Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

|

Psychoanalysis and Neuroscience Forum

|

|

Comments are posted in the order in which they are received,

with earlier postings appearing first below on this page.

To see the latest postings, click on "Go to last comment" below.

Go to last comment

Greetings ...

Name: Serendip

Date: 2003-08-24 15:07:55

Link to this Comment: 6289 |

Welcome to the forum area for discussion of

Psychoanalysis and Neuroscience: Enemies, Acquaintances, Bedfellows?. Like other forum areas on

Serendip, this is a place for public informal conversation. Read what other people have to say, and leave your own thoughts and reactions for others. The idea is that thoughts in progress are important: everyone can learn from what other people are thinking and have their own thoughts changed by reading the thoughts of others. So relax, enjoy, and let's see what sense we can make of the relation between psychoanalysis and neuroscience, and what contributions we can make to others thinking about this and related matters.

introduction-PG

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2003-09-28 20:33:03

Link to this Comment: 6653 |

Greetings. I'm glad to be here, and looking forward to an engaging and important conversation, both here and on

Wednesday evening, 8 October, and hopefully continuing after that.

I'm a neurobiologist rather than a psychoanalyst, psychiatrist, therapist, or social worker. But I'm also a parent, an educator, and a human being concerned for all these reasons (and personal ones as well) about the current state of mental health care in our culture (and elsewhere).

My sense is that, for very pragmatic reasons, there is a compelling need for the various professional communities with interests in mental health to make common cause, to recognize both their commonalities and the usefully different perspectives and methodologies they have to contribute to a shared enterprise. I hope this conversation will contribute to steps in that direction.

Of course, I also think our conversations will address fascinating and quite significant intellectual questions needing to be clarified in ways that yield both new understandings and new lines of productive exploration. For both reasons, I'm very much looking forward to the sharing of ideas both here and in person.

Introduction--EF

Name: Elio Fratt

Date: 2003-10-01 07:09:50

Link to this Comment: 6741 |

I'm a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst and I'm pleased to be on this exciting panel with my friends Paul Grobstein, Syd Pulver, and Susan Levine. But I don't think we're going to be able to get an interesting discussion going here just by being friendly. We need a little controversy. So let me start by registering a concern:

If neuroscientists generally treat the meaning of psychoanalysis the way Paul treated the meaning of Emily Dickinson's poem in the paper he posted for this conference, then psychoanalysis is in big trouble!

THE BRAIN is wider than the sky,

For, put them side by side,

The one the other will include

With ease, and you beside.

Paul thinks Emily means that the self is really in the brain, explainable as a function of the brain, or, as Paul put it, that "the brain might indeed prove to be the repository of all aspects of human behavior and experience, up to and including the self." And I learned by doing a simple google search that quite a few neuroscientists including Nobel-Prize winner Gerald Edelman agree with Paul and like to cite this stanza on behalf of their own belief system. But they are all wrong. But apparently it takes an English major to see that they are wrong.

The key point of the stanza is that "The brain is wider than the sky." How so? Because, Emily says, it "includes" the sky. And, she adds as a kind of afterthought, it includes "you" as well. Clearly she is implying that the brain includes "you" -- the self -- in exactly the same way that it includes the sky. So if that means that the self is a function of the brain, as Paul asserts and as he believes, then it would also have to mean that the weather is a function of the brain (which I am pretty sure he does not believe). In other words Paul's reading of the poem is absolutely and irrefutably NOT what the poem could possibly mean, NOT what Emily could possibly have meant to say. And this is even more apparent if you look at the rest of the poem:

The brain is deeper than the sea,

For, hold them, blue to blue,

The one the other will absorb,

As sponges, buckets do.

The brain is just the weight of God,

For, lift them, pound for pound,

And they will differ, if they do,

As syllable from sound.

I read this as saying that the brain is the physical expression (weight) of the spirit of God. So that would make the self a function of God, something that permeates the brain in the same way that water permeates a sponge.

So what am I trying to prove here, that I was an English major and Paul wasn't? No. I'm trying to make the point that neuroscience can be dangerous, especially in this "age of the brain," because it can easily seduce us into missing the forest for the trees, limiting the horizon of our understanding to things that can be studied in a laboratory experiment. Freud made a similar point in his autobiography where he described the relationship between psychoanalysis and neuroscience in the 1890s:

"...[T]he direction taken by this enquiry was not to the liking of the contemporary generation of physicians. They had been brought up to respect only anatomical, physical and chemical factors.... They obviously had doubts whether psychical events allowed of any exact scientific treatment what-ever... Even the psychiatrists, upon whose attention the most unusual and astonishing mental phenomena were constantly being forced, showed no inclination to examine their details or enquire into their connections. They were content to classify the variegated array of symptoms and trace them back, so far as they could manage, to somatic, anatomical or chemical aetiological disturbances. During this materialistic or, rather, mechanistic period, medicine made tremendous advances, but it also showed a short-sighted misunderstanding of the most important and most difficult among the problems of life."

The uses of literature .... and history

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2003-10-06 22:10:01

Link to this Comment: 6816 |

Its always a pleasure to have Elio around. One can reliably count on erudition and ... combativeness. I freely admit I was not an English major. Whether that puts me at a disadvantage in reading Dickinson I will leave others to decide. I will though insist that it is not MY fault if Gerald Edelman happens to share my interpretation and that my agreement with him on that score does not necessarily imply agreement with him on any others.

Despite being a biology major, I actually like both the Bible and Freud. As stories ... written by interesting and wise people ... many years ago , And hence as inevitably not taking into account additional observations made over the years since those that motivated the stories.

To put it differently, I'm interested in what stories make sense NOW, and take it as a given that they are likely to be (indeed OUGHT to be) different from the old ones.

Sure "neuroscience can be dangerous". So too can Freud and (forgive me) the Bible (which is not well know for its recent history of expanding "the horizon of our understanding").

Psychoanalysis, I would suggest (to meet fire with fire) is ALREADY "in big trouble". And I don't think its going to get out of that trouble by trying to prove that studies of the nervous system are either irrelevant (they aren't) or ungodly. More importantly, I don't think we're going to have an effective mental health care system so long as psychoanalysis and neuroscience are warring with each other (cf Of Two Minds). Both psychoanalysis and mental health care have a better shot at success if we can collectively turn our attention to what it is that psychoanalysis and neuroscience have to offer each other. Which is, I'm pretty convinced, quite a lot.

Another Useful Model

Name: Daniel MA

Date: 2003-10-09 20:34:04

Link to this Comment: 6871 |

Before Freud, before Shakespeare, and before the birth of 'science,' the ancient Chinese offered a perspective that has been handed down through the centuries and that may be useful for contemplating our multiply-dimensioned quest for understanding.

The Chinese story of "The Blind Men and the Elephant" goes beyond the polarization of an adversarial (enemy) perspective as opposed to affiliative (acquaintance or congruent bedfellow) perspectives described in our title.

Everyone is familiar with this story: One blind man (grasping the elephant's leg) decided that an 'elephant' is a tree trunk. Another (grasping the tail) declared that an 'elephant' is a broom. Still another (grasping the trunk) determined that an 'elephant' is actually a fire hose. Et cetera.

What none of these thoughtful men, searching for knowledge and groping toward the unknown, adequately understood was how incomplete (albeit valid) their observations were, and how little they actually understood. Despite making careful observations and obtaining relevant data, none could comprehend the outlines of the 'whole' entity, nor understand how the parts they were exploring were interrelated and related to the total system. Although each man thought that he could be sure of the correctness of his conclusion, none understood the essence.

Some vantage points and observations may even focus upon portions of the totality that aren't necessarily 'congruent' with, or particularly relevant to, one another. For example, whereas each of the elephant's legs does have congruence with and relevance to the functioning of the other legs, the tail and the trunk have little congruence or relevance to one another.

Thanks for a stimulating conference!

Danny Freeman

The Uses of Literature, continued

Name: Anne Dalke

Date: 2003-10-10 12:46:04

Link to this Comment: 6877 |

I attended the panel presentation on Psychoanalysis and Neuroscience last Wednesday night, and was intrigued by Susan Levine's closing quip that she was following good psychoanalytic practice by "denying gratification" to all those still waiting (it was testimony to the interest generated by the conversation that there were quite a few of us still waiting) to ask questions. I wonder if Susan (or someone else who is a psychoanalyst) could explain her observation to me. Was she simply gesturing toward what is commonly acknowledged among literature professors: that narrative will always exceed analysis, that interpretation will always be "belated," always lag behind, always be but an incomplete-inadequate-and-unsatisfactory account of what has happened? Or is there a pointed psychoanalytic understanding expressed in the principled "refusal to gratify"?

I actually have a couple of other questions I'd be gratified to have addressed, should anyone have the interest/inclination. I was particularly struck by the shared use, in the essays Elio, Syd and Paul posted prior to their presentations, of the key word "experience," of their repeated insistence on the importance of "what the mind is experiencing." It seemed to me that, despite the shared valuing (actually: valorization) of the term, each of you was using it to mean something different. When you say "experience," are you referring only to what we are conscious of? Only what we know we know? (I'm drawing here on a very interesting conference I had with a student yesterday, who told me of a rubric she'd learned from a course at Penn on "writing memory"; the prof drew a quadrant, composed of

- what you know you know

- what you know you DON'T know

- what you DON'T know you know, and

- what you DON'T know you DON'T know.

Is experience, as each of you describes it, only what we know we know (plus, perhaps, what we know we don't know)? Or does (and if so, HOW does) it encompass/intersect with the other quadrants?

All of this is preparatory to circling back to my own professional community, those who earn their livings (more importantly: find their meanings) by writing/reading/studying/interpreting literature: the site where "what it feels like on the inside" has been so often and so well represented, and which of course also has contributed thereby quite a bit to conversations about and understandings of mental health and illness. I've never much liked Emily Dickinson's "The Brain--is wider than the Sky" (or rather, I've never much liked that gesture, @ the end of the first stanza, in which she so "easily contains" "You"--which I understand as ME, the reader--within her own brain). Is that comparable to what Susan is talking about in her upcoming essay "On the Experience of Having an Other"?....

Anyhow: ED has at least twenty poems in which the brain engages in all other sorts of intriguingly quirky behavior. The brain "laughs" and "giggles" and "bubbles cool" in her poetry, and is very hard to repair, once damaged:

The Brain, within its groove

Runs evenly--and true--

But let a splinter swerve--

'T were easier for you--

To put the current back --

When floods have slit the hills--

And scooped a Turnpike for Themselves--

And trodden out the Mills--

A number of ED's brain-poems are very acute descripions not only of the immense capacity of the brain, but of its materiality and--most striking to me--its bipartite quality. A few of them meditate on the difficulty of knowing the brain of another--"whom we can never learn"--but the poems most clearly prescient for our 21st-century conversation about the complexities of brain activity are those with a very striking sense of a self divided, a self conscious of its unconscious processes. Paul and I actually played, a few years ago, with the notion of writing an essay about ED's unusual brain poetry; we didn't get very far, but I've just uncovered my notes from that short bout of thinking. You can find The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson on-line. I also extract and offer here, as gifts to each of the Wednesday night panelists, and for anyone still listening in the audience, three of the most astonishing, most "psychoanalytic," and (to me) most interesting contributions to our contemporary exploration of these matters.

First for Sid, because he's written so powerfully about the the difficulties of understanding "memory organization" when one models the brain "topographically":

I felt a Cleaving in my Mind--

As if my Brain had split--

I tried to match it--Seam by Seam--

But could not make it fit.

The thoughts behind, I strove to join

Unto the thought before--

But Sequence ravelled out of Sound

Like Balls--upon a Floor.

For Paul, who briefly fancied himself a Texas Ranger, ED offers this account of the horror of meeting oneself in a (non-?) material place:

One need not be a Chamber--to be Haunted--

One need not be a House--

The Brain has Corridors--surpassing

Material Place--

Far safer, of a Midnight Meeting

External Ghost

Than an interior Confronting--

That Cooler Host.

Far safer, through an Abbey gallop

The Stones a'chase--

Than, Unarmed. one's a self encounter--

In lonesome Place--

Ourself, behind ourself, concealed--

Should startle most--

Assassin hid in our Apartment

Be Horror's least.

The body--borrows a revolver--

He bolts the Door--

O'erlooking a superior spectre--

Or more--

And finally, for Elio, for obvious reasons, the one moment when Emily allows for the existence (and importance) of a soul separate from brain:

If ever the lid gets off my head

And lets the brain away

The fellow will go where he belonged--

Without a hint from me,

And the world--if the world be looking on--

Will see how far from home

It is possible for sense to live

The soul there--all the time.

Further literary analysis, anyone?

Wednesday evening

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2003-10-10 16:50:39

Link to this Comment: 6880 |

My thanks to all involved for an enjoyable and stimulating

discussion Wednesday evening. It was good to have Bruce remind us that Freud was in fact originally a laboratory neuroscientist, and left an unfinished

Project for a Scientific Psychology. I was, by coincidence(?), browsing

An Autobiographical Study and picked up an additional tidbit suggesting that Freud would probably have had less trouble dealing with neuroscience than some modern psychoanalysts do. To wit:

"I should have been very glad if I had been able, later on, to make a psycho-analytic examination of some more cases of simple juvenile neurasthenia, but unluckily the occasion did not arise. To avoid misconceptions, I should like to make it clear that I am far from denying the existence of mental conflicts, and of neurotic complexes in neurasthenia. All I am asserting is that the symptoms of these patients are not mentally determined, or removable by analysis, but that they must be regarded as direct toxic consequences of sexual chemical processes"

It sounds to me like Freud's available observations were such that he wouldn't have been entirely relucant to make use of chemical therapeutics in at least some cases and contexts. The fragment resonates as well with our efforts to clarify the concept of two interacting systems, and the broader concern to try and understand the place of psychoanalysis in the more general task of improving mental health care for all.

I thought I'd try and set down here a few of the other issues and thoughts that made the evening a stimulating and productive one (for me at least), despite being acutely aware that it can't not but be my own story (and so hopeful that others will add their different ones)

Elio's bashing of the "Freud-bashers" was, of course, neither unexpected nor unwelcome. What was somewhat more surprising (and gratifying) was his acknowledgement that there could/might be "good neuroscientists" to counter the bad. Surprising or not, Elio's first point remains an important one. There IS a real and present danger that contemporary trends will further militate against the practice of longer-term "talk therapy". I think this has more to do with unresolved issues within and among psychiatry (cf Of Two Minds), psychoanalysis, psychology, and social work, as well as broader social trends (aspirations for security, insurance, managed health care), than it does with neuroscience. Regardless, the important question is whether this unfortunate trend (unfortunate in my mind/brain at least) is more likely to be reversed by attacking neuroscience or by trying to build an alliance between psychoanalysis and neuroscience (and others). I'm inclined to think the latter, and, like Syd, I'm inclined to think the latter is possible (indeed I think its already beginning to get underway and would like to see our conversation as a part of that effort).

There was an interesting difference of opinion between Elio and Syd about Eric Kandel's role in this process. I'm not going to cast a vote here. My life as a young scientist was a little too entangled with that of Eric as a more senior figure. It is though worth noting that Eric was a psychiatrist and had aspirations to becoming a psychoanalyst before becoming a "neuroscientist" (a Freud inversion?). If nothing else, that's another indication that similar interests may draw people into either psychoanalysis or neuroscience and hence another reason for believing the two lines of inquiry are similar enough to provide common ground for productive interaction.

Syd's suggestion that we could work toward "congruence" made sense in these terms. To me at least. If indeed Emily Dickinson was right (as I interpret her), then of course the theoretical/conceptual structures used by psychoanalysis and neuroscience can each be usefully modified by comparison with the other, and will progressively converge. After all, the theoretical/conceptual structures are efforts to tell useful stories about the same thing: human behavior and one's experience of it. A key question here, of course, is whether neuroscientists are willing and able to include "one's experience of it" within their domain of inquiry. Some of us certainly are already (cf Antonio Damasio's The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness, and my own The Brain's Images: Co-Constructing Reality and the Self), and my sense is more will inevitably find their way there. The converse questions are whether psychoanalysts will be welcoming, and whether they will in turn be interested in and regard as relevant to their concerns the stories neuroscientists have to tell about our more extensive explorations of other parts of the nervous system.

Along these lines, I thought that the issue of whether the "neurobiological unconscious" is or might become the same thing as the "psychoanalytic unconscious" (raised both by Syd and several audience participants) was one of the the questions that arose during the conversation that most warrants some serious and focused further consideration. My own sense, as a neurobiologist, is that there is very little difference between what goes on in filling the blindspot, in a number of phobias, and in transference and counter-transference; they all involve things going on in the unconscious part of the nervous system without information about them being conveyed to conscious processing. At the same time, there are clearly some practical differences among these things, and there may be important neurobiological ones as well. The "topography" of the unconscious is still, I gather, a matter of debate within the psychoanalytic community, and certainly is not fully worked out within the neuroscientific one. My guess is that some "congruence" efforts in this realm would be quite productive.

Pleased as I am to endorse and enthusiastically participate in efforts to achieve "congruence", there remains for me something just a bit wary and standoffish about it, particularly in the context of Syd's "astonishing clinical irrelevance of the neurosciences". My fantasies still run to something a little more intimate. It was for this reason that I was pleased/delighted with Elio's offering of Hamlet as a candidate for a comparison of clinical approaches as they emerged in the mind of a psychoanalyst and a neuroscientist (yes, of course, a PARTICULAR psychoanalyst and neuroscientist, and so "not necessarily the opinions of the sponsors").

I suspect Elio wouldn't want to have to defend a therapeutic procedure conceived in the absence of more extensive engagement with the patient (and know I wouldn't), but there were some general differences in approach that suggest why a more intimate relationship between psychoanalyst and neuroscientist might be productive in dealing with the unconscious, not only theoretically but practically. For a neuroscientist, the unconscious is neither pristine humanity nor raging lust, just as the conscious is neither; both are mixes of both (and a few other things), but the two handle them in quite different ways (trying to characterize how these styles are different is one of my current preoccupations). And depression is ... an adaptive response? needed suffering? conflict? paralysis? boredom? or a failure of the unconscious to communicate with the conscious? Which should be treated .... how? Think or feel or act ... or some combination of the above? I suspect what we need is a few brave neuroscientists who are willing to let some brave psychoanalysts into their laboratories, and a few brave psychoanalysts who are willing to let some brave neuroscientists into theirs.

The other particularly generative issue (for me) arose at the very end of the conversation. Susan asked "Is psychoanalysis science or hermeneutics?", with the thought (I think) that the answer to that question was needed to decide whether an alliance between psychoanalysis and science was in fact possible. My own feeling is that that question presumes that one already has at hand a particular answer to a prior question: "Is science science or hermeneutics?". And my answer? See, treating the probelm probably at perhaps more length than some will want , Getting It Less Wrong, the Brain's Way: Science, Pragmatism, and Multiplism . In short form, being a neuroscientist inclines one to argue there is much less difference between science and hermeneutics than many people (both scientists and non-scientists) think .... which may be why I think that neuroscience and psychoanalysis are actually closely related , and could easily be more so?

One man's story ... of what has been, could/might be? Very much looking forward to what others saw/heard/thought, and, perhaps to this forum and the associated website continuing to play a role in moving us in positive directions. There is, among other things, a resource list on the website; suggested additions to that list can be posted here or sent to me by email for addition. Let's see what we can keep rolling in the way of a conversation and resource list. In our own interests, and in the interests of mental health care generally (see Mental Health on Serendip).

alter(ity)?

Name: Anne Dalke

Date: 2003-10-12 14:30:34

Link to this Comment: 6888 |

Would like to pick up here on Paul's musings that there is much less difference between science and hermeneutics than many people (both scientists and non-scientists) think ....

To do so, I went first to the OED, where I found "hermeneutics" DEFINED as "the ART OR SCIENCE of interpretation, esp. of Scripture. Commonly distinguished from exegesis or practical exposition." The etymology of the word actually goes back to 1737, and the OED takes it forward to 1967, when J. MacQuarrie suggested, in God-Talk, that "history is the hermeneutic of historical existence," "physics...the hermeneutic of nature."

If, as this definition suggests and I think useful to presume, ALL inquiry is an act of interpretation, then clearly psychoanalysis and neuroscience (and literary interpretation, and art history, and chemistry, and...) are aligned. I was thinking about this alignment again last night, as I was talking w/ my son Sam (a freshman at Haverford, home this week for fall break). Sam's taking a course on "Global Wisdom," and has just finished reading some of the Platonic dialogues. After he reviewed for me the concept of Ideal Forms ("triangle-ness" and "table-ness," etc.), we got into an interesting discussion about where change comes from. If, as Plato said, all we are doing is perceiving what is already there, where's creativity come from? Where does newness arise? How can one alter what IS--including unhelpful/pathological patterns in one's own brain? Sam and I ended by acknowledging both that there IS a world existing independently of us (if I say to the tree, "drop your leaves," or "rise up and walk," the tree will not alter its behavior) AND that we can act to change it/ourselves. If we don't actually CREATE it/ourselves, in any primal way, the accounts we give of it/ourselves--the interpretations we provide--can be small contributions towards changing its shape, and our own.

But perhaps THIS is where "neuroscience" and "psychoanalysis" diverge? That the former is seeking "only" to describe what is (the patterns of interactions of neurons, etc.), while the latter aims to "cure," to alter, to CHANGE what is...? I've just finished Keith Doubt's 1996 Towards a Sociology of Schizophrenia: Humanistic Reflections, a critique of post-modernism's tendency to valorize the mentally ill (in particular, to use schizophrenia as a metaphor for the human condition). Doubt (a striking name, in this context!) constructs his critique by using the terms of George Herbert Mead (Mind, Self and Society, 1934): "me" is the attitudes of others, which oneself assumes; "I" is "what we cannot tell in advance," that which "gives the sense of freedom, of initiative," is "never entirely calculable." According to Mead, it is the "social process" of these two distinguishable phrases ("conscious responsibility" and "something novel in experience") which constitutes the self. When the "me" co-opts the "I," it's a tragedy (shades of Hamlet?); when the "me" can't cut or tie "I," it's a comedy. Whatever the genre, it is the synthesis/reflexiveness/dialectic between the two which make up the grounds of identity and self-development.

I hear in this argument strong resonances both to a recent conversation in the Making Sense of Diversity Series: "Asian--Identity or Category?" and to the on-going Brown Bag discussion about What Counts? in which we are interrogating in particular whether the numbers we use to "count" the world reflect what actually IS or what we ASCRIBE to what is...

and whether (in either/both cases) we can alter what it is we are interpreting here.

Comments re Freeman and Dalke's posts

Name: Sydney E.

Date: 2003-10-12 20:04:10

Link to this Comment: 6890 |

I enjoyed being in the Panel, and would like to make a few additional points.

First, in response to Danny, I don't think that 'congruence' means a point-by-point agreement on every aspect of the phenomena being studied. As Danny points out, there will certainly be aspects of the mind that psychoanalysts study that neuroscientists probably have little to say about (the content of specific fantasies, for example), and the same goes for neuroscience (the areas in the brain that those fantasies activate, perhaps). Congruence just means that we have to be as clear and specific as possible as to what we are talking about, and each side has to take into account (as far as possible) the findings of the other side when they are talking about something that is overlapping. Old psychoanalytic affect theory, which holds that affects are 'discharge processes of instinctual drives', for example, is not congruent with the extensive research done by neuroscience on the way affects are activated in the brain. Faced with that incongruence, psychoanalysis has modified its theories about affect in a way which is by and large congruent with neuroscientific findings. I hasten to say that psychoanalysis began this modification on clinical grounds, long before neuroscience showed that such modification was necessary, but the neuroscientific findings spurred us along. Now the two fields have a theory of affects which do not contradict each other. That is, they are congruent.

To keep this readable, I'll just respond at this point to Anne Dalke's first question: "is there a pointed psychoanalytic understanding expressed in the principled "refusal to gratify"?" Susan was referring to an old principle of psychoanalytic technique which held that unconscious wishes should not be gratified in the psychoanalytic situation. Freud found early on that patients come to desire a lot of things in their analysis, many of them based on early wishes for those things from their parents. They want to be their analyst's 'only child', for example, or (horrors!) they feel that sleeping with their analyst will cure them. He also found that at least some of the early analysts were trying help patients by sleeping with them. His advice basically was that those wishes should be understood, not gratified, and this was generalized to the principle that there should be no gratification, just understanding. That principle got transmogrified into an absolute, resulting in the worst case in the caricature of the silent analyst who didn't particpate in the relationship at all except for a rare interpretation. Now we know that the gratification of some wishes is inevitable, and, indeed, desirable. The wish to be understood, for example, must be gratified. It's an essential part of the analytic relationship. So, the dictum of 'no gratification' has fallen by the wayside, although we still try to understand what our patients are yearning for, and to help them understand it.

More later.

Cordially,

Syd Pulver

spulver@bellatlantic.net

painting the conscious & unconscious

Name: Sharon Burgmayer

Date: 2003-10-13 09:40:50

Link to this Comment: 6891 |

A couple of ideas have followed me around since Wednesday's panel discussion. I've been musing on the relationship between the mind and the brain, something introduced by Elio during his segment. And, like

Paul , I remain intrigued about the "topography" of the unconscious and about the idea of whether there are multiple unconscious: a neurobiological one and a psychoanalytic one.

Since my brain prefers to express in pictures and images, rather than in words, it began playing at a search for representations to describe the dualities of brain/mind and conscious/unconscious. The brain is not the mind, yet they are obviously related. The brain is ... the house and the mind is ... what is happening within it? The brain is clearly a material, objective thing while the mind is certainly (at least to me) not material, not a thing. Perhaps the mind is all dynamic—action, events, processes—the collection of events at any instant. In this view there would be no "mind-as-a-thing" to experience anything.

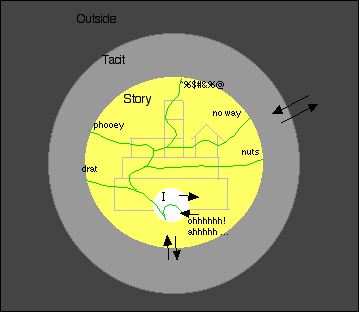

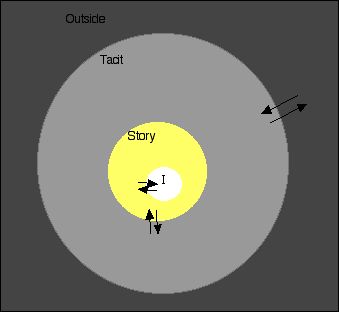

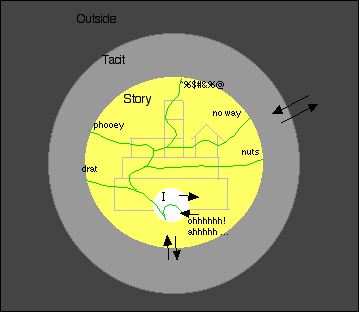

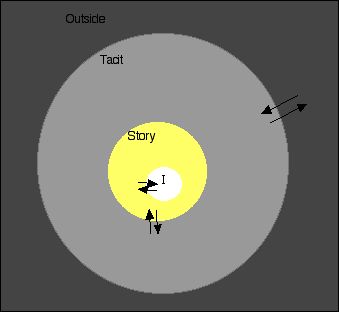

The mind seems most often to connote conscious brain activity, but of course, it must be informed by the unconscious as well. Both conscious and unconscious information and processing occurs in the brain, in the same space, but in such different ways that makes them seem distinctly compartmentalized. How do these differ? That was the key question that got my brain to play at painting a picture that contains the conscious and unconscious.

So I came up with an image to distinguish conscious and unconscious processes. This image paints the conscious as a network with nodes (with rather unfortunate similarity to the typical image of the neural net). Conscious processes travel as energy on along a network path, following internal instructions* to "turn right, turn left, go straight", thus constructing the thought as certain paths and segments are followed and connected. The unconscious is superimposed on this neural network (since the unconscious seems to have access to the same regions of the brain) but it does not follow the networked paths. The unconscious uses some entirely different process—different, by analogy, like teleportation is to normal travel—to make connections between the different regions of the brain. Unlike conscious activity that appears to be linked to language, the unconscious navigates ("teleports") using images whose form, color and emotion "code" locations in the network thereby making connections between brain regions in a completely different way that remains invisible to the conscious.

Pursuing this admittedly wacky image prompted further ideas and questions: So, is the mind is the summation of both activities in the network, path-travel and teleportation? Perhaps it is when the "teleported" energy of the unconscious intersects (collides with) the conscious energy traveling along the network paths that we experience those too-rare occurrences of sensing the activity of our unconscious? Does psychoanalysis increase the mind's alertness to those moments of such intersection? Perhaps what neuroscience detects are the network paths and sometimes travelers along them but has missed—or does not yet have the tools to detect—the unconscious' mode of making connections when it "teleports" around?

Another more obvious picture gives the conscious and the unconscious each their own elaborate network, both which largely do not intersect with each other. My intuition finds that less appealing, I suppose, because the image fail to explain the invisibility and the very different functioning of the unconscious as compared to conscious.

Fantasy? Of course. But how many times has fantasy preceded discovery and development?

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

* the "what you know you know, what you know you don't know" in Anne's terms

begging to differ

Name: Elaine P.

Date: 2003-10-13 10:43:55

Link to this Comment: 6892 |

This is to follow on Anne Dalke (hi Anne) and Elio and Paul on the Dickinson poem and matters psychoanalytic.

I am intrigued by the way in which the neurosciences get privileged as a necessary adjunct (or enemy) of psychoanalysis and then poetry gets pulled in as a way of contesting and establishing "meaning".

The Dickinson poem intrigues me (another English major) for a number of reasons. For one, her syntax is deliberately indeterminate; the brain can encompass (and name) the sky and the sponge and the bucket just as readily as the bucket can contain the sponge and the water. The "you, beside" at the end of the last stanza can be read as Anne does, as "you, as well" including "you" in my brain. It can also be read as "you, apart from" or "you, to the side", introducing the subjectivity that is,or always perceives itself to be, in a condition of differentiation from that which is perceived. This interpretation makes sense to me when I consider the lines,"and they will differ, if they do/ as syllable from sound." What difference obtains between a syllable and a sound, is in the space between them, the introduction of necessary gaps and silences so as to allow syllables to emerge from sound. This analogy preserves a space, even if imaginary, around each subject, as around each word, that is constitutive and, in itself,resistant to interpretation.

On Anne's quadrants, then, I would only point out that the last possibility, that we don't know what we don't know, would serve as a continual disruption or undermining of the first quadrant, that we know what we know. This dynamic sense of an unconscious operation is, for me, the realm of psychoanalysis.

On the gratification of psychoanalysis, I would add to what Syd said, that making an interpretation can be more gratifying to the analyst than the analysand; can, in fact, be analogous to the brain of the analyst containing the 'you' of the analysand in the way Anne objects to in the poem. Denying gratification in this sense, then, would be to the point of maintaining the "differ"-ance between the two, so as to allow the words, and subjectivity, of the analysand to emerge.

Finally, I'd like to quote from Lacan's "Function and field of speech and language" :

"The list of the disciplines named by Freud as those that should make up the disciplines accesory to an ideal Faculty of Psychoanalysis is well known. Besides psychiatry and sexology, we find 'thehistory of civilization, mythology, the psychology of religions, literary history, and literary criticism'....For my part, I should be inclined to add: rhetoric, dialectic inthe technical sense that this term assumes in the Topics of Aristotle, grammar, and, that supreme pinnacle of the aesthetics of language, poetics, which would include the neglected technique of the witticism....For psychoanalysis in its early development, intimately linked to the discovery and study of symbols, was on the way to participating in the structure of what was called in the Middle Ages, 'the liberal arts.'...But we should not disdain this aspect of the early development of psychoanalysis; it expresses in fact nothing less than the re-creation of human meaning in an arid period of scientism."

Gratification, clinical and literary

Name: Susan Levi

Date: 2003-10-13 11:45:15

Link to this Comment: 6893 |

Yes, gratification does have a rather specific meaning within psychoanalysis, as Syd has noted. I also think it may well be related to your comment about literary interpretation as always being incomplete in the sense that the Lacanian understanding of desire includes the idea that desire can never be satisfied.

My comment about the non-gratification of the audience's wish to ask questions the other night was an ironic nod to a classical position to which I do not subscribe. The notion of gratification in clinical psychoanalysis refers to the principle that if the patients' wishes are not gratified by the analyst then the wishes will have no place to go but to the verbal arena where they become grist for the mill. The idea was that if the analyst gratifies a wish, then, the early analysts thought, it is no longer available to be worked through in the treatment. The wish usually has to do with wanting to know something about the analyst or wanting something from the analyst, neither of which the analyst is supposed to gratify (according to orthodox clinical practice). The most essential meaning of non-gratification has to do with actions: the analyst does not touch or have sex with a patient who want to be touched or had sex with with. This clinical principle was also understood to extend to such practices as not answering questions posed by the patient. Thus, the parody of the silent analyst.

There is now a more sophisticated understanding of these issues. As Jay Greenberg puts it, "Consider the standard injunction, 'Don't just do something, sit there!' That is often good advice, but the implication is that it is possible to do nothing, which seems unlikely to me. . . . ." (Greenberg, J. (1995) "Self-disclosure: is it psychoanalytic?" Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 31,2: 193-205.) In other words, the analyst is always gratifying some wish, and he/she must be aware of this and try as much as possible to understand with the patient what has happened between them and what it means. (Just to be completely clear, I want to state that gratifying a patient's sexual desires is absolutely unethical.) When silence and not responding to a patient's questions are excessive, it creates not a neutral situation in which the analyst and patient may discover the patient's unconscious material but rather a contrived situation. By not answering questions, for instance, the analyst may be gratifying the patient's masochistic aims.

If one believes in the power of the unconscious, then it is clear that it is truly difficult to prevent the patient's unconscious fantasies, desires, fears, and efforts to reenact traumatic situations to emerge in the treatment situation. As long as the analyst is relatively neutral and anonymous and does not consistently act in such ways as to block the patient's self-expression, then the unconscious will do its thing and the treatment will progress. And, following Lacan, desire will always remain unsatisfied and will continue to press for satisfaction. Or, to paraphrase Jerry Seinfeld, "I don't have to worry about spoiling my appetite because I know there's always another appetite coming along after this one."

gratification and beyond ...

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2003-10-13 21:07:40

Link to this Comment: 6895 |

Re Syd, Susan:

The gratification issue, as it plays out interpersonally, has bedeviled psychoanalysis since before its official birth. Freud broke with Breuer, his first serious collaborator, because of related sexual hanky-panky (on Breuer's part, not Freud's, at least according to Freud). And, as noted, there have been major course adjustments within the psychoanalytic community over the years and are likely to continue to be.

An interesting more general question, for me at least, is what one can learn from this ongoing evolution for broader issues of mental health care? Are difficulties in negotiating what needs will and will not be addressed by whom and when idosyncratic to the psychoanalytic setting or are they more generic? They are clearly not specific to the sexual realm, but perhaps to the interpersonal one?

For what its worth, my own reading of Susan's closing comment had to do not with frustration but rather with my understanding of the psychoanalytic "hour": an interval of time which is defined in advance (and adhered to) in order to avoid any expectation (on the part of either analyst or analysand) that some problem is going to be discussed until it is solved. Such expectations would detract from the open-ended exploratory character of the enterprise. In these terms, perhaps the gratification issue isn't even essentially interpersonal? Perhaps intra-personal conversation similarly requires a sense of open-endedness (rather than a problem-solving bent) for its success? In re many mental health contexts, not only in psychoanalysis?

Re Sharon:

Sharon is a colleague in chemistry, a painter, and the person who asked me several years ago, what DOES the world look like to the unconscious? (given that what WE see is only the painting after the fact, after the blindspot is filled in and etc). Sharon and I have been playing with that question for some time, her in art and me in .... whatever my medium is called. The image to the right is one of Sharon's contributions to the discussion (other images, related and unrelated, are available at Transformation).

Two things strike me as interesting about Sharon's current thoughts. One is that she identifies here networks as the "conscious" whereas in her earlier painting the networks seemed (to me at least) to represent the "unconscious" with the view as we actually see it above. The other interesting aspect of Sharon's image (at least in words) is that she identifies networks as rule-bound and hence needing some magic "teleportation" to account for some of the things invisible/surprising to the conscious.

What amuses me about this is that in my current understanding/story, it is in fact one of the important properties of network information storage that "teleportation" is inevitable, and hence not a surprising property of the unconscious. Because networks do not "code" things in particular locations but rather in the pattern of activity across the entire network, there are in fact quite natural ways for one thing to be closely related to another thing, even quite distant things from the perspective of the conscious which is more used to "categorizing". The distinction is one between metonymic and metaphoric forms of representation (see Theorizing Interdisciplinarity: Metaphor and Metonymy, Synecdoche and Surprise, and Story-Telling in (At Least) Three Dimensions). What this particular story raises as a new problem is why the conscious (presumably also consisting of neural networks) DOESN'T "teleport" (or at least doesn't as often)?

So how SHOULD one think of the unconscious, and its relation to the conscious? Sharon's way, my way, or .... ?

Re Daniel, Anne, Elaine, and others past/present/future

Delighted to have elephants (a favorite of mine, both in "reality" and fable), hermeneutics (fine by me as long as not restricted to the interpretation of human artifacts, and having some way to distinguish more wrong from less wrong), and Lacan (as long as somebody will interpret it for me) on the table. Suspect, in fact, that we could use more on the table to help make sense of what's already here. Along with some further conversation about existing issues. To facilitate that:

- Visitors are more than welcome to join in, whether they were around for the Wednesday night panel discussion or not. The issue on the table is the relationship between psychoanalysis and neuroscience, in the broader context of how to improve mental health care in the United States (and the world?).

- If you click on "Keep Me Posted" and follow the instructions, you'll get an email message any evening when there have been new postings here. It will include a link to the forum so you don't have to remember the URL or remember to check back here to see what new might have happened.

- Some people (to remain unnamed) have been reported to be experiencing html-envy because some postings (like this one) have pictures and links. Don't be put off by that. Pictures and links are a bonus, not remotely a necessity. And, if you're inclined, you TOO can use html. If you want to link to another message in this forum, just follow the instructions provided in the last but one paragraph in the posting window (which turns up when you click on "Post a comment"). If you know something of html already, feel free to use it (but be sure to click the Preview button in the posting window to be sure you've appropriately used and ended html commands). And if you want to learn some html, there's a link in the last paragraph of the posting window instructions that will get you started, and you can use the Preview function to try it out and play around.

Gratified by the conversation so far, and looking forward to it continuing, both virtually and in whatever other arenas people are inclined to develop.

Power Games

Name: Anne Dalke

Date: 2003-10-14 12:51:29

Link to this Comment: 6896 |

Powerful to me, in the postings foregoing, are Syd's description of "trying to understand what our patients are yearning for," and Susan's replacing the (now-outdated?) notion that "the gratified wish is no longer available to be worked through in the treatment" with the (more current?) understanding that "desire will continue to press for satisfaction..."

It's been so rich to have had so much more "put on the table" since last week's panel session...

but I'm not gratified yet. Each satisfaction seems only ground for yet another "appetite"....

so/and I wanted to go on thinking, this morning, not by (as Elaine noticed) "pulling in poetry as a way of establishing 'meaning,'" but rather by using Sharon's pictures (which have been SUCH a rich resource for me, over the past couple of years, in understanding/perceiving the loopy relationship between conscious and unconscious understandings) to gesture towards (actually, I think, BEYOND) further understandings of the relationship between neuroscience and psychoanalysis...

Contra Paul, I think Sharon has ALWAYS painted (for years in watercolors and this week in words) the conscious mind as a box/network/grid, and the unconscious as its creative explosive expression. This week she described the brain as a house and the mind as "what is happening within it," also "the conscious is a networked path and the unconscious teleportation." But her pictorial representations of this relationship go back to 2000, when she first showed that

"Understanding is a Booby Prize"; include her portrayals of the emergence of

"Creation" and of its

"Power"; as well as her more recent SO-powerful representation of the

"Interface"

of "feeling and thinking " (where I see Emily Dickinson's creative/"cleaved"/"split"/"unraveled"/ "haunted" mind, w/ its "lid lifted off," drawn large).

Struck again, as I walk through her gallery, by the force of Sharon's paintings, I am reminded of my husband's resistance, each morning, to my desire for an interpretation his (equally striking) dreams: there is an experience there, he claims, that cannot be contained, that can only be--that is ALWAYS--reduced, by the analysis. Shades of Elaine's notion that "making an interpretation can be more gratifying to the analyst...can be analogous to the brain of the analyst containing the 'you' of the analysand..."

Anyone want to chew on/dig into that mine/line of thinking, pictorially, poetically, analytically, scientifically....??

Free associations

Name: Elio Fratt

Date: 2003-10-18 10:16:02

Link to this Comment: 6914 |

There are enough threads in the messages posted so far that a consciousness seeking some kind of integration or even some kind of coherence really couldn't know which way to turn along the network of ideas (let alone neurons) that have been expressed so far.

I have a hard time imagining how this discussion could ever evolve into a discussion (let alone an implementation) of how psychoanalysis and neuroscience can work together to improve the mental health care system, which I understand is Paul's ultimate agenda.

The phenomenon that feels to me like teleportation (magic, unexplainable by science as we will ever know it) is that forever-mysterious leap from the neural network and/or the neural energy field to conscious awareness ("bare attention" as the Buddhists say) and the equally mysterious leap back. We can say metaphorically that a consciousness tries to find its way along a neural network but unless we stop to look at the meaning we assign to the metaphor, we won't notice that it has quietly collapsed a mystery into one of two assumptions: either that consciousness is some kind of neural homunculus that lives right next to the on-ramp of the network or that consciousness is an "I" that is outside the neurally networked "Me" in much the same way that I am currently outside the computer that is compliantly receiving and transducing the impression of my ghostlier-than-a ghost thoughts.

I didn't understand what Anne said that Doubt said that Mead said about the Me and the I, but there's something in there that I probably agree with. "Me" certainly does include the instructions (learning) "I" receive from the world about how I/Me am and should be, but it also includes the instructions "I" receive from my genes and from my neurally encoded affects, dispositions and drives (whether genetically programmed or not) and from whatever modifications "I" have managed to make along the way to these assorted environmental/biological instruction sets by dint of my freely deconstructive will. "I" am somebody else again, possibly related to the I who am who am.

Having said that, when I think about Hamlet it becomes clear to "I" that "I" must be more than who I know I am, and so must "Me" be. The aspect of Hamlet's Me coopting his "I" would seem to be his impulsive "drive" for revenge PLUS the ghost of his father and his culture conspiring to coopt his freely deconstructive will. But then what in the world is his depression that can presume to interfere with this mighty "Me"? An ""I"" that his "I" doesn't know about instructing a ""Me"" that coopts the "Me" that is trying to coopt his "I"? More things in I and Me than are dreamed of in your philosophy, Horatio. Enter Prozac (standing in for Rosenkranz and Guildenstern who, in this post-modern performance of Hamlet, appear to be dead), stage left.

Psychoanalysis is first and foremost about inner conflict because, as Emily Dickinson understood from her own experience, the root of human suffering is inner conflict. In that sense schizophrenia IS a metaphor for the human condition. Conflict between the flesh and the spirit. Conflict between feeling and thinking. Conflict between feeling and acting. Conflict between thinking and acting. Conflict of the "I" with the "Me," of the "I" with the ""Me,"" of the ""I"" with the "Me," of the ""Me"" with the "Me." If psychoanalysis and neuroscience are to collaborate the neuroscientists have to acknowledge that these different levels of inner conflict exist and that they are central to the phenomena of mental illness. Otherwise, what we get (and it is exactly what we are currently getting) won't be a collaboration. It will be a co-optation.

I very much liked what Elaine Zickler said about non-gratification. So much so that I'm going to quote it right now. "On the gratification of psychoanalysis, I would add to what Syd said, that making an interpretation can be more gratifying to the analyst than the analysand; can, in fact, be analogous to the brain of the analyst containing the 'you' of the analysand in the way Anne objects to in the poem. Denying gratification in this sense, then, would be to the point of maintaining the "differ"-ance between the two, so as to allow the words, and subjectivity, of the analysand to emerge." So in that sense non-gratification is really a good thing. It's an anti-cooptation technique.

I would add that the excesses of anonymity that Syd and Susan referred to that have given the technique a bad name generally missed the real utility of the technique. They focused on not gratifying consciously expressed wishes (like "Where are you going on vacation?") and, more importantly, not gratifying what the analyst imagined the unconscious wish might possibly be (which since there's always presumably an unconscious wish hiding behind what a patient says, meant not saying anything at all until you knew what the unconscious wish really was and could make a balanced interpretation about it). But the real action of psychoanalysis comes in the transference and countertransference which involve the "Me" of the patient unconsciously trying to coopt the "Me" of the analyst and the analyst unconsciously "gratifying" this unconsciously co-opting wish by reacting in kind without the "I" of the analyst recognizing it. Effective non-gratification involves the "I" of the analyst feeling the co-opting push or pull on his "Me" -- being conscious of his countertransference impulse -- and instructing his "Me" to remain calm so that he doesn't enact the impulse (enacting means doing the same emotionally charged interpersonal dance that the patient elicits--is driven to elicit--in other important relationships outside analysis, like "I'll be the victim and you be the abuser" or "I'll be the victim and you be the rescuer" or "I'll be the hero and you be the dragon" or "I'll be the top and you be the bottom," "I'll be the smart one and you be the stupid one," "I'll be the skeptic you be the believer." etc. etc.). In other words non-gratification means being reflective rather than reactive about these interpersonal agendas that can be felt in the mutually co-optive emotional interplay of transference and countertransference.

Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern are NOT dead!

Name: Anne Dalke

Date: 2003-10-19 14:57:57

Link to this Comment: 6919 |

Contra Elio, I'm having a very easy time imagining/feeling/knowing that this conversation is a much-needed contribution to and intervention in the current state of mental health care in our culture; at the very least, we are making public and archiving here a conversation about what happens in the analytic situation that can prove very useful to those who have not engaged in that experience. What I see going on is much more than "brave" neuroscientists and psychoanalysts letting one another into their laboratories: rather, the doors of both sorts of labs are being thrown open here for all sorts of amateurs and professionals with interests in mental health to look in/listen in/speak up...

and I have an amusing contribution to make to the discussion. Just about the time, yesterday, that Elio was declaring the death of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (and their replacement, in this post-modern performance, by Prozac), I was taking my children to see Tom Stoppard's Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead at the Arden. This was the first time I'd seen the play; I laughed heartily throughout (as did my kids)...and lay awake for hours afterwards, thinking through its ramifications/contributions to our conversation about mental health...

In hopes of sleeping tonight, I write some of them out here (including some of what I learned from a good lecture on the play I found on-line. What interests me about Stoppard's play, in light of where Elio began our talking (w/ his performance of Hamlet's depression) are three things:

- its portrayal of an absurd world, where the "game" we are playing and the "rules" we are playing by are not scripted;

- its portrayal of the internal (conscious-unconscious) conversation via which we can negotiate that world;

- its portrayal of the interpersonal relationships via which we can likewise.

(Occurs to me that this might be a fine dramatic representation of figure of the three "interacting "loops" Paul handed out @ the panel:

To "play" out this interpretation a bit...

- Stoppard's play is very Beckett-like; my first thought was that it was the theater of the absurd: a portrayal of a world w/out logic, w/out meaning, and w/out anything to help the characters make sense of it. R&G are unsure, anxious, desperate, w/out memory, w/out any way to orient themselves, and they spend most of their time playing games, trying to pass the time, stave off the fears that arise when they are silent. AND YET, if that were all it were, "just" a description of a meaningless world, the play wouldn't be so compelling. I think there are two reasons why it has such resonance (and offers such hope) for me.

- There are all sorts of biographical reasons why critics see all the "unidentical twins" in Stoppard's plays as carrying out a dialogue between two aspects of self: an "intellectually incisive" part and and a slower, more playful part. If, as Paul suggests above, depression might be understood as a "failure of the unconscious to communicate with the conscious," then Shakespeare's representation of Hamlet's dilemma is very nicely replaced, for our purposes, by Stoppard's interchange between R&G, whom we can understand as representing two parts of the brain: Guildenstern is consciousness, agonizing endlessly about meaning; Rosencrantz is the unconscious, the child-like wanderer, not quite understanding the conscious meaning-making, but ever-experimenting w/ new games, new ways of playing....

- Even more encouraging to me, though, is the "interpersonal" reading of their relationship: unlike Beckett's characters, R&G are FRIENDS to one another. Their clear affection for and acceptance of one another counters the absurdity of the situation in which they find themselves.

And it is in this movement from interpersonal to intrapersonal dialogue, the ways in which, in psychoanalysis (in

Elio's striking formulation) delayed (interpersonal) gratification can lead to (both interpersonal and intrapersonal) reflection... that a way emerges to make meaning in an absurd world. In their affectionate engagement with one another, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern put into action what Hamlet has been unable to do alone. Their verbal exchanges are not just clever for the sake of being clever; it is in their imaginative, interactive exuberance that the world gets made, and re-made...

as it is being re-made here.

For which, again, my thanks--

Anne

P.S. For those who (like me) get at these things best through art, two further suggestions: R&G Are Dead is running @ the Arden til Nov. 9; I highly recommend the performance. And: Mark Lord will be staging a performance of Hamlet @ Bryn Mawr, Nov. 14-16 and Nov. 20-22. Mark's work expresses an aesthetic he once described to me as "belated nostalgic modernist"--which I take to mean that his playful deconstruction/dissassembly of classical scripts is a means to reconstruction, to enable us to see them freshly, fully, in all their range of possibility and meaning (his gesture, in other words, is ultimately toward meaning and purpose, a recognition of the absurd that insists on stepping beyond, stepping out....). I recommend this performance as well (based on all his earlier work I've seen/enjoyed/been stretched by) and will ask Mark to post details here...

science, hermeneutics and psychoanalysis

Name: Dorothea L

Date: 2003-10-24 11:20:40

Link to this Comment: 6990 |

First of all my thanks both for the forum and for this opportunity to continue the discussion, which is opening a wealth of interesting questions. My background is psychology (in Munich, at the time a center ofr Gestalt psychology (perception - not clinical application, with interest in bioloby and philosophy, the social work and psychoanalysis with a "hobby" in neuropsychology. Most of my time is spent in clinical practice,working with people with pre-oedipal issues.

I found it fascinating that in the discussion "scientific" and "artistic" understanding started to emerge as focal points. I believe that they reflect cognitive preferences, and that the question of hermeneutics vs. science is releated to them, as well as the question between conscious and unconscious. I will use some analogies to describe my ideas: if we want to paint a picture of something, we can use two basic strategies one would be a line drawing, which is more common. The same picture could also be completed by using shadings, and the "lines" would emerge in the perception of the viewer. In a more scientific analogy, the line drawing ould be more the equivalent of a measure of central tendency, whereas the "ciauroscuro" picture would be more equivalent as an indication of the spread around that central tendency. Gestalt psychology (and now neurobiology) show us how extremely intricate the sampling and other organizing processes are that lead from more basic levels of stimulation to our subjective perception,largely based on statistical filters. With that in mind, I believe that (over-simplified) conscious experience is similar to the "line drawing" or an "executive summary" as a result of the manipulation of the bsic "cloud" of data that comes into our subconscious. The "teleportation" in unconscious processing may allude to this more global quality. Cytowick's studies of synaesthesia are interesting in this context, because they hint at coordinating structures in the limbic system where intra-modal integration takes place and by the same token seems to give rise to some transmodal aesthetic qualities. I don't believe it is an accident that he was also interested in the "art-science" conflict. I also like his work, because it reminds me of neurology in Freud's tradition, with a holistic, systems perspective (as referenced in Kaplan-Solms).

Kaplan-Solms seems to hint that our brain hemispheres are geared for this "dual processing" with the right hemisphere having more impact on procedural learning/memory (which I suspect may be more related to primary process, with art as conscious, abstract expression) and the left hemisphere being more influential in declarative memory, our paradigm of consciousness.

Functionally, suboncscious and conscious could be seen as analogous to vision, with our consciousness being equivalent to our focused vision and the subconscious dealing with the vast amount of information in our peripheral vision (and telling us where to focus).

In my mind, much of the discussion on 10/8 dealt not necessarily with neuro science vs. psychoanalysis but with a mindset which sees systems as linear (the old machine model) vs. complex (and evolving). What we experience in everyday practice with "brain science" is bad science, which sees the brain as much too static, and disregards psychoanalytic evidence for its complexity. In addition, there is a confusion between the brain as a structure and the mind as a process and result of a process. Knowing the structure can tell us some of the limits of what the brain cannot do, but can't predict the mind, because all the possible interactions of the substructures and feedback loops are too many. No one expects biologists to predict the next step of evolution. I think that good neuroscience may acutally help us, by providing "hard data" for the brains plasticity and showing the error of the old, overly static models, and give us new respect for the organizational feats the brain is capable of (as platform for the mind).

Even the question about gratification is related to this issue: the damage of gratification can be explained within a systems perspective - gratification, through satiation, temporarily tends to "close" the system. If you are happy you don't have to think about why. Premature gratification therefore undercuts the psychoanalytic attempt to become aware of the systemic aspects of our experience and learn to integrate them for future increased efficiency.

psychoanalysis, neuroscience, and evolution

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2003-11-02 12:28:46

Link to this Comment: 7077 |

I confess freely to the "ultimate agenda" of having this forum "

evolve into a discussion ... of how psychoanalysis and neuroscience can work together to improve the mental health care system". Along which lines a couple of thoughts, based on the preceding, and some other post-panel exchanges.

The issue of what we MEAN by the conscious and the unconscious continues to seem to me a fruitful area of exchange, not in order to be able to say "I'll be the smart one and you be the stupid one" but rather because there's clearly a potentially fruitful lack of gratification around this issue (assuming we are willing to postpone gratification), and so it is a place where our differing stories (conceptual frameworks) each have the potential to be productively altered by the others.

Dorothea has added the useful (to me at least) thought that the conscious and the unconscious differ not only in the degree to which "we" are aware of what is going on but also in the STYLE of what is going on. I think some more exploration of the differences in style between the two would be helpful in better understanding (and productively dealing with) not only the conscious and the unconscious but also the nature of communication between them (if the styles are different then they have an interesting communication problem/challenge). Several of us have written a paper on "interdisciplinarity" that characterizes the style difference as "metaphoric" vs "metonymic", a distinction with interesting similarities to Dorothea's "central tendency" vs "spread", and suggests some ways that these differing styles can productively intersect. While this is one difference between the two systems, its not the only one. There's an old list of some other differences at Exploring the Consciousness Problem.

What's not on that list is what I suspect is another important difference between the conscious and the unconscious systems that has been in the back of my mind for some time, for both neurobiological reasons and because of "clinical observations" (both of myself and of others). It was crystallized by an email from Thomas Bartlett, assisting with my needed Lacan education. According to Tom, Lacan makes a major point of "negative hallucinations" and the "falsifying ego". A hypnotized subject told there is a table in an empty room, for example, will, when brought out of hypnosis, walk AROUND the (absent) table, and will, when asked, provide various explanations (other than the existence of the table) for doing so. The point is that it is the business of the conscious (the ego in Lacanian/Freudian terms, if I understand correctly) to "account for" or "bring coherence" to one's behavior and one can, in some situations, observe the "falsifications" it uses to achieve this (for me, the point is equally well made with the blindspot or ambiguous figures).

What I suspect is quite different about not only the "style" but also the underlying organization of the unconscious is that "coherence" is of very much less significance to it than to the conscious. The unconscious, as I understand it, is a series of semi-independent modules each of which has its own information and objectives. The unconscious is organized in such a way as to adjudicate more or less effectively among the expressions in behavior of its components but not organized in such a way as to give any priority (or even meaning) to being "coherent". To put it differently, the unconscious is fragmented, rather than unitary, and organized in such a way that there is nothing at all amiss if behavior indicates a belief in Santa Claus at one point in time and a disbelief in Santa Claus at another. "Fragmentation", and one's fear of it (if one experiences such fears) are a concern of the conscious. They are, quite to the contrary, the essence of the unconscious.

Does this have clinical implications? I think so. Among other things, what it suggests is that "inner conflict" may occur between the conscious and the unconscious but may equally occur between various of the semi-independent components of the unconscious. We all know the phenomenon of people knowing quite clearly at a conscious level what is bothering them but not being "helped" by so knowing, so maybe we need to work not only on making things conscious (ie being sure the conscious and the unconscious are not in conflict) but also on helping to resolve conflicts between different parts of the unconscious (a matter for which making things conscious may or may not be helpful)?

It strikes me that there are interesting broader implications of the coherent/incoherent distinction as well. Maybe "gratification" for the conscious consists in coherence, and so may oppose/inhibit other kinds of gratification? And perhaps if we get too caught up in being coherent it also inhibits our ability to hear the stories of others and allow our own to be modified by them? I'm enjoying/learning from this particular less than coherent forum, hope others are as well, and that we can/will continue the rich"complex (and evolving)" process we've started here.

tolerance for conflict

Name: Anneliese

Date: 2003-11-02 21:14:39

Link to this Comment: 7081 |

Paul, I'm a little confused--you say first that the unconscious comfortably holds two (or more) 'conflicting' notions at once; but then you suggest that such differences at the unconscious level may be distressing. What am I missing?

unconscious conflict

Name: Paul Grobstein

Date: 2003-11-03 08:05:25

Link to this Comment: 7085 |

Anneliese, I don't think you're "missing" anything. I think you've identified a problem with what I said. An interesting one. Maybe even a VERY interesting one.

You're right. The notion that the unconscious can without conflict act so as to express a belief in Santa Claus and not express such a belief means that something else has to be going on to create troublesome "internal conflict" of the class II (within the unconscious) type.

Betcha a million dollars that the "something else" that is going on involves consciousness, ie what creates trouble/discomfort is not actually a conflict within the unconscious (at least not usually; I can imagine such a thing but it would manifest entirely differently) but rather that the conscious is getting conflicting signals from the different areas of the unconscious and not knowing how to adjudicate between them.

This remains different from the conscious/unconscious conflict but, you're right, it isn't accurate to describe it as simply "between ... components of the unconscious". THEY don't notice or care about it; only consciousness does. So we could (1) remove consciousness or (2) help it adjudicate the conflict or (3) try and alter one or more of the conflicting components of the unconscious.

I suspect most people wouldn't favor (1) and might be most comfortable with (2). But ... what about (3)? It seems to me in many ways the most appropriate, if perhaps the riskiest/most challenging?

global? fragmented?

Name: Sharon Burgmayer

Date: 2003-11-03 08:55:06

Link to this Comment: 7088 |

Paul, I like your

prompt to consider the different styles of the conscius and unconscious, especially insofar as that difference is what causes communication problems between them and within us. Identifying an inherent drive within the conscious to find and/or make coherence works for me. However, at first pass, I am having difficulty integrating your description of the unconscious as "fragmented" and compartmentalized with

Dorothea's description of the "global" "cloud" of information. While I will continue to chew on that, I wonder if you have a suggestion for what the the unconscious

does value? What is the analog to the drive for coherence in the conscious that accounts for the connections made by the unconscious?

what does the unconscious value?

Name: Anne Dalke

Date: 2003-11-04 16:42:39

Link to this Comment: 7113 |

...mulling over Sharon's good questions about what the unconscious values? what accounts for the connections it makes?...i find myself thinking (in response to the first question) that "value" is a concept of the conscious mind and (in response to the second) that unconscious connections are not rational or logical, but associative, random, contiguous, "neighborly." i and friends once wrote about these different qualities (we called them "metonymic") but i'd love to hear more about this from practitioners, those of you who listen all day to/try to evoke in your patients the landscape of the unconscious: what does it "value"? what accounts for the connections it makes? (and how do you--do you?--go about altering them?)

conscious-unconscious and fragmentation

Name: Dorothea L

Date: 2003-11-05 11:19:26

Link to this Comment: 7121 |

First of all, I love this discussion and I don't know of any other place where I could have it.