Remote Ready Biology Learning Activities has 50 remote-ready activities, which work for either your classroom or remote teaching.

Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

| Emergent Systems 2005-2006 Forum |

Comments are posted in the order in which they are received, with earlier postings appearing first below on this page. To see the latest postings, click on "Go to last comment" below.

| "nothing is indifferent to the arrangement of its Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2005-09-07 15:50:02 Link to this Comment: 16022 |

Whoa! this is exciting--being the first to write on the new year's blank slate...

I want to thank Alan for this morning's useful response to a not-so-useful essay; for me, it provided a helpful

I would like further pulling apart of/application of the reductive method to

It also occurs to me that the instruction I got in last week's session, in the "five classes of indeterminacy," might also be helpful in teasing apart some of these distinctions. According to my notes, the created-on-the-spot catalogue included

| summing up (the parts) Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2005-09-14 19:06:13 Link to this Comment: 16142 |

So...what I got out of/picked up from this morning's search for a version of "the whole is no more than the sum of its parts" that is actually worth claiming/that some reductionist would find worth defending/that some emergenauts would find worth denying...

| abstracting emergence Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2005-09-21 11:37:03 Link to this Comment: 16237 |

It occurs to me that, rather than lament the fact that I seem to be holding a monologue here, I should just accept the role of archivist, recording what she finds useful of our weekly conversations, for herself and anyone else w/ an interest...

What interested me, in Rob's review this morning of Ernest Nagel's "The Reduction of Theories" (from The Structure of Science: Problems in the Logic of Scientific Explanation, 1961) were three distinctions (all of which--I think?--are isomorphic):

My question now, of course, has to do w/ the relation between each of the terms. I thought that emergence had to do with exploring those situations in which we can only understand the logical and structural relations between properties by playing them out temporally and historically, since what is distinctive about such systems is that the parts do not act independently of one another, that their interactions have consequences for both the whole and other parts that can not be known ahead of time. So I'm puzzled when Nagel says that temporal/historical emergents constitute a "problem of a different order" from those he calls logically unpredictable....Does a 'different order' just mean 'a different level'?

While I'm archiving/abstracting...not unrelated, I think, is a conversation nearby, regarding the "intervening" or "predictive" quality of what we know (="truth"?)

| closing the system, retrospectively Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2005-09-28 16:09:35 Link to this Comment: 16347 |

Of great interest to me this morning (for which many thanks, Tim), were three things:

I really, really have trouble with closed systems. On any level....

| firewalls and armor Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2005-10-01 10:54:45 Link to this Comment: 16405 |

...a very striking intersection took place this week (question is: is it an irreconcilable opposition?) between claims being made in this discussion about a useful response to Katrina including the building of a firewall, one that assures the safety of the whole by not allowing the contamination of a part to s-p-r-e-a-d...

and the (directly counter?) suggestion, in the forum for Stories of Teaching and Learning, that what we really need to do is not put on armor, but take off armor, and to open ourselves to others, which brings with it the possibility of being hurt (and changed)--

and overwhelmed.

| enlarging the local Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2005-10-05 15:54:14 Link to this Comment: 16454 |

what i'm interested in understanding better/knowing more about

(based on what i heard this morning)?

--if the usefulness of all stories is "local,"

--and the work of science is aiming for "wider" applications of the tales we tell--

| drawing the line @ tautology Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2005-10-19 18:46:13 Link to this Comment: 16550 |

Karen, you said this morning that you didn't understand what it meant to say "to call this 'truth' -- even 'relative' truth' -- is to hide the action of choice". Since that was me speaking (and since you didn't get an answer to your question), I'll presume to answer it here. What I meant was that we make choices to value certain stories, based on our core values, and to call a story the "truth," or even "relatively truthful," is to cover up the choice and the valuation. (This accords, of course, w/ the argument Paul was making today, that all stories express an authorial point of view.)

I found that argument quite convincing, along with its correlary, that science stories are useful because generative, and to be judged on the basis of their generativity. But I also found that argument--in this context--a particularly striking drawing of a line in the sand (more, actually: building of a wall...), a line which (I think) makes the argument tautological: if we value science because it creates the most generative stories, then we value the most generative stories. But on the other side of that line, outside that fort, there are other contexts, other worlds.

This summer, I heard a talk that juxtaposed three world views and their core values (a core value being "that which needs no further explanation"):

There are trade-offs in each view (in the modern world, for example, where science reigns, there exist difficulties in dealing with the nonquantifiable: "if it is not sense data, or derivable from that," then it is "non-sense," not real).

A concrete example:

Among a group of students returning from a semester abroad,

| representation vs. simulation--NOT Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2005-10-26 16:22:42 Link to this Comment: 16635 |

Thanks, Ted, for this morning's good talk on "emergent sustainability": I learned a lot, and find it particularly interesting (and heartening) to hear and think together about concrete applications for all our philosophizing. I was particularly intrigued by your presentation of Gonzalo Frasca's work on "ludology," his notion that, in games, going through "several iterations of a story is... a requirement....Games are not isolated experiences: we recognize them as games because we know we can always start over." I like this, and appreciated the particular application you gave, of the way in which such simulations led to a solution in the conflict between Senegalese herders and farmers.

One point of disagreement and (I hope) correction? You describe Frasca as contrasting this sort of "simulational" activity with the "representational" work of "traditional narrative," which "deals with endings in a binary way....Narrative authors...have only have one shot in their gun -- a fixed sequence of events....traditional narrative media lacks the 'feature' of allowing modifications to the stories."

Well, no. When I worked through an essay for the Emergence group a few months ago on "Literature and Literary Theory as Forms of Exploration", I argued that the

use-value of literary criticism, of the literature it interprets, and of language more generally, emerges in the moments where negotiation is necessary....Each time a new story is told, it identifies--in ways that are unpredictable beforehand--other tales not yet articulated. New stories get generated in an emergent process, as interactions in the environment leave traces (in literature) that are continuously picked up (in literary theory) and re-combined in new configurations. Literary analysis makes new stories out of the stories we have preserved; the most useful of those are continuously generative of that which surprises.

So: a concrete example? Two years ago, when Paul and I offered the first iteration of our course on The Story of Evolution and the Evolution of Stories, very different meanings of the same passage emerged in his section and in mine. At the very end of Moby-Dick, Ishmael describes himself as endlessly the shipwreck: Round and round, then, and ever contracting towards the button-like black bubble at the axis of that slowly wheeling circle, like another Ixion I did revolve. Led by biology? Buddha? Paul?, his group read this final scene as peaceful, accepting, even "zen-like"; led by me--and what I know of Ixion (the first human to shed kindred blood, bound to a flaming wheel as one of the more famous sinners on display on Tartarus) my group arrived at, well

The point(s) here (as per the literary critic Jonathan Culler) is that "Meaning is context-bound, and context is boundless; there is no determining in advance what might count as relevant." It's always negotiable, always revisable. In other words, traditional narrative--as it is taught using reader-response theory--is always open to "repetition," "simulation" and new "interpretations" that arise thereby. We, too, are always playing games.

| lit crit Name: Ted Date: 2005-10-26 17:46:15 Link to this Comment: 16637 |

| firewalling emergent disaster Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2005-10-30 09:31:25 Link to this Comment: 16697 |

Looping back for a moment, past more recent discussions of emergent sustainability to an earlier one about managing emergent disasters... The Chronicle ran a piece recently (10/7/05) looking @ the organizational breakdown during and post-Katrina:

It was a mistake...for the Federal Emergency Management Agency to be folded into the department of Homeland Security...small agencies...do not mix well with...the "gun-toting" culture of the intelligence and law-enforcement agencies....they have a propensity to have small groups of loyalists in a room making decisions, closed off from every one else....the department is hamstrung by a "command and "control" mentality that is ill-suited to the realities of disasters...."in a disaster, decisions are made at lower levels than they are made normally....the idea that anyone at the top could command and control all this activity is idiotic."

What struck me in this article was the claim that the habits of mind cultivated by military and law-enforcement personnel--their "command-and- control model"--are said to arise from experiences in dealing with an intelligent adversary. So they want to keep information secret....But emergency managers and medical personnel want information shared as widely as possible, because they have to rely on persuasion to get people to cooperate. Yet you may remember that what came out of our discussion a month ago was precisely the opposite suggestion: that, in looking for a way to manage such disasters, we build firewalls to minimize the positive feedback that can fuel catastrophe.

| Community as a complex system that displays emerge Name: Asher Date: 2005-11-06 13:20:10 Link to this Comment: 16827 |

| planning/not/both/and? Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2005-11-07 17:22:31 Link to this Comment: 16861 |

Hi, Asher. Nice to have you come by, recall us to some on-the-ground questions.

You might look both @ Christopher Alexander's

now-classic 1965 essay, "A City is not a Tree" (which starts with the observation that planned cities don't work), and @ a local example of thoughtful city planning @ the 40th Street Community Forum. Another relevent essay--about the need for top-down planning in political structures, when the bottom-up stuff isn't working, is Social-Political Structures: Academic and Biological.

| Science as a Category Name: Doug Blank Date: 2005-11-09 15:22:10 Link to this Comment: 16892 |

I appreciate Paul's attempt this morning to make a distinction between science and non-science by building on something concrete, if personal.

One test that has been in the backs of our collective mind has been the Dover, PA Intelligent Design trial. Could Paul's distinctions be used there to make a clear separation between these two stories?

Maybe a more important test was one that occurred a few years ago and had Stephen Jay Gould hopping mad. You may remember that some doctors had replaced the heart of a boy with one from, I believe, an orangutan. Gould suggested that if the doctor's respected the story of evolution (and related stories, such as genetic distance), then they would have been looking at chimps rather than a primate rather removed from the human branch of the tree. (I can't find the story any where on-line, but I remember Gould showing a picture of the child's tombstone and mentioning the doctors by name. This caused quite a stir at the Cognitive Science meeting.) Do we have a chance of making a distinction that would outlaw such actions?

If we live in a world where science can't be separated from non-science then we may be entering another Dark Age. Dark may be the way to go with rising fuel costs...

| the "truth" of story variety Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2005-11-10 22:51:27 Link to this Comment: 16924 |

I'm not especially interested in policing the distinction between scientific and non-scientific stories. (Partly because it's the varieties of stories science tells that interest me--ref. today's talk by Prof. Laszlo on "A Tale of Two Sciences: Physics and Chemistry," comparing the "visually literate" to the "mathematically literate," the differing/equally necessary and useful world views of those doing "conceptual analysis" w/ those engaged in hands-on "craft.")

And I'm not sure that the big log Tim threw on the track yesterday morning really stopped the train: the observation that "we can't use truth as a guide" is the "one true statement in the room (and so inadmissable by its own standards) is nicely sidestepped by the acknowledgement that this claim is just a well-placed "bet," a starting place that acknowledges that it well might not be true.

I'm also prepared to grant that the usefulness of all stories is "local," and that science aims to "extend the local," to offer "wider" applications of the tales we tell. But I still think there needs some clearer measure of what counts for "generativity" than a personal preference for certain kinds of stories--

and look forward to some concrete examples, next week, of the same.

| I am, therefore I want Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2005-11-10 23:03:47 Link to this Comment: 16925 |

While I'm listing areas for further discussion, I want to add an idea I picked up from the NYTimes book review this past weekend (11/6/05), entitled "I Am, Therefore I Want." The review describes a new book On Desire: Why We Want What We Want, which looks at the "desire-generating systems" of our brains, "a dominant verbal system that produces 'rational' (instrumental) desires and--perhaps more important--rationalizes those desires that arise from other, unconscious systems...all hankerings are nimbly enabled by an articulate mechanism that evolved to protect our species from the kind of internal conflict that would trip up a thriving, procreating and surviving fittest."

This seems to me a very different story than the one currently on the table, that it is our thinking/rationalizing which creates the conflicts, that the unconscious can settle those difficult questions with many variables which consciousness can't seem to sort out, that we don't need those "moments of absolutist discrimination," but might well do better to let the "gut guide us."

| insights and questions Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2005-11-17 11:15:28 Link to this Comment: 17047 |

Gratitude, as per usual, for yesterday morning's provocations. Two insights for me, one from the very beginning, the other from the very end, of the presentation:

I'm as thankful for the second list (of questions) as I am for the first (of answers). Gratitude, "really."

| "Swarm": teaching emergence in an art museum Name: Shir Ly Ca Date: 2005-12-09 13:52:08 Link to this Comment: 17360 |

The Fabric Workshop and Museum (FWM), a contemporary art museum in Philadelphia (www.fabricworkshopandmuseum.org), is currently putting together an exhibition entitled Swarm. The exhibition will feature contemporary artists who have engaged the concepts of collective intelligence, self-organization and emergence in a variety of ways. Some of the artists, including Paul Pfeiffer and Yukinori Yanagi, directly address bee and ant swarms, while others, like Matthew Ritchie and Julie Mehretu, approach the idea more broadly or abstractly, looking at collective intelligence in cities, software and on the Internet.

This exhibition has been organized br FWM and guest-curators Abbott Miller and Ellen Lutpon. Swarm explores contemporary works of art through the social and scientific lens of emergence. The contemporary artists selected for Swarm explore and engage the phenomena of emergence though a variety of media, and represent a diverse cross-section of cultural and geographical contexts. Works emphasize "swarming" as a social effect generated by masses of objects, images, data, or organisms, reflecting a contemporary view of nature, politics, and social life.

SHIR LY CAMIN

Education Coordinator

shirly@fabricworkshopandmuseum.org

215-568-1111 x14

The Fabric Workshop and Museum

1315 Cherry Street, 5th Floor

Philadelphia, PA 19107

www.fabricworkshopandmuseum.org

p: 215.568.1111/f: 215.568.8211

| the art of emergence Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2005-12-09 13:53:54 Link to this Comment: 17361 |

Shir Ly--

thanks again for coming out this morning--I very much enjoyed hearing

about the "swarm" exhibit, and thinking together with you about ways such art

might be used to engage and "teach" scientific concepts like emergence to

varieties of students (both young and old).

In hopes that we will continue to be in touch--

I'd be delighted to find a way (for instance) to archive images from

this exhibit on Serendip, for use in future courses.

Anne

| giving the exhibition some (after) life? Name: Shi Ly Cam Date: 2005-12-09 13:56:59 Link to this Comment: 17362 |

Hi Anne,

It was great to meet you all! I was reminded of why I love my job – I get to learn so much about everything that informs art and connect with people thinking about those varied ideas. I truly look forward to learning more about emergence, how it fits into so many varied disciplines and how to use the exhibition to connect with others on such varied levels.

...We’re applying for a grant from the Pennsylvania Humanities Council (PHC). The grant would fund an interdisciplinary panel discussion at the close of the exhibition... if someone would be interested in helping us persue this.

I will contact the curators regarding giving the exhibition some life, perhaps on Serendip, past the duration of the show. I thinks it’s a great idea and am sure the curators and artists would be thrilled to know that their work is relevant.

And, lastly, I want to re-invite you to have one of your meetings here. We could either open early for you or close late if it’s easier for you to come after classes.

Let’s be in touch.

Best,

Shir Ly

| beyond appiah ... Name: Paul Grobstein Date: 2005-12-14 10:59:34 Link to this Comment: 17394 |

On other fronts .... is interesting idea that one AT THE MOMENT needs to pendulum swing back toward the individual and within the individual to acknowledge the importance not solely on the "rational" nor the "intuitive" but the combination of both (see Writing Descartes ... . The "at the moment" is an acknowledgement that all ethical/moral thinking is "in progress", ie that at another time and place the need to get it "less wrong" would require re-emphasizing the significance of collective stories.

| leaving a crack for fresh air to get in Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2005-12-14 12:10:28 Link to this Comment: 17396 |

I'm grateful, too, for the conversation extending from/provoked by my report on/quarrel w/ Appiah this morning. I found quite valuable Sandy's contributions regarding "the problem of public facts" (in particular, the self-fulfilling prophecy of the "taxi driver thought experiment" regarding racial profiling, which so resembles our earlier discussion regarding the need to "dampen" the positive feedback that generates catastrophe).

And/but: I'm not @ all ready to acknowledge that moral thinking needs (ever) to emphasize individual over collective stories; the loop between these two sorts of story-making--that arising from personal experience, and that arising from story-extending and comparing--needs to be every bit as on-going and insistent as that between the intuitive and the rational.

Along those lines...I'm hoping that, in the new year, the emergence group might attend more to this sort of social-science-y angle on the world: how we might most usefully construct communities that facilitate the emergence of what is new?

In the interim: emergenauts might be amused to read a fairy tale, collectively written by the students in my college seminar, in which--when outsiders are admitted--a "crack" for revision appears in stale air of the Bryn Mawr bubble.

| nitpicking of the masses Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-01-20 15:18:45 Link to this Comment: 17706 |

So, I've been rolling over in my mind what I heard from Mark on Wednesday morning, trying to see if I find it "true" or @ least "useful." Here--for my own clarification & for whatever use it may serve to others--is where I've gotten so far.

Mark's description of Misinformation Networks started (and stayed) with the presumption that true information is clearly distinguishable from misinformation. Since for postmodern me it's "stories all the way down" (with every story motivated and shaped by the investments of the storyteller, however unconscious she may be of them), I got hung up on that initial distinction. That made some of the later claims (that the "technology of slant," for instance, involves "omitting information") not quite compelling for me, since (for instance) I'm quite sure we never have complete information. By Mark's definition (and my lights), every story is "slanted": that is, just a slice of all that is, and necessarily a slice that reflects the "angle" of the slicer.

I found Paul's contrast between the "google" and the "wikipedia" models a handy one (i.e.: the usefulness-of-knowing-what-more-people-value, vs. getting-@-the-truth-by-increasing-the-number-of-watchdogs). But I also think there's a third (non-binary/non-binding) option. I got a glimpse of this @ a talk I heard last spring, which juxtaposed three world views and their core values (a core value being "that which needs no further explanation"):

A concrete example:

Among a group of students returning from a semester abroad,

science in the long run gets most things right - or, as Paul Grobstein, a biologist, puts it, "progressively less wrong." Falsities pose no great problem. Science will out them and move on.

What became startingly clear to me, during Mark's presentation, is how very different that description of scientific method is from the phenomenon he was describing: the inclination of human beings to seek--not what will expand their knowledge base, not what is new and different from what they already know--but rather simply confirmation for what they already believe.

So (punch line)--I guess I just don't buy it:

more wrong. (In saying that, I'm well aware that I am revealing my own strong investment in/hope for learning new things.)

;)

| Pre-suppositions of the Pre-postmodern Name: Mark Kuper Date: 2006-01-23 13:53:15 Link to this Comment: 17749 |

| truthiness Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-01-26 23:15:21 Link to this Comment: 17820 |

(My subject line comes from mock Comedy Central pundit Stephen Colbert, whose "slinging of the world 'truthiness'"--the NYTimes says--"caught on instaneously last year precisely because we live in the age of truthiness," when "what matters most is whether a story can be sold as truth.")

I know better than to speak for Paul, but will just say (as preface to what I really have to say) that--in the spectrum of the postmodern--I am distinguished by representing 1) the tragic view, 2) one that recognizes no progress, and 3) the one most invested in the communal/ the construction of the collective (it's an interesting question whether 1) and 2) are the effect of 3), but that's for me and my analyst, not for this space...)

I do think Mark exaggerates the perils of my perspective; one can see all stories as constructed, as not grounded in or accountable to an "objective reality," and still be able--in fact, be compelled--to make valid distinctions among them; for a strong argument in this regard, see On Beyond Post-Modernism: Discriminating Stories. But since it's pretty clear that neither of us is going to argue the other out of his/her particular angle on the nature of the world, I'd suggest that, given those differences,

it might be more productive to see where keeping both (or 3, or 10--everyone else is welcome to come join!) angles of vision in play--and rubbing up against one another--might take us...

So, here's my first move in Mark's direction: I've just finished reading an essay by Mike Tratner, a colleague in the English Department, called "Derrida's Debt to Milton Friedman" (New Literary History 34, 3 (Autumn 2003): 791-805. Michael goes so far as to argue that the emergence of deconstruction and postmodern ways of thinking were shaped by the changes in everyday economics and governmental practices of the 1970s:

Milton Friedman argues that money...is a system for distributing signifiers which have no referent...a 'social convention that owes its very existence to the mutual acceptance of... a fiction'....the fictionality of money became evident...as the value--or the 'meaning'--of monetary signs began fluctuating daily....The fictionality of money became an important economic tenet of governments and a commonplace of newspaper headlines declaring the latest inflation figures....

This all seems to be quite evocative of/directly relevant to further elaboration of the very interesting presentation by Laura Blankenship last Wednesday morning, in which we explored together the playful?/transgressive?/immoral? activity of googlebombing, the work of pranksters who "interpret" sites through their own particular frameworks (wherein Bush becomes a "miserable failure," etc), rather than grabbing directly, w/out translation, words from the sites themselves. But I would say that this sort of interpretation is what all of us are doing all the time: when we decide what data to collect, when we decide how to represent it in a graph or an image or a certain set of words. It is stories all the way down: not just the explanation of the facts, but the facts themselves are constructed. If this is the way the world (and our movement through and management of the world) works, then what is key is our intention: to what use are we putting our stories?

My daughter has this great quote from John Steinbeck's East of Eden) hanging on her bedroom wall; it offers one way of distinguishing among stories:

I think the difference between a lie and a story is that a story utilizes the trappings and appearance of truth for the interest of the listener as well as of the teller. A story has in it neiher gain or loss. But a lie is a device for profit or escape.

| the gift that keeps on giving Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-01-27 17:16:10 Link to this Comment: 17823 |

So--that was the anecdotal warm-up. What I was working my way towards (and here's the punch line) is a postulation/question that might shift our focus from the opposition we developed over the past two weeks, between truth and lies, to a discussion of what difference it makes if we conceive of our object of study (the world, or any slice of it--economic, literary, biological, etc.) as an open system. (My thinking about this goes all the way back to that summer of very-interesting inquiry into Information.) What I re-discovered, in reading Michael's article about Derrida and Friedman, was Derrida's essay on "The Gift," and its claim that gifts (like credit! like going off the gold standard!) unsettle closed systems. They don't expect exchange or reciprocity (needed in a closed system, where energy cannot be lost) but rather bring in from outside something NEW, stringlessly, without expectation of return.

How helpful is THAT?

Emergently,

| meta-meta--and beyond Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-02-01 13:50:14 Link to this Comment: 17914 |

My questions this week--arising from Sandy's lit review, this morning, of social scientists who are using an emergent framework to think about issues of inequality--are really meta-meta (so I'm unsure if I can really articulate them or if--having tried to do so--anyone can understand me). But: nothing ventured, nothing gained. So here goes (straight to the mountaintop):

I am VERY intrigued by this possibility--and/ but somewhat unsure about how to pursue it....help?

| Emergence and Feminism Name: Laura Date: 2006-02-03 08:39:47 Link to this Comment: 17948 |

| Re: Emergence and Feminism Name: Lisa Date: 2006-02-05 23:30:38 Link to this Comment: 17981 |

| Can we manipulate emergent phenomenon? Name: Doug Blank Date: 2006-02-06 09:55:48 Link to this Comment: 17986 |

Very interesting discussions already this semester! One common thread, perhaps, is: can we manipulate emergence? This is also related to last semester's discussion "Emergence in emergencies" on hurricane Katrina, and George Lakoff's talk on use of language.

Sandy discussed an attempt to manipulate emergent systems through policy, and that was seen to work somewhat. But the system largely resisted the attempt and showed robustness and stability to remain in place.

Laura showed us the blogosphere, and demonstrated "google bombs", grassroots, coordinated, distributed, conscious attempts to create a "tipping point".

When a company tries to trick the system into giving its product pages a higher ranking, they call it "webspam". Matt Cutts is the Google employee responsible for the webspammers. Recently, he wrote in his blog about a recent example by BMW. He discusses the rules, and how they broke them. Here is an article also about it.

Mark's discussion explored how one could fashion a message to be easily digested, and passed around in an emergent system. It seemed to work pretty well.

All of this reminds me of an analogy I think of often: imagine yourself as a neuron, attempting to get your fellow nodes to fire. It may be that we can manipulate the system, but not directly through policy. We may have to make very subtle movements with items that don't appear to have much to do with the topic of interest. For example, what to do about inequalities in gender value? Maybe we just need to wear red. Or talk softly. Or refer to pickles often. The point is that it is an emergent system, and we have to manipulate it at that level.

Maybe if we get our fellow neurons to, say, laugh, that might cause a spread of a little dopamine, and they'll fire at will. Think emergently.

| emerging parenting Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-02-07 13:11:06 Link to this Comment: 18008 |

I was struck--surprised--by Laura's invitation to us to think about the "failure of feminism" (i.e. women ending up @ home w/ the kids) as an emergent phenomena--since I have come to think of emergence as a principle that enables change (see, for instance, my quarrel w/ Appiah: "the duty of [wo]man is...in respect to [her] own nature...not to follow but to amend it").

The sort of analysis Laura sent us to, such as the piece on America's Stay-at Home Feminists, which describes women who think they are "voluntarily taking themselves out of the elite job competition" under the assumption that they are 'choosing' their gendered lives," actually seems to be strongly anti-emergent in both its presumptions and its prescription (i.e., it argues for a linear single-causal intervention: "find the money," use your "college education with an eye to career goals," etc. etc.)

Consider, alternatively (emergently?) the question that has come up repeatedly in a series of conversations on Representing Parenting, being held on Friday afternoons this year over @ the Multicultural Center on the Bryn Mawr campus: Why/how has the work culture in this country become too deeply entrenched to create a space to mother?

Anyhow, if you'd like to talk some more about this-and-related issues--i.e., to take what Lisa calls a "descriptive rather than normative" approach: asking not just "how emergent phenomena work," but how to "modify these workings to produce a different result," come to the next of these events, being held @ the end of this week:

Can Women Have It All?

And What Role does Public Policy Play?

A Study of Bryn Mawr Alumnae in the Federal Civil Service

Can women "have it all?" Based on interviews with Bryn Mawr alumnae

in the federal civil service, Marissa Golden can answer, "kind of."

She found that these women work in meaningful and rewarding jobs and

feel that they spend enough time with their kids but that they have

almost all taken themselves off the career "fast track." In a talk

this Friday, Marissa will discuss the competing goals that

"family-friendly" workplace policies are designed to achieve and how

these policies help in the attainment of some of these goals but not

others. She will also make an argument for why she thinks it is so

important to get at least some of these women back on the "fast

track" but why she also thinks that our public policies need to do

more to improve the well-being of the children of these working moms.

Please join us for this talk, this Friday, February 10,

2:30-4pm in the Multicultural Center.

Drinks and snacks provided.

Fifth in a series on "Re-presenting Parenting,"

co-sponsored by the Program in Gender and Sexuality

and the Center for Science in Society:

http://serendipstudio.org/local/scisoc/reparenting.html

| emerging emergence ... Name: Paul Grobstein Date: 2006-02-11 10:12:04 Link to this Comment: 18064 |

| More on parenting Name: Laura Date: 2006-02-11 10:55:15 Link to this Comment: 18065 |

Name: Date: 2006-02-11 11:08:07 Link to this Comment: 18066 |

| for Sandy and Mark Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-02-18 10:58:28 Link to this Comment: 18187 |

"Thinning the Milk Does Not Mean Thinning the Child," NYTimes (2/12/06): "skeptics say they are not surprised that, even with studies showing the ineffectiveness of intervention...communities continue to mandate those same changes. Scientists and the public...'have this wonderful capacity for ignoring negative evidence.'"

| for all Name: Paul Grobstein Date: 2006-02-18 15:33:22 Link to this Comment: 18192 |

| conflict in non-normal inquiry Name: Date: 2006-02-18 16:01:12 Link to this Comment: 18193 |

| right understanding--for now? Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-02-22 17:43:35 Link to this Comment: 18291 |

What a pleasure, exploring with y'all way beyond cluelessness this morning. Thanks for interest/prodding/further thoughts-and-questions. 'Til the next round, I'm bookmarking these notes:

On to revolution. Stay tuned.

| & on beyond social science Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-02-22 18:17:37 Link to this Comment: 18293 |

(In the meantime, should anyone be pursuing a career, a publishable idea, or a richer conversational life:) here's a relevant call for papers for a new peer-reviewed journal on Emergent Anthropologies, which welcomes "responses to ideas of 'emergence' and 'anthropology' in its broadest sense."

| dismal science Name: Sandy Schr Date: 2006-02-23 10:11:44 Link to this Comment: 18311 |

| Re: on beyond cluelessness Name: Al Albano Date: 2006-02-23 20:24:28 Link to this Comment: 18317 |

*"what would happen if you substituted for the contrast between open and closed systems the (less binary) distinction between binary and continuous systems?" (do I understand you aright, Al? thinking like a physicist means re-conceptualizing the social, as the natural, world in terms of multiple variables, not easily reducible/clearly separable into 0/1, off/on, up/down?)

There are some physical variables that can take on only one of two values (yes or no, zero or one); there are others that can take on a full range of values (from some smallest value to a largest value, with all values in between possible). Was your point that sexuality/gender need not be represented by a variable that can take only two values, but rather by one that can take on all values from one extreme to the other? a continuous range of grays from white to black?

* "although the closed system is a very important concept in physics--i.e., the amount of available energy does not change--shifting the scale opens up possibilities" (do I understand you aright, again, Al? "all physics is local"; subsystems may be open "enough" for our purposes)

I'd say say so, but with some caveats. I'll take at least an hour in March to try to explain what I mean by that!. No system is truly isolated. Our universe probably is (Is our universe the only one there is? If not, then it may not be global, either!)

* "but you can't really consider utility a subset of physics" (I'm not sure I understood you, Ronni--did you mean that it's 'way too glib/easy to use energy as a measure for social change?)

I thought more about this afterwards and I'm still not sure I know what I'm talking about -- Of course, physics has nothing to say about things like utility, meaning, value. When we deal with human/social questions and use physics as a metaphor, we the "story tellers" introduce these notions and make them part of the story we tell. But these did not come from physics.

* "let's question the presumption that it's a good thing to have more (rather than less) people engaged in any project--as well as the further presumption that involving more people introduces more flexibility and fluidity into the system" ...

When you were discussing this, I kept thinking of Emmy Noether, who taught

mathematics at BMC in the 1930's. She did a whole slew of brilliant

mathematics under very adverse anti-feminist and anti-semitic conditions

in Germany (I think she should really be a feminist icon!) but among

physicists, she is well-known for just one theorem (called Noether's

theorem, what else?). It applies to a very narrowly-defined mathematical

context, but some 15 years ago, I took some liberties with it and came up

with the following: "if you have a theory about the way a system behaves,

and if the mathematical form of your theory does not change even if you

change your point of view, then there exists in that theory a quantity

whose value will characterize the system forever. In effect, what

Noether's theorem says is that concepts which do not lose their integrity

and their attractiveness even when considered from different points of

view are invariably linked with values which are of lasting importance..."

But is that putting too much value on consensus?

| without further embellishment Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-02-24 07:24:53 Link to this Comment: 18324 |

And now totally out in left field...

I've been spending some time, lately, engaged in (and of course reading about!) a variety of Buddhist meditation practices. Early this morning I came upon this phrase, in Pema Chodron's When Things Fall Apart:

"Meditation is probably the only activity that doesn't add anything to the picture. Everything is allowed to come and go without further embellishment....Not filling the space... provides the basis for real change."

Anyone else see a connection, here, with this week's conversation about moving in the direction of positive social change through a process of non-normal inquiry? I'm referring, first, to the exercise of not forcing things to happen/events to evolve, but allowing them to, as they inevitably will. But I'm also gesturing (I think...) to something much deeper, something which nibbles @ Paul's observation that finally, economics' expansionist premises will need to come face-to-face w/ the laws of closed-energy physics: that not adding anything...

is the only way to add anything.

| Markets Name: Mark Kuper Date: 2006-02-27 17:23:23 Link to this Comment: 18370 |

* "markets are always a positive-sum game" (do I understand you aright, Mark? thinking like an economist means presuming NOT mere re-distribution of resources w/in a closed system, but actually generating new resources of production?)

This is actually a little complicated:

1) One can think like an economist with respect to the "mere re-distribution of resources" and with respect to "generating new resources". Different, more complex issues, arise when "generating new resources", but fundamental economic thinking applies to both.

2) With respect to the "re-distribution of resources", this is not Always a positive sum game.

a) A deep insight of economics is that even with a fixed amount of resources there can still be improvements in everyone's utility (we call these "pareto improvements" after the late 19th/early 20th century Italian economist/sociologist Vilfredo Pareto who formalized the definition of economic efficiency that we use today). So, if we randomly distribute a fixed amount of goods among a lot of people, they can ALL be made better off (or at least not worse off) if we allow them to trade. So, what may appear as a zero sum game really isn't (this is what I was emphasizing in my remarks to Paul). This is one strong justification for markets.

b) But, once all of the pareto improving trades have occurred, so no one has any desire to trade what he/she has with anyone else, we ARE in a zero sum situation: we can only improve the utility of one person by taking utility away from someone else. Put another way, the process of getting to an efficient allocation of resources can be a positive sum game - this is what voluntary trade is. (Parenthetically, you can, however, get to an efficient allocation of resources in other ways that are not pareto improving). Once you are at an efficient allocation, you are in a zero sum game.

c) For the advanced students amongst us, there is one caveat to the above. Competitive markets determine prices and as large numbers of consumers or producers change what they do, these prices can change. These price changes can hurt people. So, for example, if China buys up a big part of the world's concrete, concrete prices will rise. Americans who are buying concrete will be worse off than if China had not entered the market, so the price movements themselves are not positive sum games - they create winners and losers. Still, if at any given moment, I decide to buy concrete, I am better off conducting that transaction than I would be trying to make the concrete myself (otherwise, I would not be in the market).

3) "we never have perfect information; gains in trade are never guaranteed". This is, of course, true, but the question is:

How often does it happen that we make a trade that we regret, in comparison to the sum total of all trades that we make? I say this because the alternative seems to be to close down markets and have no trades (since we cannot in advance know which trades we will not regret).

4) "there is an essential interface between economics and physics: the former assumes that expansion is good; the latter acknowledges that resources are limited" WRONG Economics is ALL about scarcity. If there was no scarcity, there would be no subject called economics. We are all about making decisions subject to constraints. Optimization subject to constraints is the heart of economics.

| on beyond cluelessness Name: Wil Frankl Date: 2006-02-27 17:25:22 Link to this Comment: 18371 |

Upon reading Al's and Mark's responses I am curious about how hierarchical/scalar analysis applies to defining open versus closed systems.

Economics particularly interests me as I admit I know little of... At what temporal scale is value determined in markets? At what temporal scale is utility determined? Per Al, open vs closed systems might be better qualified as how proximate or distal/ultimate you define your system. If this idea is applied generally to economics, then value of trade/markets, utility of trade/markets is altered by the scope of the system defined. Thus, valuing immediate capital gains at the expense of long term sustainability seems to be an arena that could benefit from our sliding scale "emergent-y" analysis (hierarchical analysis).

I would like to explore whether or not there exists useful universals/rules that apply to sliding the scope of systems towards the open end of the spectrum versus the closed end of the spectrum (maybe narrowly defined systems versus broadly defined systems helps here). If I understand Anne correctly, she is suggesting that opening up Gender Studies will be beneficial--more agents, more engagement, more diversity, more generativity. But does opening the system always create more value/utility/generativity? Or is there a limit? If so, are there any general principles to help choose a boundary? Per Mark, limits apply in economics after "pareto improvements" have been maximized. (Vilfredo Pareto is an exquisite name). If no general rules apply, exploring the limits within the gender system has been very provocative, digital images not withstanding. Thanks, Anne.

| opening/closing the emergent system Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-02-27 17:31:04 Link to this Comment: 18372 |

So what strikes me here is that we've got ourselves

| Public Forum at The Fabric Workshop and Museum Name: Date: 2006-03-01 14:20:07 Link to this Comment: 18415 |

| Biting the bitten bullet ... Name: Paul Grobstein Date: 2006-03-01 14:29:30 Link to this Comment: 18416 |

So here's the rub in Ronni's story (for me at least). One can use emergence as a way to get to a particular place, ie not tell people what you're trying to get them to do collectively but instead give them properties/circumstances that will by virtue of their interactions cause them to get there. Alternatively, one can commit oneself firmly to the proposition that emergence is a process whose function is as much to discover/create new places to be (in perpetuity) as it is to get to any particular place. All other things being equal, the latter it seems to me requires one to act in ways that maximize the generative capabilities (and hence likely differences) of individual humans since that in turn maximizes the variety of places being conceived/explored by the society/culture.

Ronni's setting her story in the context of pragmatism and evolving morality took us a long ways in that direction but ... then there was the bitten bullet: roughly "I don't care how or why people believe in the symmetry principle but only that they do so". And here I think I'm on Ronni's roomate's side, at least as far as the theory is concerned (more on the issue of practice below). I share Ronni's sense that the "symmetry" argument is an important one for people to be aware of but I'm disinclined to hang it entirely on an argument about "social good" and still more disinclined to try and get people to "believe" it without question.

The problem with hanging the argument on "social good" is, of course, that different people have different conceptions both of what "social good" consists of and about how to get there (including what tradeoffs between ideals and practices/politics are appropriate). And while some of these differences may be such that large numbers of people agree on one rather than another ("nazism"), there remain differences between people that are .... differences within the community of "reasonable" people. The upshot is that "social good" won't itself provide a reasonable basis for adjudication among alternatives.

More importantly, any effort to get all people to believe anything without question itself provokes .... question. And conflict. This is a big problem (a "bug") if one wants to achieve a particular social outcome but perhaps more of a positive (and hence a "feature") if one is thinking of emergence and an ethics thereof. That people "question" and therefore are inclined to think of alternatives to those presented to them is, all things being equal, a desirable characteristic if one is commited to emergence as the ongoing exploration of novelty (and perhaps even if one is committed to the "social good" by narrower definitions; having individuals think for themselves is a not bad strategy for businesses, for example to discover new and improved ways to do things, and so to compete successfully in the marketplace).

So, what about the "tragedy of the commons" (and a whole variety of similar cases)? How does ond deal with the situation where most people have only local information and so act in particular ways, and someone who happens to have a broader view sees a different way for everyone to act that would get everyone more of what they want? How should that person act? Must they give up the commitment to emergence? In the interests of the "social good"? In the interests of emergence?

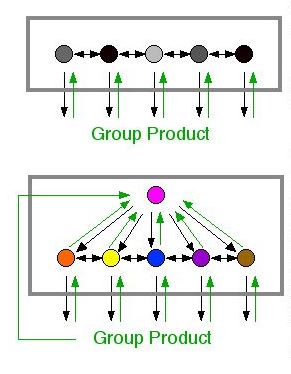

That person in that situation is the "non-normal" inquirer (also known as the truly effective therapist/teacher/parent/lawyer/social activist, aka the fuschia dot). That person knows they have a "less wrong" story than any other stories floating around, but also knows there exist as yet untold still less wrong stories, that getting to them depends on the diversity of stories in play and that that in turn depends on people developing their own skills as independent inquirers/story tellers.

What this suggests is that the primary commitment of the "non-normal" inquirer, of the emergentist (and all of those other things) has to be to the process of inquiry/emergence itself rather than to any particular outcome, and so they must act in ways that preserve, indeed enhance inquiry/emergence of what has not yet been. All other things being equal, this precludes their trying to get people to "believe" things and certainly precludes their discouraging people from doing their own questioning. In short, I think the emergentist has no sound moral position except to function as an educator: to tell his/her story, as clearly as possible, while listening to and encouraging others to do the same, and to trust that the dynamic interaction among stories will make appropriate use of one's own story and others in the ongoing process of the emergence of ideas/stories.

"All other things being equal"? Emergentism, and story telling, is of course derivitive of and contingent upon life. I can imagine circumstances in which the need to preserve life (one's own or that of others) overrode the requirement to educate, to facilitate inquiry/story telling. Even here, however, the moral argument is the same: as an emergentist one's obligation is to protect/enourage/support emergence/inquiry, all that which is necessary for the discovery/creation of what has not yet been.

Its in and from the bumping of stories against one another than new ones emerge. Many thanks to Ronni for a story (including the bitten bullet) that triggered this one. I hope mine in turn might provoke some further new stories form others.

| deliberately introducing a-symmetry Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-03-01 17:06:31 Link to this Comment: 18418 |

Very provocative, Ronni-- very important, and very, very brave. So--what you've got me wrestling with/provoked me to? A strong resistance both to

Besides?

| a-symmetry continued: none of us are exceptions Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-03-03 07:48:34 Link to this Comment: 18442 |

I'm still mulling over this matter of a-symmetry, still thinking through possible alternatives to acknowledging that one's self is not an exception, that we need to grant the same freedom of choice (and the same irrational unpredictable behavior!) to others that we grant to ourselves. Am put in mind of Rabbi Hillel's version of the Golden Rule: "Do not do unto others as you would not have done unto you." As noted in Karen Armstrong's The Spiral Staircase, "Hillel's version is better than Jesus'...it takes more discipline to refrain from doing harm to others. It's easier to be a do-gooder and project your needs and desires onto other people....when they might need something quite different."

| Replying to Anne's comment on the Golden Rule: Name: Lisa Benso Date: 2006-03-14 03:35:20 Link to this Comment: 18515 |

| Tomorrow's Meeting Name: Doug Blank Date: 2006-03-14 11:27:52 Link to this Comment: 18520 |

The Emergence Group will again meet tomorrow (Wednesday) March 15, 8am in Park Science 230. All are welcome; muffins, coffee, and scones provided.

Rich Wicentowski will lead the discussion on:

Knowledge-Free Induction of Inflectional Morphology

When we last met, we looked at a (questionably) emergent way of discovering the morphology of a written language. I presented examples from research I've done. Though we didn't get through all of it, I think you got enough of a flavor of it that we don't need to try and finish it up (though we could if you really want).

I'll present some research that takes a different approach to the same problem. If you want to get a head start, you can take a look at these papers:

Schone, P. and Jurafsky, D., 2000. Knowledge-Free Induction Of Morphology Using Latent Semantic Analysis. Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning and of the 2nd Learning Language in Logic Workshop.

On-line: http://web.cs.swarthmore.edu/~richardw/emergence/2006-03-15/W00-0712.pdf

Schone, P. and Jurafsky, D., 2001. Knowledge-Free Induction Of Inflectional Morphologies. Proceedings of the 2nd Meeting of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics.

On-line: http://web.cs.swarthmore.edu/~richardw/emergence/2006-03-15/N01-1024.pdf

Hope you can make it!| radical incrementalism Name: Date: 2006-03-15 10:56:11 Link to this Comment: 18535 |

But switching gears, I promised Anne I would post this on radical incrementalism:

Okay, now I am really confused!

Evidently folks in business, computing, technology studies, education and even architecture all lay claim to the emergence of radical incrementalism, an idea I feel I first introduced in the early 1990s:

Policy Sciences: Integrating Knowledge and Practice to Advance Human Dignity

And which i have continued to emphasize:

The newer forms of radical incrementalism are mentioned everywhere:

John Seely Brown and John Hagel III,"Flexible IT, better strategy"

Lou Anna Kimsey Simon,"University Outreach: Realizing the Promise through Vision and Accountability"

These are not in my mind equally protean of progressive political possibilities for making emergent more opportunities to live less oppressively.

Other folks extend my version of radical incrementalism in ways that emergence theorists might find more prodcutive:

Joseph Lambert, "Incremental Progress"

Is radical incrementalism an idea worth taking seriously and if so, which verison?

If this is a question that has value for emergence then perhaps you will find these links useful. Otherwise, delete.

| From similarity analysis to evolution Name: Paul Grobstein Date: 2006-03-15 17:27:11 Link to this Comment: 18541 |

A "similarity analysis", of the general kind done by Rich on a language corpus, strikes me as an interestingly "minimal" kind of basis for inquiry/exploration from which lots of other things could follow. By "minimal" what I mean is that it requires VERY few presumptions about what is being inquired into/explored (only that looking for patterns may be productive?) and requires VERY little pre-existing structure (only enough to detect and represent temporal and/or spatial correlations). The latter certainly exists in the unconscious component of the bipartite brain and, arguably, exists in all living organisms/model builders. My guess is that it in fact exists, in at least rudimentary forms (see information and decoders) in the pre-existing "active inanimate", and so needn't be presumed to depend on anything other than on ongoing process of exploration that predates life (ie there is no need to presume a "designer" at any point).

Moving the other direction, similarity analysis readily yields (as Rich showed) "patterns" that in turn challenge one (if one has "story telling capability", which itself may arise without a designer) to try and create "rules", ie "summaries of observations" that are shorter than the catalogue of observations (and so constitute "understanding" the patterns) and have preductive value. An important point at this juncture, as exemplified in the discussion today, is that this step involves (necessarily) an arbitrary choice of which patterns to attend to and of different ways "rules" might be made. To put it differently, no particular set of rules follows inevitably from the similarity analysis. The rules are always a "story", developed (unavoidably) from a particular perspective/reference frame.

What particularly caught my interest though was Rich's notion that one can evaluate the "rules" by rematching them to the patterns, in his case by asking which set of rules is "simplest". This is I think akin to the "fuschia dot" action in the bipartite brain, the bidirectional exchange between unconscious and story teller. And, to make the whole thing even MORE interesting, the choice of "rule set" in turn alters the production of whatever the system is producing (language in Rich's case) which in turn alters the set of observations (Rich's corpus) and in turn a subsequent similiarity analysis and subsequent "rule set". Bingo, evolution, in general and in language.

| and now arising Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-03-15 17:50:59 Link to this Comment: 18542 |

You know, I've been telling Eric Raimy for years that the work he does in linguistics doesn't interest me because "it's just about rules, not about meaning"--but Rich's talk this morning taught me something quite handy about the process whereby meaning arises from rules, which can arise in turn from clusters, which can arise in turn from taking note of similarities, which can arise in turn from summarizing observations, which can arise in turn....

In short, arising out of Rich's work, I can now begin to envision something of a prototype for how inquiry can happen: gathering data, clustering it into patterns, seeing how simple/efficient an account of the governing "rules" one can devise---

and looping on 'round again. Thanks, Rich (and Paul, who really clarified this for me).

This all also seems related to Sandy's further questions about whether thinking "emergently"

can help us to an awareness of how to bring about "incremental change."

Whether that change is "radical"--in either the sense of profound or left-

or socially-justly-leaning, is another matter; this is what I realized in

response to Laura's invitation to us, a while back,

to think about the "failure of feminism" (i.e. women ending up @

home w/ the kids) as an emergent phenomena--since I had come to think of

emergence as a principle that enables change. In the

talk I gave to this group a few weeks ago,

I was interested in going beyond both "normative" and "descriptive,"

to look @ the possibility of intervention...

but what I realized, in the process, was that emergence doesn't

necessarily contribute to positive change

--it's just a useful/skillful/not-so-discouraging way of thinking about

how to bring change about....

Anyhow, am quite curious to see how "knowledge-free" we can be, next week--

and just where that might get us.

Til then, in gratitude,

Anne

| knowledge free Name: Date: 2006-03-18 18:18:53 Link to this Comment: 18587 |

| the logic of traffic jams Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-03-22 16:05:10 Link to this Comment: 18649 |

Not so fast with the dismissal of the knowledge-free. I'm still trying to hold on to my revelation of last week, when I felt I'd been given a prototype for how inquiry can happen: by gathering data, clustering it into patterns, seeing how simple/efficient an account of the governing "rules" one can devise---and looping on 'round again.

So what fascinated me in this morning's session was the attempt of Rich and his compatriots to work from a place of "no logic" to one of logic, to derive semantics out of syntax, rules out of word detection. I found myself wondering how (various) linguists understand-and-express the relation between semantics and syntax; I found myself remembering my own paper about why and how meaning arises, which (among other things) challenges the presumption of a logic underlying morphology, a "sense" that upholds structure (which is what makes puns so disconcerting to linguists....?)

Speaking of which...my first encounter w/ emergence (which led me directly into regular attendance in the emergence group) was a brown-bag talk Panama Geer gave four years ago on decentralization and self-organization. It drew on Mitch Resnick's Turtles, Termites, and Traffic Jams, and it was soon after that I had my first experiential awareness of the logic of emergent systems, in a traffic jam. It amuses me no end that some of our group is now likewise experiencing new-clogged-traffic-pattern emergence as they manfully (sic) try to get to our Wednesday morning discussions. Surely we can use all these hours' worth of discussions to figure out some pragmatic, emergent solution to this dilemma?

| What is NOT emergent (belatedly) Name: Paul Grobstein Date: 2006-03-29 11:04:00 Link to this Comment: 18717 |

What is NOT emergent is to then start looking in the data set for new patterns and new rules in order to make the patterns/rules derived from the data set get progressively closer to the pre-existing set of rules. This is not only not emergent, it is "massaging the data", frequently counterproductive for science/inquiry, and helps to illustrate on the occupational hazards of "normal" science/inquiry. The key point here, as for computer modelling, is that most phenomena can in principle always be accounted for if investigators are given enough degrees of freedom to work with and indeed can usually (always?) be accounted for in multiple different ways. From which it follows that simply coming up with a set of rules that accounts for something is not itself remarkable or necessarily "generative". A common problem of "normal" inquiry, in lots of fields, is that of progressively adding to/fiddling/modifying the story to make it work. After a while (sometimes a painfully long while) people simply lose interest because the research is progressively inward directed (created by the problems of the inquiry itself) and the story gets so complex/talmudic that people can no longer be bothered to keep track of all of it.

This is not intended as an argument against normal science/inquiry. Non-normal science/inquiry too has occupational hazards, both are interdependent, and each ultimately has to answer only to the "generativity" criterion,. But it is interesting (to me at least) that there is a distinctive occupational hazard of normal science/inquiry that relates to giving up its potentially emergent character, to taking as the problem the "explanation" of something "out there" by whatever means we can manage it. Maybe there is a similar issue and warning for non-normal science/inquiry? That one can never actually be "knowledge free" but one can take the degree ot which one surprises oneself as one good criterion for predicating the generativity of what one is doing, whether normal or non-normal?

| more on normal/non-normal inquiry Name: Paul Grobstein Date: 2006-03-29 18:03:19 Link to this Comment: 18720 |

Most interesting, to me at least, was the demonstration that a given piece of research (observatons/interpretations) can (will always?) be seen as either "normal" or "non-normal" depending on the observers (and independent of the intent of the creators). Wheeler certainly has in mind a "story" quite different from the ones many of us use most of the time (starting "without laws" or "space" or "time" and having "a participatory universe" as a central concept, recognizing that the referent for science is not "reality" but "what can be said about the world" with the notion that the observer is always implicated in it). And it was certainly in that spirit that Zeilinger is working ("This possibility of deciding long after registration of the photon whether a wave feature or a particle feature manifests itself is another warning that one should not have any realistic pictures in one's mind when considering a quantum phenomenon ... Zeilinger, 1999; thanks to Sandy for the link).

On the flip side, Zeilinger's work (and earlier/related work by others) can be not only regarded as but reacted to as "normal" science. "Entanglement" was inherent in the equations that gave rise to modern quantum theory and the kind of work talked about today can be seen as simply new sets of observations that have "tested" that theory and are consistent with it. Moreover, one can react to it, as many people (both themselves inclined to normal science/inquiry in their own activities and those not) by puzzling over it in "normal" terms: this is a new observation about "reality"; how come it doesn't fit what I would have predicated given my understanding of "reality"? what (relatively small) changes in my understanding of "reality" do I need to make to fit it in?

An important lesson for me (and perhaps for others?) is that a given set of observations/interpretations does not (ever?) compel people to adopt either a normal or a non-normal science/inquiry posture. It may encourage some movement from one preference to the other but the normal/non-normal distintiction is not inherent in the observations/interpretations taken alone (ie it doesn't reflect an "essential" property of them). Instead, it is an observer dependent distinction. For some people, a given set of observations/interpretations will encourage a major shift in perspective (and hence in how one subsequently asks new questions) while for others it won't, and its only after the votes are in that one can characterize the particular set of observations/interpretations as "normal" or "non-normal". And those votes themselves are, of course, in some significant part bets on "generativity", which itself can also be evaluated only after the fact.

That said, there was still something very exciting to me about the observations/interpretations as Al characterized them. Entanglement is one possible source of this. The phenomenon is certainly intriguing when one first encounters it, but is also at this point pretty familiar to anyone who has been following recent physics developments (as evidenced by, among other things, its having progressed to the practical realms of applied physics). The observations certainly establish that there is some more global connecteness than was imagined in the stories of classical physics, and so might be used by some people to validate their intuitions about global connectednesses in other realms. There are though very significant limitations in directly connecting quantum phenomena to phenomena at other scales, so for the moment any extension to other realms is useful metaphorically at best. For my part, I've never felt that phenomena need to be seen at the level of physics in order to be potentially significant at other levels and so I'm less inclined to be excited about entaglement in these terms. There are plenty of other reasons to suspect that there are larger patterns of connectedness at scales I'm interested in (brains, organisms, societies), independently of whether there are or aren't at the quantum scale. And asking for an explanation of entanglement at the quantum level is missing the point that physics (like any other kind of inquiry) is a "story" (Bohr's "what can be said about the world), and not all story elements have explanations in other terms (the failure of the "action at a distance" explanation). Entanglement, at the quantum level, just IS. For the moment.

What was a little more exciting to me (and led to my simultaneously blasphemous and off-color expression of surprise) had to do with "observer dependence". It was not observer dependence per se that startled me; that too has long been well documented at the quantum level. And that too, just like entanglement, is, for the moment at least, of no more than not necessary metaphorical interest for other levels of inquiry (where observer dependence can clearly be demonstrated directly). What surprised and interested me was the inquiry into the NATURE of "observer dependence", the observation that one doesn't actually have to make an observation so much as to simply set up the circumstances by which an observation might be made. THAT, I think, is actually telling us something new, certainly at the quantum level, probably be metaphorical extension to other levels, and possibly even directly. Given the (apparent) history of the universe prior to the appearance of humans, it has never made sense to me that the collapse of the quantum wave function (to yield actuality rather than probablistic potentiality) depends literally on a "human observer" and can only occur in the presence of one (see information working group discussion). My guess is that the Zeilinger work and further work like it will help to clarify what is actually meant by "observer dependence", and that it will turn out not to require human beings or any other comparable agent (ie a story teller).

What was though MOST exciting was the more general story telling context, the notion of a world continually evolving out of the actions of many observer/participants (some of them themselves story tellers). This I contend is indeed "non-normal" science/inquiry, as evidenced not only by the wide spread efforts to make it more "normal" ("how does it change is my question" ... maybe it doesn't?) but also by the opening of new questions that might not otherwise have been asked (what IS an "observer"?). That one might get to this particular vantage point either as a physicist or as a neurobiologist further suggests that this particular odd platform might in fact by sturdy enough to support ongoing, perhaps even generative inquiry. And, who knows, perhaps inquiry of a kind in which physical observations and neurobiological ones can be reciprocally fundamental. Maybe of a kind in which observations of social scientists and humanists could be as well? If enough of all of them (and everyone else too) could get their heads fully around the idea that all inquiry is necessarily and inevitably "story", and that there is nothing to be lost and lots to be gained by recognizing that one is always and necessarily personally involved with and a contributor to the stories one tells and their continuing evolution?

| Emergence and Quantum Theory Name: Date: 2006-03-30 11:11:56 Link to this Comment: 18741 |

| Getting Farther away--I think this is the right di Name: Sandy Schr Date: 2006-03-30 16:32:39 Link to this Comment: 18749 |

| coming at this from another direction Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-03-30 22:29:03 Link to this Comment: 18754 |

I spent many hours this week sitting in on a court case, arguing with the chicken processing plant that abuts my farm in Virginia about who "really" owns a small bit of property we both lay claim to. What I learned (aside from the saying that "you never want to be a plaintiff in a boundary dispute") is that

I was well prepped for Al's presentation Wednesday morning, quite softened up and ready to be shown the degree of genuine indeterminacy in physical (as well as in all cultural) systems. And/but I'm puzzled/intrigued by Sandy's subsequent dogged pursuit of the details about how things operate on the quantum level.

As I observed in the car, driving back from that uncertain place (Swarthmore) to the place of certainty (Bryn Mawr), I'm not convinced that understanding the story of how wierdly things work @ the quantum level necessarily gives us any guidelines for understanding how they (do, or should) operate on a social or cultural or political level. This follows Paul's observation, above, that "asking for an for an explanation ...at the quantum level is missing the point that physics (like any other kind of inquiry) is a 'story'"

--i.e., no more "foundational," no more "real" than any other account, at any other level.

| Michel Serres Name: Date: 2006-03-31 17:37:40 Link to this Comment: 18776 |

| Towards dissolving boundary disputes ... Name: Paul Grobstein Date: 2006-04-01 09:15:26 Link to this Comment: 18778 |

| some more resources Name: Paul Grobstein Date: 2006-04-05 10:42:25 Link to this Comment: 18841 |

Name: Sandy Schr Date: 2006-04-05 11:09:49 Link to this Comment: 18842 |

First, it seems that analytical philosophy starts with assumptions of methodological individualism, ala rational choice theory in economics (as represented by Kenneth Arrow's Impossibility Theorem) and only then takes the long way around to getting to social holism that assumes groups are real and have a status of their own where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Many people in the social sciences, especially since Marx and most especially since Durkheim, start with social holism, where classes, or social groupings have a real status independent of the individuals who comprise them.

Second, the analytical approach is to start with a Cartesian set of assumptions where the autonomous individual and her or his consciousness is assumed to be literal and then the issue is to see to what extent a group consciousness, mental state, in the form of knowing or believing, is analogous. This then becomes various forms of "socially extended cognition." Yet many practitioners of social wholism question whether we should start with autonomous individual consciousness as the touchstone of what is to be taken to be literal and judge everything else as various extensions of that. What is all consciousness is from the very beginning social.

For instance, John Dewey, relying heavily on George Herbert Mead, believed that intelligence was by definition social and individuals partook of that shared social capital, they could in that sense "bank" on it. Cognition in this sense is always already social even before it is extended to the group. The distinction between individual and group consciousness deconstructs itself on when we see how what Jacques Derrida calls, questioning Edmund Husserl, a certain culturally encoded "western metaphysics of presence" or "logocentrism" is operating in the thought experiments regarding whether groups think like individuals. The entire process is reversible.

Even though John Searle was at pains to insist on the mind/brain distinction in the Chinese box experiment, he and Jacques Derrida disagreed about how to understand things like consciousness and its relationship to language. Their debate is especially relevant for thinking about what should be taken as literal versus what is to be seen as figurative or metaphorical. In spite of this (or because of this--I am not sure), Searle has his own way of suggesting that the mind is emergent from the brain. Here are some relevant links, provided in hypertext formatting, now that I have been properly and graciously educated by Anne:

"Reality Principles: An Interview with John R. Searle"

Limited Inc, by Jacques Derrida

"Searle vs. Derrida: An Artificially Translated Version"

The last link is a bit of whimsical verisimilitude. This is from a webpage in French that is translated by the computer. It is a horrible translation, perhaps not definitive evidence but suggestive that artificial intelligence is a pale, artificial version of human intelligence and needing much more programming before it can operate at a higher level of consciousness where it can recognize and practice its own intentionality. The computer knows some rules for translation but it has a really rough time connecting the dots and imputing meaning to the words it translates. As a result, a lot gets lost in the translation. What that lot is is perhaps the difference between the brain and the mind, between conscious intelligence and artificial intelligence.

As for applications, public opinion research in recent years has moved heavily into the idea that "the public" is manufactured by polls rather than reflected by them. And once constituted, "the public," as a reified entity operates in our politics as a constraint on individual consciousness, belief an opinion, such that, for instance, people who are polled about what they individually think is the most important social issue say what they have heard (usually from the mass media) is "the public's" major concern. So many people will rank crime high even though they do not think themselves that crime is a major social issue. Here the group, in the form of "the public," influences what the individual thinks or believes. Individual opinion is constructed out of what is taken to be group opinion, raising the issue of the extent to which people have autonomous individual opinions in the first place.

Additional research shows that changing the information about what "the public" believes influences what people say they believe. Further work on narrative frames adds to this hypothesis.

| Daniel Dennett Name: Date: 2006-04-05 12:53:28 Link to this Comment: 18844 |

Here's two great links on Daniel Dennett and his functionalist account of mind to brain, belief to knowing, freedom to determimism, and evolution to athesism. I think there is a version of emergence in here somewhere:

"Interview with Daniel Dennett

"Stage Effects in the Cartesian Theater:A review of Daniel Dennett's Consciousness Explained"

| one story Name: Anne Dalke Date: 2006-04-07 00:01:49 Link to this Comment: 18888 |