|

|

Home

| Calendar | About

| Getting Involved

| Groups | Initiatives | Bryn Mawr Home | Serendip Home | ||||||||||||||||||||||

The TriCo Language Seminar Series |

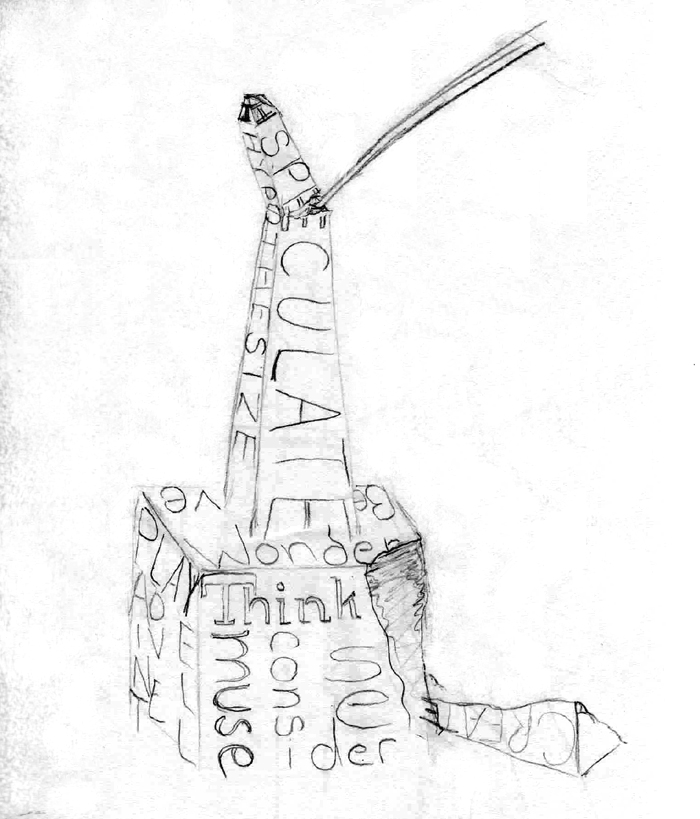

"Words," by Sharon Burgmayer, in relation to the Writing Descartes forum |

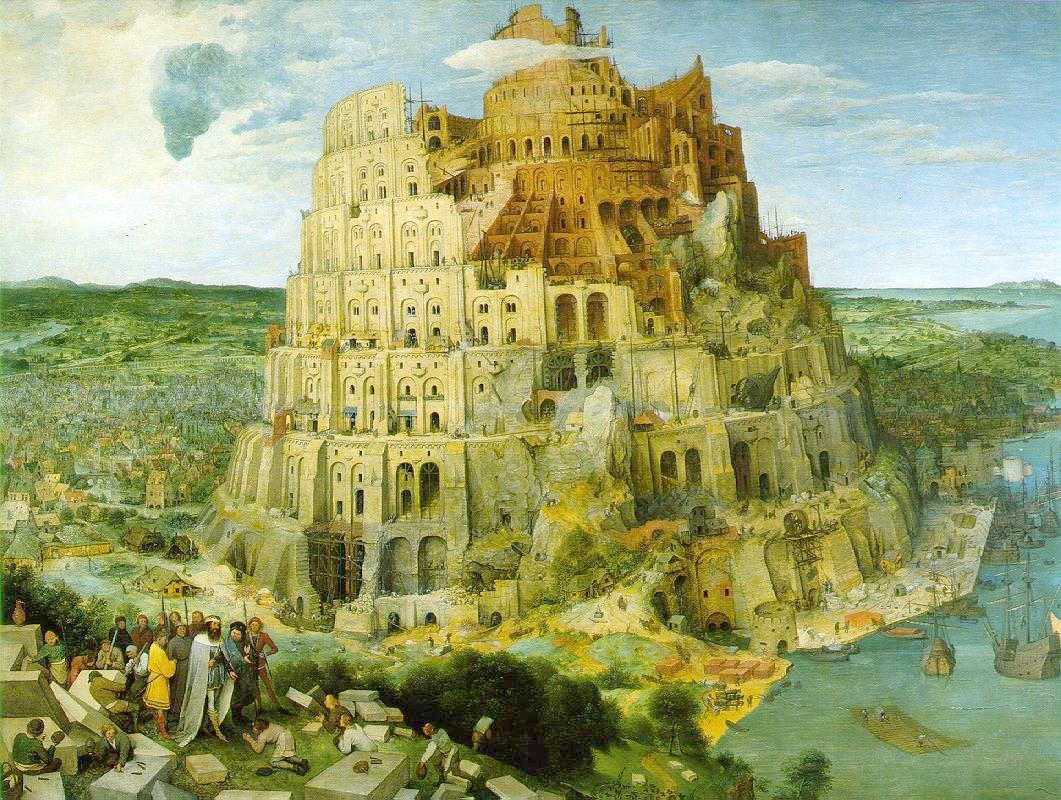

by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, as represented @ Amersterdam-Holland-Travel.com |

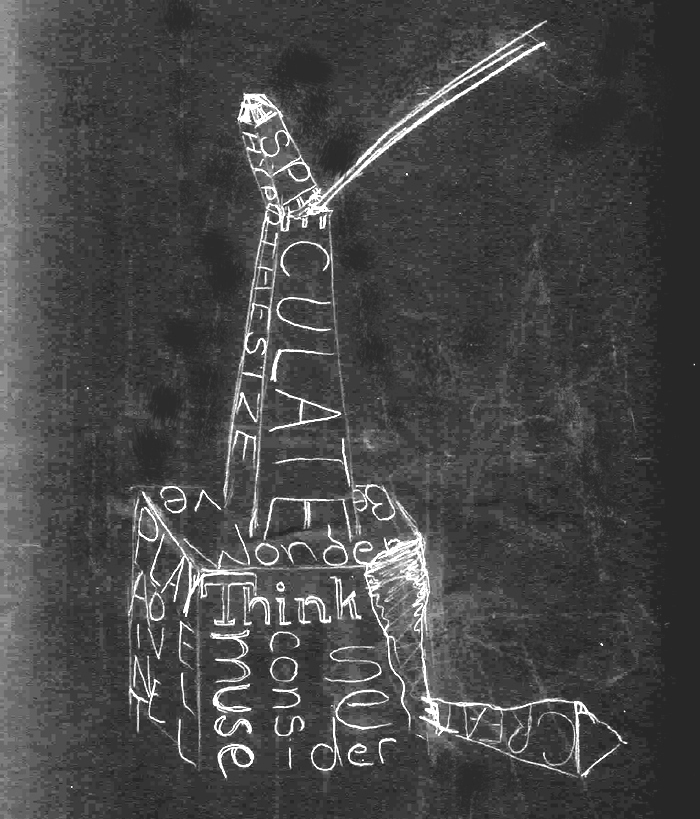

"Words Invert" by Sharon Burgmayer |

| The Tower of Babel Story (from Genesis 11:1-9) And the whole earth was of one language, and of one speech. And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there. And they said one to another, Go to, let us make brick, and burn them thoroughly. And they had brick for stone, and slime had they for mortar. And they said, Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth. And the LORD came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of men builded. And the LORD said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do. Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech. So the LORD scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the city. Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the LORD did there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the LORD scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth. Without one language: the people are powerless to act... | A Contemporary Counter-Story, from The Two Cultures: A Conversation (2001) : In a class session devoted to analysis of some poems...the conversation turned to the question of differences between "languages". If indeed there were highly unambiguous "languages" (mathematics, as well as, for example, computer programming languages), how come ordinary "language" was invariably highly "ambiguous" in interpretation (so much so that poetry was a legitimate art form and "literary criticism" a legitimate profession, with a method not dissimilar from "science")? What emerged from the discussion was the idea that ordinary language is not "supposed" to be unambiguous, because its primary function is not in fact to transmit from sender to receiver a particular, fully defined "story". Ordinary language is instead "designed" (by biological and cultural evolution) to perform a more sophisticated, bidirectional communication function. A story is told by the sender not to simply transmit the story but also, and equally importantly, to elicit information from/about the receiver, to find out what is otherwise unknowable by the sender: what ideas/thoughts/perspectives the receiver has about the general subject of the story. An unambiguous transmission/story calls for nothing from the receiver other than what the transmitter already knows; an ambiguous transmission/story links teller/transmitter and audience/receiver in a conversation (and, ideally, in a dialectic from which new things emerge). Without one language: the people have a means of discovering things they didn't know.... |

In other words, it is the restraint itself which is productive of meaning.

We might call this...

Driving a Car with Breaks, or

Test Driving Where Stories Come From

...and position it between

| "Every car without breaks is dangerous"-- "Some Remarks on Universal Quantification with Natural Language in Mind" (Shizhe Huang @ BMC 10/21/04) | and | "A Story about Parked Cars: The Intersection of Neurobiology, Linguistics and Sociology"(Eric Raimy, upcoming @ HC 12/2/04) |

Thinking about why don't linguists and literary folk don't talk with one another...

wanting to try out some ways of talking together....

I. The story begins with Shizhe's highly theoretical and formal search to

"secure a variable in the scope of a universal quantifier..."

This was an inquiry into the nature of quantification:

what does it mean to say that "everything is x"?

To get at the meaning of that linguistic pattern,

Shizhe reviewed a formalism ("skolem function") in which value x determines value y;

we moved from a discussion of empty sets (if x is empty, there is no pairing, so y has no value?),

to an understanding that not 2 but actually 3 things (=sets) are involved in the act of universal quantification.

That (hidden) third element, or "variable," could be an indefinite adjective (which gives the a larger range)

or tense (which anchors the sentence onto a point in a time line).

To get there, Shizhe led us through a range of examples, asking if they "sounded" or "felt" right to us:

| "Every car without breaks killed a squirrel." "Every car without breaks ran over a child." "Every car without breaks is dangerous." |

|

And my mind leapt over the questions about HOW sentences made meaning to WHAT the meaning was...

What IS a null set?

Isn't it (or couldn't it be?) defined (evacuated? filled?) by context?

How can the subject class be empty, and the sentence still be true?

What was the context of this conversation?

Why were all the sentences violent ones?

What "didn't sound right" to me was not HOW, but WHAT the sentences were saying....

II. That is the space where I want to go tonight:

that gap between linguistic and literary meaning-making,

the place between semantics and (the interpretation of) literature,

between the search for a logic that gives us meaning, and the sorts of searches (we do in English House?)

which seem to step off from logic, form, and the rules of symbol manipulation to...

evoke what is not yet known, what surprises.

a search for the predictable in order to flush out (and produce?) the unpredictable.

Rob Wozniak, BMC Psychology |  Tri-Co Linguistics |  Paul Grobstein, BMC Biology |

...each of them contributing to, none of them responsible for, what I have to say...

The backstory to all of this, its framing concept, comes from contemporary work in emergence (complex systems). The argument arises from two years' discussion, in the Emergent Systems Working Group, of the world as a complex interactive system that is unpredictable and indeterminant (both forwards and backwards). As summarized by Paul,

Emergence = a perspective and story-telling genre that is distinctively characterized by efforts to make sense of observations on the presumption that there is no architect, planner, or intentional "first mover" (one anticipating future outcomes) nor need there be any conductor. There is only an originally and still largely undirected play of entities which become parts of larger entities which become parts of still larger entities and so on. Over a long period of time, the process has, in a quite recent development, created entities that wonder and ask questions about the process itself and, in doing so, are able to find ways to influence and mimick that process.

Or, as Darwin said. "Give me Order, and Time, and I will give you Design"(Daniel Dennett, Darwin's Dangerous Idea, p. 64).

|

|

|

Emergence creates a problem for the nature of knowing: Because effects are emergent, prediction is not reliable. And because effects are emergent, deduction is insecure. We can't predictably go forward (because of the complexity of the interactions), and we can't reliably go back (because the loss of information in arriving at "meaning" is not fully recuperable). The unpredictability of the future and the irreducibility/irreversibility of the present (the inability to reduce an effect to its causes, to play the tape predictably backwards) arise from the same cause, for the same reason. Not being predictably predictive and not being reliably deductable are the result of the emergent nature of the universe. And (punch line)

Irreversibility creates (i.e. induces us to produce) stories;

indeterminacy prods us to make up stories about

how we got from what was to what is, from what is to what will be.

Storymaking (which constitutes the production of meaning)

is how we negotiate the gap between what was and what is,

between what is and what will be.

It's how we explain the passage; we can't help but do it.

This rubric calls attention to the unpredictability of the process and its outcome. There are rules for language use, but literary language plays with and continually revises them. In "The Origin of Language," Michel Serres speaks quite strikingly about successive levels of interpretation, in which each level functions as a "rectifier" or "filter" integrating what is "noise" on the level below into "information" on the next one up. "Noise" may be defined as the source for what is new, the place where meaning we haven't yet recognized may arise, if we know how to attend. And literature is the place where this "rectification" occurs....

(From Paul again:)

- the potential at any give time is greater than what is realized at that time

- evolution is irreversible: one can neither perfectly predict the future nor perfectly recover the past

- an utterance (signal) is a particular realization of a larger potential, an irreversible compression (neither fully predictable nor fully explainable) and meaningless without a receiver

Some examples--

Last month, Rob made a presentation in the Emergence Group about The History of 'Emergence' in the History of Psychology," which included The Clarifying Example from Mars, or That Vs. What Is

Knowledge of the Electrochemical state of Every Cell in Your Brain at the Moment You Perceive A Cup Will Record that you Perceive a Cup, but not WHAT the Perception of the Cup is Like to You (or: mental states may be extensionally but not intensionally equivalent to states of the nervous system: mental terms cannot be replaced with neural terms without loss of meaning; there is surplus meaning in mental terms, mental terms cannot be replaced with neural terms without loss of meaning).

The plugged-in Martian, who knows the states (=the rules) but not the experience on (another's) inside,

is for me a figure for the literary critic listening to the linguist:

I can hear, even understand, the descriptions of all the rule sets,

but they give me no sense of meaning in the way that means anything to me....

Rules for "universal quantification" don't tell me (for instance) what I want to know:

why we write violent sentences (=why we have violent thoughts).

Rob's description of "surplus meaning" (neural states being extensionally but not intensively equivalent to perception: to "see" a cup "means" more than what an account of the state of the neural networks describes) is an account, in my terms/ landscape, of the process of literary interpretation, in which any "text" always exceeds the grasp of any "interpretation," any "reduction," any story of what it is/does. This is pure Derrida: the original is always deferred - never to be grasped.

If Rob is "right" in describing the way in which emergence creates a problem for "knowing," because deduction is insecure, prediction is not reliable--that is, because the future is unpredictable and the present is not reduceable to the past (not just time, but the information transferred is irreversible)--THEN MEANING IS THE WAY WE TRY TO BRIDGE THE GAP. Meaning is thus in no sense "surplus"; it's the explanation, the story we "make up" to explain how we got from A to B, how we might have gotten to B from A.

Rob's answer to the question of where the Iliad resides--in the interaction between the sequence of words and the decoder/reader--is the central idea of a long-important methodology in literary studies known as reader-response theory, which fits quite nicely into the notion of meaning-as-relation: textual meaning is constructed in the interaction between the writing and the reading; it comes into existence when the text is read--and is persistently revised as readers compare and collate their readings with one another, searching for patterns common among them, recognizing when the patterns break down, where new stories are needed.

This process can effectively be exacerbated in teaching.

For instance, in the first-semester College Seminar Paul and I teach on Telling and Re-telling Stories

the first sequence of assignments is an insistent re-telling of fairy tales:

Draft A: Compose your own life of learning.

Draft B: Re-compose your life of learning as a fairy tale (turn the concrete specificity of your life experience into an archetypal tale).

Draft C: Using Bettelheim's methodology (or another), analyze your fairy tale (step back and do a critical reading of your archetypal story).

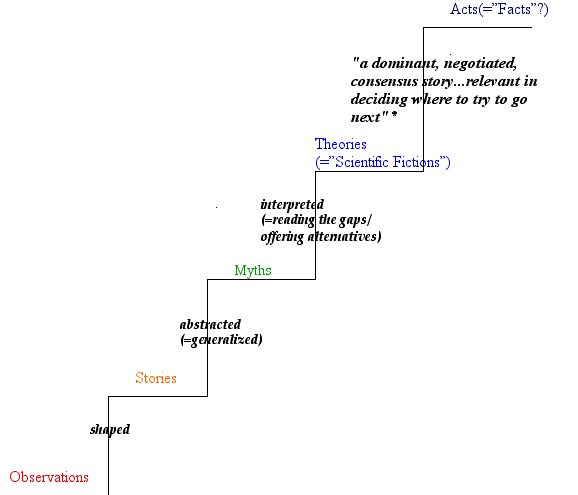

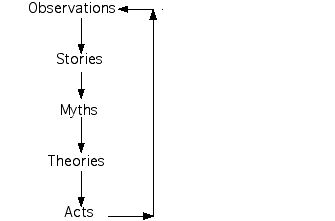

This (disciplined version of a natural) sequence of evolving stories--ever-more abstract, ever-more theoretical, ever-more consensual (and therefore ever-more assailable and questionable) can be figured thusly:

*figure reflects a conversation between Paul and me, and is my reformulation of ** phrase is taken from an interchange between Paul and Paula Viterbo on the Brown Bag Forum

his attempt to make sense of science in terms of elaboration of "stories," rather than accumulation of "facts"

|

|

My claim is that the use-value of literature (and language more generally) emerges in these "steps," the transitional moments or interstital places where (the old) rules don't apply, where there is an alteration in meaning, where negotiation and interpretation are necessary--and where (therefore) newness arises. We see this in the evolution of New Literary Forms. New Literary Interpretations. New Words. Re-making the Meaning of Old Ones.

Some Perfect Ones:

What do you get when you drop a piano down a mine shaft?

What do you get when you drop a piano onto a military base?

Why couldn't the pony talk?

What did the string say when the barman refused to serve him

(and he returned, a second time, all frazzled and frayed)?

Why-and-how do those puns work?

What is the logic of their working?

She reasoned, "To err is human, to forgive, bovine."

A man wanted to buy his wife some anemones, her favorite flower.

Unfortunately, all the florist had left were a few stems of the feathery ferns he used for decoration.

The husband presented these rather shamefacedly to his wife.

"Never mind, darling," she said, "with fronds like these, who needs anemones?"

Compare: some etymologies--

in Latin... "cultura" refers to "tilling or cultivating the land," and by extension, through the fifth century C.E., to the application of cultivation: to our minds, our faculties, our acquaintances, even to "cultivating" a memorial (by picking the lichen out of it!?). Closely related to the Latin term "cultus" (worship, as of a God), "cultura" is, paradoxically, an insistently agricultural metaphor, since "culture" is today thought to be "what farmers don't have time for," a higher, "more worthy" work than manual labor of any sort.

"Culture," "cultus" and "colonize" are derived from "colo," which means "to live in." Etymologically, we "live in" ("colo") a place, "cultivate" it for extended use, establish "cultura" there; with increased leisure and money we adorn ourselves and our wives [sic] and develop generic "cultural" practices such as worship ("cultus"). In its origins, the word "culture" has a huge semantic range, out of which, in our present use of the term, we select a very small set. For instance, when we speak (as we have been speaking here for the past eight months) of the "culture of science," we are referencing what thinkers do, not the unconscious work of laborers.

Footnote on how a fact becomes an act:

a recuperation of "fact" from the O.E.D., where (in the first four instances) it means "act" (from L. fact-um, thing done; was adopted as "feat"). It's fact as act that I want to highlight, fact as action which most interests me: fact as praxis, pusher, mover, provocateur....

a fact, I'll go so far as to provocatively claim, is that which has the power to cause action. It's not just any one of an infinite number of stories, but only the story with the punch (perhaps it's the punch that fiction lacks?)

How and why....?

Jonathan Culler, On Puns: The Foundation of Letters (1987, pp. 1-16):

...the interest of etymologies lies in the surprising coupling of different meanings.... Etymologies...give us respectable puns, endowing pun-like effects with the authority of science....Etymologies show us what puns might be if taken seriously: illustrations of the inherent instability of language and the power of uncodified linguistic relations to produce meaning....etymologies, like puns,...are instances of speakers intervening in language, articulating relations....intently or playfully working to reveal the structures of language, motivating linguistic signs, allowing signifiers to affect meaning by generating new connections....

Not surprisingly, in both the realm of puns--relations between signs in a language at a particular moment--and the realm of etymology--relations between signs from different periods--there is no dearth of people anxious to control relations, to enforce a distinction between real and false connections....the exploration of formal resemblance to establish connections of meaning seems the basic activity of literature; but this foundation...depends on relations...is a function of practices of reading, forms of attention, and social convention....

Punning frequently seems...a structural, connecting device...to offer the mind a sense and an experience of an order that it does not master or comprehend....we are urged to conceive an order.....Insofar as this is the goal or achievement of art, the pun seems an exemplary agent....

The literary critic calls this shaping of order out of disorder "exemplary."

The linguists seem to find the process more troubling....

(Thanks to Eric Raimy, Linguistics 003: Language Play)

puns make it clear that the boundaries involved [whether competence-performance, knowledge of language or knowledge of the world] are both highly mutable and indefinite ....perhaps we need to revise our statements about...those aspects of language that we have predicated on them....paranomasia gives us evidence both of speakers' awareness of the systems of language and for their understanding of how these systems interconnect. Linnea Lagerquist, "Linguistic Evidence From Paronomasia." Papers from the Sixteenth Regional Meeting, Chicago Linguistic Society (April 17-18, 1980). Ed. Jody Kreiman and Almerindo Ojeda. 185-191.

In a perfect pun, a single phonological entity is to be understood as representing two distinct lexical items. In an imperfect pun, one phonological entity stands for a phonologically distinct but similar entity, the two representing two distinct lexical items....divergences might be argued to follow from differences between perception and production. But much remains unexplained.... Arnold Zwicky and Elizabeth Zwicky, "Imperfect Puns, Markedness, and Phonological Similarity: With Fronds Like These, Who Needs Anemones?" Folia Linguistica 20, 3-4 (1986): 493-503.

pun's perfidious status as an aberrant element within the linguistic structure....Puns play with meaning....they give the wrong names to the wrong things--and they disturb the proper flow of communication....in confusing sense and sound...normal rules governing etymology and lexicography are temporarily suspended while speculation and fancy roam free.... puns...subvert the one-to-one relation between signifier and signified...fracture the sign....the word can mean two or more things. It is because it ambiguates meaning that the pun disturbs the system of communication by which meaning is conveyed....the interpretative process...ultimately restores priority to the serious business of making sense, to showing what a pun finally means....a freak coincidence...becomes a causal and motivated connection...is presented as lexically appropriate...Once limited to a certain point, the pun becomes masterable and pleasurable. Catherine Bates. "The Point of Puns." Modern Philology 96, 14 (May 1999): 421f.

Meaning-making arises, then, from the interaction of

- a set of rules, a history of their relations and

- the creative (and somewhat random) action of generating, then editing and elaborating connections between words, texts and one's own experiences.

- the inevitability of pattern-making with

- the desire of an individual to hand over the ability to control in order to BE surprised (and to surprise others in turn) by what arises.

Both keynotes are sounded by Margaret Drabble, The Radiant Way (1987):

Esther's mind moved quickly, apparently at random; she had a habit of introducing subjects and growing bored, within minutes, of the interchanges she had herself provoked....she was reading and annotating by her own interleaved systems, a system which had evolved from her inability to concentrate fully on any one topic for more than ten minutes. It had thrown up some very challenging cross-references in its time....Esther...made a note...and read on, waiting for some little current to leap from one open page to the other, from one lobe of the brain to the other, and to ignite a new twig of meaning, to fill a small new cell of the storehouse of her erudition. She was content with twigs and cells, or so it seemed. Sometimes, when accused of eccentricity or indeed perversity of vision, she would claim that all knowledge must always be omnipresent in all things, and that one could startle oneself into seeing the whole by tweaking unexpectedly at a surprised corner of the great mantle. (22, 78-79)

Esther is the random-generator of connections and in her friend Liz (just before her party begins) is driven contra-wise by the desire NOT to know, to be surprised:

As she sat there, she experienced a sense of what seemed to be preternatural power. She had summoned these people up, these ghosts would materialize, even now they were converging upon her in their finery at her bidding, each of them wiling to surrender a separate self for an evening....The dance would be to her tune....It would be a large assembly....Surely this night the unexpected would happen, surely she had summoned up the unexpected. She had, of late, felt herself uncannily able to predict the next word, the next move...had felt in danger (why danger?) of too much knowledge, of a kind of powerlessness and sadness that is born of knowledge. For these reasons, perhaps, was it that she had decided to multiply the possibilities so recklessly, to construct a situation beyond her own grasping? A situation of which not even she could guess the outcome? Had she wished to test her powers, or, a little, to lose control and stand aside? To be defeated, honourably, by the multiplicity of the unpredictable, instead of living with the power of her knowingness? With the limits of the known?....(8-9)

The way in which this process operates, in the making of literary forms,

was well explained by Dorothea Leichert, Beauty and Economics:

I have a suspicion that aesthetic pleasure is a biological phenomenon which rewards us for remaining in situation with economic possibilities, with the right kind of mix between organization and disorder. These ideas were triggered when I heard that movements in ballet came from fencing movements (a similar parallel holds for dressage). The parallel would be that in either pattern you want to avoid movements that could throw you off balance and would be hard to correct. From my own experience drawing I also know that initially I seem to be concerned in striking some kind of dynamic "balance" on the page....I would hypothesize that most systems who are undergoing healthy changes show certain patterns of variability which are in a mid-range between order and disorder, and that we may have developed our aesthetic sense as a reward system to learn to be attracted by them and avoid others with characteristics of catastrophic change....the dialectic between order and change would also be a powerful motivator for learning: we integrate data into a pattern, then start to get bored by it as we get used to it and take the next step of looking for a new pattern, but still influenced by the context of our previous experience.

A similar process works in the evolution of new genres and new fields of study,

as explained by Michael Tratner (11/03 e-mail):

the outlier, in literary history, that matters is the one that somehow generates a whole series of object similar to itself....a text that stands as simply 'different' from all the others around it (in a period, in a genre...) is not very important unless it somehow provides a pattern for repeated variants....for a surprising text to be readable to many different minds, it must have some regularity, and for it to generate the desire to be read by many persons, it has to provide something 'unusual' that is at the same time repeatable...for a text to be both surprising and regular/original and influential it has to interact not only with the norms for texts, but with the questions being debated about texts at that moment: the surprise that is also regular or predictive....

Meaning arises from unpredictable and social (=increasingly unpredictable BECAUSE social) creative process. Literary analysis is the making of new stories out of the stories we have preserved; the most useful of those are continuously generative of what is new. The WAY such new stories get generated is an emergent process: it involves alteration between contraction and expansion ("an outlier provides a pattern for repeated variants") as interactions in the environment leave traces (in literature) which are continuously picked up (in literature and literary theory) and re-combined in new configurations.

Some examples:

Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness (1899)

Chinua Achebe, "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness," Hopes and Impediments: Selected Essays 1965-1987.

Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart (1958)

Francis Ford Coppola, Apocalypse Now (1979)

Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre (1847),

mediated through Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak's "Three Women's Texts and a Critique of Imperialism" (1988)

explains the generation of Jean Rhys's Wide Sargasso Sea (1966)

From The Story of Evolution/The Evolution of Stories: Moby-Dick gets re-told through the eyes of a 19th century feminist, as imagined by a 20th c. feminist: Michel Foucault, intro. Herculine Barbin: Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth-Century French Hermaphrodite (1838; rpt. 1980)

The same process occurs in the production of literary criticism:

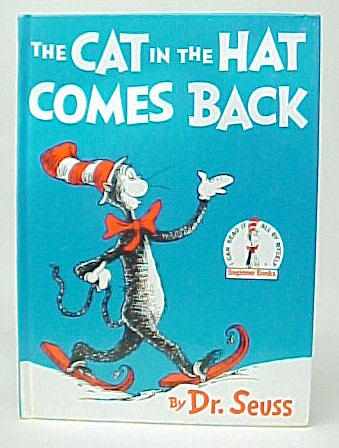

William Spaulding, director of the education division at Houghton Mifflin...asked Geisel to write a story that used only a limited number of similar words, words recognizable by a first grader....The success of "The Cat in the Hat" persuaded [Random House's publisher, Bennett] Cerf to start a division...called Beginner Books....

The cat's improvisations with the objets trouves in the home he has invaded are obviously an allegory for his creator's performance with the two hundred and twenty arbitrary words he has been assigned by his publisher. The cat is a bricoleur. He has no system--or, rather, his system is to have no system. He is compelled to make meaning from whatever is there. He fails, the bricolage topples, the fish ends up in a teapot; and this hint of semantic instability is expanded on in Dr. Seuss's most difficult work (No. 26 all-time), "The Cat in the Hat Comes Back," published in 1958.

"The Cat in the Hat Comes Back" is the "Grammatology" of Dr. Seuss. It is a book about language and structure, those Cold War obsessions.... These semiotic felines do exactly what a deconstructionist would predict: rather than containing the stain, they disseminate it. Everything turns pink. The chain of signification is interminable and, being interminable, indeterminate. The semantic hygiene fetishized by the children is rudely violated; the "system" they imagined is revealed to have no inside and no outside. It is revealed to be, in fact, just another bricolage. The only way to end the spreading stain of semiosis is to unleash what, since it cannot be named, must be termed "that which is not a sign." This is the Voom, the final agent in the cat's arsenal. The Voom eradicates the pink queerness of a textuality without boundaries; whiteness is back, though it is now the purity of absence--one wants to say (and, at this point, why not?) of abstinence. The association with nuclear holocaust and its sterilizing fallout, wiping the planet clean of pinkness and pinkos, is impossible to ignore. It is a strange story for teaching people how to read.

Here's how Culler (in Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction ) describes what Menand did:

"Failure" itself doesn't "fail"; it is productive of meaning.

Alternatively; might this story help us make sense of the current project of re-naming the Feminist and Gender Studies Program "Gender and Sexuality," in our own role in the continuing evolution of what these words mean? (For example: might the emergence of a new "meaning" for feminist "mean" that we don't use the word in the title of the program any more??)

(The Bible, Shakespeare...)

Herman Melville. Moby-Dick (1850):

He's a grand, ungodly, god-like man, Captain Ahab.... I felt impatient at what seemed like mystery in him, so imperfectly as he was known to me then...."my boy, he has a wife--not three voyages wedded,--a sweet, resigned girl. Think of that; by that sweet girl that old man has a child" (78-79)

"Captain Ahab was neither my first husband nor my last...." (1)

Sena Jeter Naslund. Ahab's Wife; or, The Star-Gazer (2000)

Jeffrey Eugenides, Middlesex (2002)

"A Very Short Introduction to Literary Theory," aka Reading The Cat in the Hat Comes Back

Cf. Louis Menand, "Cat People: What Dr. Seuss Really Taught Us." The New Yorker. (December 23 & 30, 2003):

"Meaning is context-bound....context is boundless; there is no determining in advance what might count as relevant (67) ....

[theory] is endless...an unbounded corpus of writing which is always being augmented...

a resource for constant upstagings....unmasterable...open ended...

the condition of life itself...the questioning of presumed results and the assumptions on which they are based.

The nature of theory is to undo...what you thought you knew, so the effects of theory are not predictable (15-17, my emphasis).

(and the interpretations of its meanings, the results of the encounter

between text and reader, code and de-coder which we call literary theory)

generate new accounts, new stories, in order to traverse the gaps between

what is and what was, what is and what may be.

It is in the absence of clear cause and effect that stories arise

to explain the distance between past, present and future

(it may even be the stories which CREATE the sense of past, present and future).

It's precisely the failure of any story ever to tell the whole story, to reliably fill in all the gaps,

which makes them endlessly productive of new ones.

For instance:

Place of the US in the World Community - Nov 04 Forum:

Efforts to tell a social/common story about the election observations...

the complex resultant of all of the individual stories we each choose to tell?

How much of the future is determined by the past?

Please join in....

![]()

![]()

![]()

Alternatively: does this account of meaning-making leave (for instance)

any place for the linguists to stand, to link from?

What gaps remain in between you and me/us and them?

Can we write a story together/build a bridge to drive across them?

Back to Tri-Co Language Seminar Series

Home

| Calendar | About

| Getting Involved

| Groups | Initiatives | Bryn Mawr Home | Serendip Home

Director: Liz McCormack -

emccorma@brynmawr.edu

| Faculty Steering Committee

| Secretary: Lisa Kolonay

© 1994-

, by Center for Science in Society, Bryn Mawr College and Serendip

Last Modified:

Wednesday, 02-May-2018 10:51:18 CDT