for "someone who has had their world unseated, whose boundaries have been transgressed, whose sense of trust is gone, whose fear of the elements (tsunamies and hurricanes) is profound such that they cannot function ... [who] must have a story that s/he can share with others and believe?" There could indeed be a "problem of use" issue here, of "meaning derived in use", ie of context dependence. Perhaps "traumatic experience" makes someone sufficiently different from other humans so that story telling as radical relativity is at best irrelevant and at worst unsympathetic, even abusive?

"Trauma" is your area of expertise, not mine, but let's see if I can perhaps contribute to your thinking about it (as you've contributed to mine about the brain). My uninformed feeling is that traumatic experiences do not in fact put those having them into a separate category from other humans, that instead the experiences cause such people to be more aware than most of us are (or choose to be) of the deep nature of the human condition, one common to all of us. Many of us act much of the time as if there are reliable fixed points to our lives that we can rely on unquestioningly to give "meaning" to what we do. Could it be that it is the destruction of one or more of those fixed points that makes experiences "traumatic"? That people having such experiences are thereby forced to confront the human condition that there are in fact no fixed points that can be unquestioningly relied on, and that "meaning" is always story created for oneself out of whatever materials one has at hand?

If so, an understanding of "radical relativity" and story telling might actually be therapeutic in dealing with trauma, a way to help people see themselves as creative agents rather than as irreparably damaged, and as meaningful participants in a broader human community rather than as people who have been by acts outside their control cut off from it. "Radical relativity" and story telling cannot of course prevent events like tsunamis and hurricanes but they might serve as well as some antidote to the resulting trauma (cf Continuity and Catastrophe and Meeting Death With a Cool Heart). And a more general understanding of and commitment to "radical relativity" and story telling could at least lessen conflicts between humans and the associated traumas we cause each other (cf 11 September 2001. Perhaps an even more general application of Wittgenstein's "meaning derived in use" principle: that the meaning of "morality", "meaning", and "caring" themselves derive from (and are continually modified by) action?

Phew. Not sure that actually "tidies up", but maybe it does explain why I think "story telling" is important? and give us a possible way to relate my "I-function" and your proprioception/body art to it? In a way that opens some directions for further conversation about .... survival, animal/being, trauma, whatever? The "I-function" is, thanks to your pushing, alive again (nestled in the bosom of the story teller). Hope this is all at least somewhat useful to your story as well.

KS to PG, 26 December 2005 (see begining)

One month after your last exuberant, extended, and beautifully illustrated response, and following a wicked semester ending in flu, I am able to answer your commentary. I've divided my response into sections for easier reading.

Sports: Before I get started, you mentioned "game set" in your last response, suggesting that on some level you might experience our conversation as a kind of competition. Keeping in mind my maternal grandfather Dr. Frederick Rand Rogers' famous motto - "Tie score equals a perfect score" - let's remain with the conversation metaphor, which is more relaxed than a match.

Tidying Up: I'm afraid not. Your response was so rich with information, assertions, assumptions and so forth that the table is not only a mess but dominated by the "story teller" term, which rather than getting us closer to a discussion and understanding of proprioception in the humanities and sciences sends us spinning off into myriad fascinating directions, each of which need sorting out only to raise more questions and comments.

"Story Teller": Despite very careful consideration of your argument and a sincere effort to embrace this term, one that is obviously central to your worldview, "story teller" remains unconvincing to me as a philosophical concept and too imprecise as an intellectual construct to do the work that you want and need it to do. I have ruminated long on my problem with the conceptual apparatus of this term and have several points to add to those I've already submitted:

History: In addition to the fact that I still believe that your initial term "I-function" best captures the operations of proprioception, my apparent intransigence with regard to "story teller" reflects, no doubt, the fact that I am an historian. Yes, that old chestnut raises its contentious head again, and again, and ... . Indeed, our discussion - at base - is really between an academically trained "historian" and a "biologist" (who happen to specialize, respectively, in art and the nervous system). Too often it is forgotten that "historian" is a critical methodological position from which the "art historian" researches and writes. Being an historian is different from being a critic, although the two obviously can co-exist and, when they do, often conspire for the best result. But an historian must be responsible to evidence, whereas a critic may use interpretation without concern for evidentiary questions. In other words, a critic may rely on his/her "story teller" to make sense of political, social, economic, aesthetic, cultural, biological effects, and while an historian tells a story s/he must make certain that this "story teller" is responsible to exterior evidence/quanta. This is not to suggest that the critic may not also be concerned with evidence, but s/he is not required and expected to do this double duty and be so preoccupied.

The linguistic turn that culminated in the notion that language cannot relate to anything but itself posed a significant and important challenge to the notion of historical objectivity, a poststructuralist umbrella under which my scholarship matured in the midst of the historians' debates from Hayden White to Francis Fukuyama, even as I was trained in the traditional historical method: namely, I value close examination of documents; respect the need for questions of internal consistency, reliability and usefulness of sources; value painstaking attention to detail; and even as an historian of contemporary art, work in the archives of artists, and so on. While I do not claim that such practices and methods offer up Truth, with a capital T, as with science, a sound historical method prevents the kind of story telling of people like David Irving, a self-styled "historian" and Holocaust denier, from gaining authority that might have an historical impact. (On Irving see the eminent British historian Richard J. Evans Lying About Hitler [2001], a fascinating account of the law suit Irving brought - and lost - against the academically trained American historian Deborah Lipstadt and Penguin Books for her book Denying the Holocaust [1993], in which she cited Irving for his false claims and neo-Nazi ideology.)