Main Line Unitarian Church

July 24, 2005

"The Grace of Revision"--

Making Community in Public

Anne Dalke

July 24, 2005

"The Grace of Revision"--

Making Community in Public

Anne Dalke

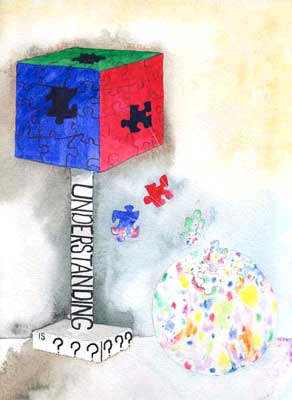

This and all other images from the Watercolors of Sharon Burgmayer

(The tune is on p. 210 of your hymnal; the words aren't....!)

Wade in the water, children,

Wade in the water,

God's a-gonna trouble the water.

Well out of the mountain come fire an' smoke

God's a-gonna trouble the water

Jehovah nobody be he could've spoke

God's a-gonna trouble the water.

Wade in the water,

Wade in the water, children,

Wade in the water,

God's a-gonna trouble the water.

Well, I'm walkin' down the highway an' the water's gettin' low

God's a-gonna trouble the water.

Walkin' down the highway, nowhere to go,

God's a-gonna trouble the water.

But it's wade in the water,

Wade in the water, children,

Wade in the water,

God's a-gonna trouble the water,

God's a-gonna trouble the water,

God's a-gonna trouble the water.

Why would you want to do that?

I'm inviting you to walk with me into some troubled waters....

What do you see,

Why would you want to wade in troubled waters?

Why would you want to invite the children to?

Why would you (want to?) sing about their doing that,

early on a summer Sunday morning?

when you look @ this painting?

Sharon Burgmayer's commentary focuses on the symbolism of the "brokenness" of a thing serving to support another....: the broken iris flower supports a frog, the broken branch supports the turtles, another broken tree branch supports the human...with a decidedly dejected, sad, broken spirit..... The painting, she explains, alludes to John 5:1-4 ("an angel went down...into the pool, and troubled the water: whoesoever then first after the troubling of the water stepped in was made whole of whatsoever disease he had...."). Thornton Wilder uses this idea in his play, The Angel that Troubled the Waters, where a physician, disappointed at coming late to the pool, is asked, "Without your wound where would your power be?" Sharon painted this physician, in "The Pool at Bethesda."

According to Rick Hamilton, a colleague in Greek, "troubled" is tarasseto, a common word for stirring up, muddying. Classical uses= stir up the sea or earth, agitate the mind, throw an army into disorder, cause bowels to relax (!), stir up political disorder. Passive forms in the New Testament mean "be troubled, agitated, frightened, intimidated."

to hear others' glosses on the painting and the terms behind it?

To hear the artist's explanation of where it came from,

and what she was doing with the image?

To hear the etymology of the words which first stirred her?

Did learning these things make any difference

in your experience of the painting?

Anyone want to re-paint it differently?

Let's experiment with another one....

What do you see,

when you look @ this painting?

From Sharon's 9/11 video describing Understanding's Birth:

I was walking along the deserted beach.

But as she also said to students a few years ago, on the course on-line forum: You... have told subsequent stories that have multiplied the dimensions of "understanding" that can be

extracted from it. From these stories I, too, now appreciate the ambiguity of pieces moving in both directions. How you see it depends where you are. (Not unlike life.)

The quote hung in my mind:

"Understanding is the booby prize."

Out my mind's fog appeared

a sphere.

I felt it was Life, the experience of Life.

Vibrant, colors changing, shifting and mixing unpredictably.

The creation of the spirit.

Adjacent to the sphere, a cube emerged.

The sides of the cube became colored

red, blue and green--

the primary colors of vision--

and I could more clearly see how

the cube was formed from fitted puzzle pieces.

I recognized the cube as rational thought.

Then pieces of the puzzle-sided cube

fell away, became mottled and fused

to become part of the sphere.

As the pieces fit into the cube,

intensely bright white light peeked through the cracks.

I understood this as the message:

the structure of reason had to be dissassembled,

the artificial distinctions blurred,

to experience Spirit and know the full beauty of life.

And so I created the painting,

elevating the cube on a pedestal

that spoke of the cube's demise.

Understanding born solely of reason is not enough.

The Spirit of Life is beyond all reason.

listened in on a prior conversation--

what do you now see in the picture?

Any one want to re-paint the picture?

What just happened here?

I frequently use Sharon's paintings in my classes as a source of experiences that are more direct and less mediated than those provided by texts. Students have immediate responses to images: they find themselves more easily able to "read"them--a reading that the rest of the class (and the artist herself) can complicate and build on.

There is a theology behind this practice

Each of us

At a place like Bryn Mawr, which prides itself on offering a rigorous education, students are hesitant to speak out in class, afraid that they will "get it wrong" and so be publicly corrected...

I've gotten a wonderful range of student "witnesses" to this interactive process. They speak of my

Not to say there aren't also concerns, in particular a fear of the potentially negative outcomes of public conversation/democratic process

From a student who withdrew from a new course on "Beauty": How you all manage to discuss those intimate beliefs, dreams, experiences every week in class and on a public forum makes me want to cringe. i do admire you all for doing it though, to me it seems as though you're willing to put yourself out there on the line every day. that takes guts and a belief in the goodwill of humanity and life which i am more cautious about.

I actually don't think I begin either with a presumption of goodwill--

the more we all can grow and learn.

This implies

which seems to me quite congruent with my

Quaker understanding of the rich resources of Spirit.My friend Kaye Edwards, a Quaker and developmental biologist who teaches at Haverford, says, this is about being open

to the unconscious, to the spirit, being willing

to take risks, not to be mired in dogma and

concretized ways of thinking and teaching and

learning.

=need for assurance that "all will be well" in the end?

=need for (Quaker?) belief in "that of God in everyone"?

or of any particular level of education. Just that the more people willing

to talk frankly and freely with one another, about how they experience the world...

(drawn from their own life experiences) to contribute to these conversations,

is a song about exploration of a particular kind--

which leads to the making of a community of a particular kind:

one that is open, porous, labile, willing to be tested,

willing to test, in conversation, any and all presumptions,

refusing ever to stop or "close" the conversation

around any agreed-upon position--

including any litmus test of what constitutes "community."

Such a song has three keynotes:

|

the original relation each of us has (can have!) with ourselves/our unconscious/Spirit as a rich reservoir for knowing |

|

|

the original relation each of us has (can have) with other knowing (and unknowing!) selves |

|

the original relation each of us has (can have) with the universe. |

|

Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion of revelation to us, and not to the history of theirs?(Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Nature")

This seems quite akin to what I learned--with thanks to Danica Doroski--from Charles White McGehee, "Our Beliefs," in "A Pocket Catechism for Unitarian Universalists: We believe that the individual is responsible for personal actions and to a great extent, for individual destiny. There is no outside supernatural force to intervene. We must search constantly for wider truths and application of moral principles. Our religion is influenced by expanding truths.

It is also expressive of a key Quaker concept: Margaret Fell reports on a debate with clerics who were citing Biblical passages to support their claims, to which George Fox retorted, 'You will say, Christ saith this, and the apostles say this; but what canst thou say?' Fell continues, 'This opened me so that it cut me to the heart, and I saw clearly we were all wrong. So I sat me down in my pew again, and cried bitterly. And I cried in my spirit to the Lord, "We are all thieves, we are all thieves, we have taken the Scriptures in words and know nothing of them in ourselves."' (Mary Garmen, et. al. eds. Hidden in Plain Sight: Quaker Women's Writings 1656-1700. Reported by Steve Smith in "The Spiritual Roots of Quaker Pedagogy," Minding the Light: Essays in Friendly Pedagogy)

The trick here is BOTH to claim what we know experientially--

AND to do so with a willingness to revise, and be revised,

by our encounters with others.

AND to do so with a willingness to revise, and be revised,

by our encounters with others.

A student whose parents are both Methodist ministers described the process this way:

...A professor, whom I admire and respect and whom I

want to admire and respect me, said in response

to my paralyzed fear of rejection as I approached

the project of writing...."You will never get it

right, but if you accept that and continue

anyway, then you can always revise your ideas,

come back to them later if you want. If you don't

write, you can't revise." I was struck by the way

this echoes, in a loose paraphrase, the way I

think about the notion of grace in relation to

faith. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism,

rejected "works' righteousness," arguing that the

grace of God is not given to human beings because

of the things that they accomplish or the

goodness of their character. He said, instead,

that humans must accept that there is nothing

that we can do to earn God's forgiving grace

because we'll never be able to deserve such a

gift through our own works, but that God gives it

anyway and all we must do is then accept it. In

so doing, we allow for the possibility of true

transformation.

In my faith life and my academic life, I hear

strains of the same things. My work will never be

perfect. There will always be something desirable

missing, but in accepting that, I accept God's

loving power in my life and my own power over my

work, each striving to create something new out

of the fragments that exist, each hoping for a

moment or two of transformation. That's grace.

That's revision. For the first time in a long

time, I feel that the two halves of my life are

not so distant from one another. The private

familial world of my faith constantly informs my

work and the public world of my academic life

works on my faith. In revision, I find grace

within the academy, and in grace, I find a chance

to re-envision the self, myself. (Rachel Wright,"Meditations on the Non-Existent 'I' in Text")

I encourage my students to conduct this revision in public, on the web. A primary location for this work is the Bryn Mawr College website Serendip, which explores the pleasures and productivity of uncertainty, by facilitating connections among ever-expanding numbers of contributors.

...serendipity is a big part of our lives, but it grows in direct proportion to sociability." (Elizabeth Bumiller, "If They Gave Nobels for Networking...." The New York Times Week in Review. June 5, 2005. 4A.)

In a traditional society, if we ask a man to name his best friends and then ask each of these in turn to name their best friends, they will all name each other so that they form a closed group. A village is made up of a number of separate closed groups of this kind.

But today's social structure is utterly different. If we ask a man to name his friends and then ask them in turn to name their friends, they will all name different people, very likely unknown to the first person; these people would again name others, and so on outwards. There are virtually no closed groups of people in modern society. The reality of today's social structure is thick with overlap - the systems of friends and acquaintances form a semilattice, not a tree. (From Christopher Alexander, "A City is Not a Tree")

Web forums are experiments in whether (open? fragile? egalitarian? democratic?) communities CAN be formed among people who begin less with a shared set of common beliefs (including any a non-negotiable sense of what constitutes community) than with a shared desire to learn, to go exploring.

It is our task, as educators and citizens of the world, to work with our students to help them and ourselves develop the skills needed to continually create and recreate a human story from which no one feels estranged. (11 September 2001: Thoughts and Forum Archive)

The web is such a profound resource for

contemporary education because of its

Some details:

A couple more notes thrown in for "good measure":

The wider significance of our classroom work:

So: what canst thou say?