Questions, Intuitions, Revisions:

Telling and Re-Telling Stories About Ourselves in the World

A College Seminar Course at Bryn Mawr College

| Questions, Intuitions, Revisions: |

In his Preface to The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, Michel Foucault reveals a primary concern in his investigation: "observing how a culture experiences the propinquity of things, how it establishes the tabula of their relationships and the order by which they must be considered" (xxiv). In other words, he strives to create order in a disparate universe: to characterize, to categorize, to define, to differentiate - namely, to arrive at some semi-satisfactory state of understanding that accounts for the vast inconsistencies that populate the world. Does this sound familiar? Of course: it reflects the end toward which humanity has been striving since the origin of thought. Do we not inherently realize, as Foucault puts it, that "a 'system of elements' - a definition of the segments by which the resemblance and differences can be shown, the types of variation by which those segments can be affected, and, lastly, the threshold above which there is a difference and below which there is a similitude - is indispensable for the establishment of even the simplest form of order" (xx) and consequently wish to act upon this idea? We do, a fact evident in our explanation of the biological hierarchy of life; in the construction of countries, states, towns and other non-natural borders; even in the divisions in our schools as to graduating year, academic field, extracurricular interests, and the like. But Foucault's purpose is not nearly so simple. He sees a spectrum of knowledge ranging from this "system of elements" or "fundamental codes of a culture" at one extreme to the "scientific theories or the philosophical interpretations which explain why order exists in general, what universal law it obeys, what principle can account for it, and why this particular order has been established and not some other" (xx) at the other. Between these extremes, he finds "the pure experience of order and of its modes of being" (xxi), the springboard for his ensuing "archaeology." In sum, he believes that he has found a fresh approach in humankind's epistemology and so wants to re-tell "the order of things" in relation to this new inspiration.

Is this any different from our own motivation for re-telling stories? Not really. When our experiences yield new epiphanies or when enhanced knowledge affords new perspective on our world, we feel compelled to share this learning with our compatriots in an attempt to make life's mysteries more comprehensible for ourselves and for those who share in humanity's struggle for truth - in essence, we yearn to re-tell the story in light of our personal findings. When we are captivated by a novel, a newspaper article, a bit of gossip, do we harbor it silently or do we tell a friend, a classmates, a teacher, or a family member? Most of us tend toward the latter. Why? Quite simply, the story has re-shaped our outlook. It has caused us to ponder and reevaluate our own conception of the world, and thus, in imparting it to others - in "re-telling" it - we can better understand our perception of this knowledge in addition to enriching the perception of our listener.

If humankind is so eager to relate its experiences and to analyze them and propose questions in its eternal search for greater knowledge, why, then, is storytelling such a specialized field? Should we not all be writers, poets, storytellers, pondering intellectuals? In an informal sense we are, but naturally, there must be some inhibitions preventing us all from entering this field. Some may feel they are not equal to the task, perhaps deficient in the communicative gifts of the effective storyteller; others may fear persecution or discord stemming from their unique interpretation; still others may prefer to listen, ponder, and muse rather than question, assert, and propose.

What do we hope to gain by exercising or deferring our capacity to re-tell stories? Edwin A. Abbott, like Foucault, had a story to re-tell, yet his - Flatland - takes a starkly different form. Why? More specifically, what did Abbott hope to gain in telling his story as a satire? What losses, what costs, did he wish to minimize? Taking into the consideration the social climate of the time, it is possible that a straightforward, academic piece may have invited rampant disapproval. Thus Abbott, undoubtedly feeling that his social criticism merited expression despite the possible cost in a dissatisfied audience, chose to submerge his message in the experiences of A. Square. He can still express his "hope that these memories...may find their way to the minds of humanity in Some Dimension, and may stir up a race of rebels who shall refuse to be confined to limited Dimensionality" (82) - in other words, his desire that future generations in his own world not be so insular - but without jeopardizing himself. In the same way, humanity weighs the costs and benefits of re-defining its world through stories that enlighten and attract readers without compromising their message.

Why are we motivated and reluctant to re-tell stories?

How does it profit us and what are the costs?

As humans we have been telling, and re-telling stories for ages. At first storytelling, or oral tradition was a way of keeping history and knowledge alive. At this point we were motivated to tell stories as a way of survival, as a method of immortalizing the lessons we learned during our first days of existence. Through out those seemingly innocuous stories, vital life lessons were taught. Without them would the human race have survived? Later the ancient civilizations told myths, legends, and fairy tales to explain the unexplained. Through those tales we gain our first stories, and in-turn the first marked evidence of an organized civilization. Subsequently philosophers would use stories as a tool to teach, and moralize to the masses. Even now we tell fairy tales to children in hopes to appease, and impinge upon them some sense of good and evil.

Modern day writers are motivated by opinions, newfound knowledge, and experiences to tell us stories. Today writing, an evolved form of story telling, is a tool of mass media. Authors can publicize their ideas, and theories. One of the most crucial and hazardous tools in history has been a story or opinion written in a book. Take for example the Federalist X. The American and French Revolutions would not have occurred, if its ideals had not inspired nations to revolt! History its self is the greatest re-told story of all time. History is in the hands of its authors. A perfect example is the textbooks that we use in school. For example if you compare the history books of a child in the United States to that of a German child you will get two radically different versions of the events of World War II.

This brings me to one of the flaws in telling and re-telling stories. Each time that we re-tell a story, we change a small part of it to fit our perception of how it should have been (according to us). Take for example how many different versions of Cinderella we have heard!! If that’s not enough look at everyday life occurrences. Take gossip for example. One minute you hear “someone fell down the stairs.” The next “some one was pushed down the stairs, got concussion, broke 5 ribs, and was hauled away as a bloody lump in an ambulance. Only after having been pulled back from the brink of death by EMS.” Personally this shining example of human nature would quench any burgeoning need I had to tell a story. The risk of it being maligned and perverted for the general public’s entertainment makes me cringe.

In the beginning stages of societal development the telling and re-telling of a story could have been the difference between life and death. Later on, books such as Flatland and Federalist X were used to propagate important issues such as Women’s Rights, Civil Rights, and Educational Reform. Even today’s our news papers re-tell events to the masses. In total as a society, and a race humans have profited endlessly from the telling and re-telling of stories. We have used the re-telling of stories as a survival tool, a method of education, an implement of morality, a battle cry, and more recently as a tool of mass media, and a device of advertisers. But with the good comes the bad. Each time a story is retold its original structure is subtly altered, and what is lost can never be replaced. Also with each re-telling a story will have a different meaning cast on it. What was originally a fairy- tale in the 15th century, could turn into a politically loaded metaphor of the 21st century.

In conclusion stories will always be told and re-told until the end of time. A story is the true fountain of youth. Cinderella is immortal, as is Briar Rose. Prince Charming will always be the standard that women ruthlessly hold men up to. Once in a story you will be forever young. But with endless youth comes the high price of time. A heroine and role model today, is a feminist’s arch foe tomorrow. But remember a villain is always a villain. Woe to those who go down in history as the stepmothers, and evil Queens!!

Why are we both motivated and reluctant to retell stories? What provokes us and what prevents us? How does it profit us and what are its costs?

At the beginning of language, humans used stories as a way to explain history. Before there was writing, there was spoken history that passed from village to village and father to son. The stories dealt with origins of the world and famous battles that took place. The motivations for these stories is quite obvious because curiosity is a big part of human nature. However, in today’s society, stories have become more complex and the telling of them has consequences with the joys.

Parents usually start reading their children familiar stories such as fairy tales that are fun to tell. There is much motivation to tell fun stories because the audience reacts positively, whether through laughter or a simple smile. However, with society changing, some parents feel reluctant to tell traditional fairy tales. As we have discussed in class, fairy tales often show women as weak characters that need princes. They also can be gruesome, which could cause nightmares. All in all, though, it is usually enjoyable to tell children’s stories.

However, there are stories that are not easy to tell. Many of these stories deal with religion in some way. In ancient society all people worshiped the same god, but as time progressed, so did beliefs. Many Jews were persecuted for telling their stories about their god. If they had not spoken their beliefs, though, their children would not have learned how to worship. Other religions faced the same problems. They had to decide between speaking their beliefs and serving their god, or keeping silent and being disobedient.

In Flatland the square must decide whether or not to speak about his mathematical discoveries. Many early scientists faced this same dilemma. Magellan said, “The church tells me that the earth is flat but I have seen the shadow on the moon and I believe in the shadow more.” Science could have advanced much faster if early discoverers were not forced to recant their beliefs. Each scientist had to decide whether to keep silent and avoid trouble or give society the chance to advance. In today’s society there is not so much persecution because of science. Even so, anyone who discovers something new must decide whether or not to put forward the theory. If it is correct, he or she will be rewarded, but if the theory is incorrect, other scientists might reject the data and the scientist along with it.

There is a benefit to telling stories because when one believes that something is true, or worth knowing (as is the case with fairy tales), then there is an inner compulsion to share that knowledge. In a perfect society, all stories would be heard without judgment of the story teller, but just like what happened in Flatland, there are sometimes repressive consequences for telling an unpopular story.

We are reluctant to tell our stories for some of the same reasons we are motivated to express them.

Our need/desire to "fit in" corresponds to both our motivation and reluctance. On the one hand, we'll tell a story to establish our sense of belonging, yet we may resist telling the same story because we worry that it will illustrate just the opposite -- that we don't "fit in."

Insecurities and/or feelings of inferiority are reasons we sometimes hold back from telling stories -- we worry what others may think of us once we reveal ourselves. We're taking a chance when we express ourselves because there is always the potential for discomfort if, for instance, the dialogue pushes us into revealing more than we had originally planned.

Sharing ideas about who we are and where we come from allows others to know something about us, and the ensuing exchange can be exciting. In social situations, we tell our stories because we hope for a reciprocal relationship/friendship. It's a wonderful human experience to connect with someone and begin a new friendship. Yet, having stated that, I'm sure most of us have experienced other facets of this situation. How often have we prematurely judged someone we've just met, based solely on a story they've shared?

If we read Flatland, and never read other works by Edwin A. Abbott, it gives us only one reference (albeit a solid one) as to who the author was, where he comes from, etc. But reading the man's biography as well as other works helps us to form a more complete picture of the author.

We use stories as a means of communicating and opening oneself up to suggestions,possibilities and others' interpretations. We use stories as a way to seek opinions and/or advice and counsel, as well as to educate -- but there are limitations. Time (or space in say, a newspaper column) often dictates or prohibits the full telling of a story. The author risks the reader forming opinions based only on what time/space have allowed her to write, and so she must be meticulous in choosing which points she wishes to exaggerate and/or leave out.

As to why we change stories, I believe we revise and rewrite our stories to make them more accessible to readers/listeners. We're always trying to better define the story, or better illustrate a point which aids us in the process of convincing the reader of our truths.

Meg Devereux

I am having the worst time condensing what seems to me the subject of an entire semester, the content of a long magazine article, or the ongoing topic of an all night bull session. The need to change or retell the stories we tell about the nature of the world.

As a reading addict for the last forty years, I could start with the big story that begins, “ And an angel of the lord appeared to Mary…” This pretty much tops the fairy tales for me for sheer magic, beauty, plot and promise. I could stagger through hundreds of other retold tales including those of Austin, George Eliot, Forster, Woolf, Waugh, Huxley, James, Wharton, Fitzgerald, and the far less known but appealingly direct Bawden, Gilchrist, Sheilds, and a host of others who deal with the isolation of class stratification and the search for connection to self, others and the Other, their own definition of a transcendent truth. If I start with the annunciation, I would probably end the list with “…world without end. Amen”.

What then motivates the creators of these richly woven diverse strands, strands that become the whole cloth of retold stories? I believe it is the desire to give meaning to their lives and the lives of their readers in a fresh, revelatory, even jolting manner.

When Edwin Abbott wrote Flatland, I think he was combining the central story of his vocation with the spiritual and social needs of Victorian England. The story of Jesus who revolutionized the old order of law, retribution and rigid class stratification with the radical message of love, forgiveness and equality in the eyes of God was a story ripe for retelling in a manner that might alert a pious Victorian society to its own complacent acceptance of the implications of its class system. Abbott’s sometimes overly enthusiastic message only underlines his intense motivation. His mathematical gifts and abilities also might have fuelled his motivation as Victorian society’s rational approach and increasing interest in science and mechanized industry were certainly known to him. He may have seen a temptation to rationalize the needs of humanity right out of sight.

Abbott was possibly provoked into the writing of his tale by the extremes affluence of his educated peers and the poverty of England’s underclass, which supported it. Reportedly this reality was complacently accepted by nearly all the participants, at least those whose voices were most heard.

Abbot’s Flatlanders live in an atmosphere that lacks light or shadow. (1) The narrator begins by rationally explaining the class system of Flatland, (2) and goes on to detail the methods of controlling the lower classes, (3) and the suppression of women and their gifts. (4) He then takes us on a tour of the subtler distinctions among the upper classes (5) and elaborates on the “barbarism”(6) any crack in the complex system would cause. “Mercy” is demonstrated by euthanizing those whose character or shape is a threat to society’s expectations. (7) When the narrator is ultimately shown an alternative and revolutionary three-dimensional world, he is given a whole new perspective and vision of reality. He achieves knowledge of himself; others and the Other, in this case the idea of unlimited worlds. He is open to the gift but is not an active seeker in the pursuit of this new world. It is grace of a sort. Before this ultimate revelation, the narrator shares a story that foreshadowed his discovery of three dimensions. Chromatistes, an upper class mutation of the sort usually stamped out, (8) discovers colour and is made easily visible in a new and explicit way. The introduction of colour to Flatland brings liberation and the joy of creation is spread throughout the land. (9) Art in the form of colour changes the Flatlanders’ perceptions and helps them to see what was formerly invisible. Those in authority see the burgeoning art as “immoral, licentious, anarchical, unscientific…yet aesthetic…the glorious childhood of art”. This creative burst gives, “a richer larger world of thought…the finest poetry…rhythm”. (10) As the influence of art spreads through the classes it soon becomes seen as a threat to the established order of the land. Even women and priests are influenced. (11) Eventually the arts are suppressed by those whose power is threatened. The Flatlanders are returned to one dimension. All accounts of this period are effectively written out of the history of the land. In this land no stories can be told or retold. Too threatening to the stability.

We are prevented from retelling stories when we fear facing a new truth or a new bit of truth in ourselves, in our perceptions of others or in the Other, our vision of what makes the universe’s energy. When we are clinging to a perceived security it is difficult for us to change or retell a story that might push us from that precious niche.

What profits us from stories being retold is being gently lead, dragged kicking and protesting, or shot violently into new visions of our worlds. Sometimes in fairy tales or parables the vision heals. Sometimes in satire and tragedy it turns us around to face places we’d rather not go. Sometimes in poetry or mysticism it sends us into deep places of transformation and we have no choice but to become co-creators in that place of crisis and transformation. Abbott transformed the story of his beliefs into a story that retold those beliefs in a way that spoke to his need to preach change for his world a world of Victorians stranded in a class hierarchy who had become adept at rationalizing the need to support such a stable and apparently unchanging structure.

The cost of telling the changed story is one of giving up old certainties and living in the wisdom of insecurity as both the narrator and, no doubt, Abbott himself were aware.

To me the point of retelling stories is to state and learn a truth or a new truth in a way that makes it apparent, as it wasn’t before. If one other person gains understanding of even a small part of that truth then the story is worth telling, retelling, or changing.

1.Abbott, Edwin. Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. 1885;rpt. New York: New American Library, 1984, p.4.

2.Ibid.,p.7.

3.Ibid.,p.9.

4.Ibid.,p.13.

5.Ibid.,p.21.

6.Ibid.,p.22.

7.Ibid.,p.21.

8.Ibid.,p.22.

9.Ibid.,p.26.

10.Ibid.,p27.

Flatland was flat. There was no denying that. It was flat and boring. The shapes were squares, parallelograms, triangles, circles and even lines. Every shape was easily organized according to it’s sides. What if a shape was born with sides that were different from that of it’s peers? No. This would not be tolerated. The shapes moved from their homes to their jobs to their schools everyday in the same way following the same lines. They moved north and south, east and west. What if someone decided to go in a different direction? No. This would not be tolerated. The shapes intelligence and social ranking was determined by the number of sides it had. What if a shape wanted to go beyond it’s social ranking? No. This would not be tolerated. Flatland was going to be flat and boring. That was that. There was no variety in sides, no up and down and no social mobility. None of this could exist until it was heard. The story needed to be told.

Just like people, shapes can be stubborn. Everyday the shapes went through a routine. The routine made them feel stable and safe. Nothing changed so nothing could go wrong. They were prepared for everything. The square was one of the shapes to try and change this two dimensional world. He wanted everyone to hear and see the beauty that he had seen. Now that he had this knowledge, he felt compelled to share it. But there was still the fear of his peers reactions. It was as much a struggle for square to tell his story as it would be for Flatland to understand it. He were telling stories of a third dimension. Something that could not be seen by everyone but had to be believed. This would not be tolerated. The Flatland society was so frightened of thoughts that might change what had always been accepted that they decided they would get rid of these thoughts. The story teller and his story would disappear

The shapes who told of new worlds faced scorn by their peers just as people with new ideas from our three dimensional history did. These people had their own sphere that showed them something that no one else could see. They retold their story and faced the consequences for their controversial views.

The resistance of re-telling stories may come from the concern of it becoming a re-conception of the original. We risk losing the story’s true meaning. In our college seminar class, for instance, we were assigned to write our life of learning story. In the telling and re-telling of this story, I admit resistance in some areas. I claimed ownership of my original story and the re-telling of it, I felt, would risk it being dissected. I didn’t want it to change in my mind because it was too intricate complicated and sensitive.

What are the costs?

The costs are that the story may become corrupted in the re-telling process. Re-telling has its value, but has a price. We may never feel same way about the story. It will never be the same. We need to be ready to let go of the old story, and be open/accepting of the new one being told. The telling and re-telling made me see another view. As in Flatland I am becoming more aware of another dimension of possibilities.

In his preface, Foucault relates how Borges disrupts a world ordered by categories of "same and other" corresponding to the European arrangement of the natural world into the taxonomies of Linnaeus. In Borges disruption, Foucault discovers an "impossibility of thinking" (xv) relevant to his own consideration of how we come to arrange our thoughts, our knowledge, according to one particular framework. Abbott's Flatland is also of interest in this regard when related to what Foucault calls the "positive unconscious of knowledge" (xi) of a particular era. In the introduction to Flatland, Banesh Hoffmann tells us that in the days when Flatland was written, the mathematicians "were imagining spaces of any number of dimensions. The physicists too, in their theorizing, were working with hypothetical graph-spaces of arbitrary dimensionality. But these were matters of abstract theory" (iii). Abbott's book presents a view of the world according to the laws of geometry, but then challenges this with imaginings of other dimensions. In this way, Flatland makes a different view of the world available to us without any need to await scientific proofs (an advantage fictional stories have over scientific stories).

However, any re-telling and re-ordering of our world has its risks. In Flatland, Abbott addresses the danger when Square is jailed for his attempts to re-tell the story of Flatland's place in the dimensional universe. His fate, it appears, is the fate of a Galileo. But Abbott is a clergyman, and he uses some of the language of religion in describing Square's fate: "Death or imprisonment awaits the Apostle of the Gospel of Three Dimensions" (67). So, perhaps, Square's fate is that of the Apostle. What these two interpretations have in common, however, is that when a different story of our world is constructed it is heard as a threat to the established order. In our Western history, this resulted in a confrontation between the tellers of religious tales and the tellers of scientific tales. Remnants of this confrontation over the ordering of our world persist, as we shall see, in the story telling of "Creationism."

The Uni-tale Universe

(Draft A)

I can only tell you this once:

I am a monk living in self-imposed exile from multiple-story life. My youth was wasted on attempts to duplicate ten-thousand versions of the story of a girl. I came of age in the information age, the natural successor of the duplication age. With so much information, anyone could be anything, virtually at least. Even the poor could step inside a duplicated dream. They were everywhere, instantaneously, these physical streams of someone’s dreams, and being so ubiquitous, they were bound to collide. Collide, combine, combust, fragment, disperse; the cycle of self-propagating thought pieces was hard to reverse. Inside the space of two decades our inquisition changed from breathing in the smell of paper and ink, to attaching some electric apparatus to our brains. The storybook that once fascinated the child was replaced by a game that you could go inside.

Looking back now I wonder at how we gorged ourselves on a combination of fiction and fact until we ourselves became hybrids, part real, part imaginary, unable to tell anymore which was which. The question was asked: could a murderous act be provoked by a song, a video game, or a movie? Soon followed the question of whether or not a fictional image of a crime could indict an innocent person. We spliced reality with fantasy and vice versa until the distinction was nearly extinct. Even songs were assembled bits and pieces; the real version lost in a glass recording room window. Science and science fiction seemed inevitable collaborators in the public perception of reality. Some people wondered if perhaps even a world war could be started by the devious transmission of a false tale in which one world power is being attacked by another.

Somehow my reluctant brain adapted to the oxymoronic idea of virtual reality, and apparently so did many others. I thought maybe it would pass, but then I perceived that I was hearing increasingly strange, disturbing, and frequent stories on the radio broadcast news. I heard that 1) someone was actually going to get the legal right to display advertisements on the moon, 2) scientists had found a way to transport a photon, and 3) someone had intentionally set a person on fire. My sacred public radio news, my favorite source of stories and ideas when time for reading became a luxury, was starting to seem unreal.

I swore I would never digest the news from television, but the next set of frightening stories I remember were the ones I indeed watched when my best friend was an actress addicted to soap operas. As we chattered about, dreaming up fantasy careers for ourselves, her eyes glued to the soap, my eyes glued to her, in her elaborate make-up procedure, we were interrupted by the televised Columbine murder scene. Shocked, and horrified, I felt the televised story turn to oatmeal pouring into my eyes, into my brain. Within months--or was it weeks?–the kids killing kids in school, these murders were being replicated around the country. The reports sounded off like a deformed bullet ricocheting in a holographic chamber.

I began to feel I could not read one story at a time; I could not find my own original story. I could not find Integrity. Once I had glimpsed her in an old woman’s repose. Fifteen years later I can only see my memory of her. Three weeks ago I saw a few minutes of a scene from a horror film displayed on a news broadcast. Everyone says it was real. I heard part of the story on public radio. Everyone is telling me what happened, and they are all saying something different. Everyone is watching the story as it is re-veiled on t.v. I decided I can’t. I decided to boycott the oatmeal this time.

I guess that’s how I wound up here, in the Uni-tale Universe. Apparently, someone here wanted to experience multi-story life at the same time that I wished to experience one-story life and a trade was arranged, although I haven’t yet figured out how that happened without my conscious consent. I don’t mind anyway. I want to explore and when I am done, the story I know should only be one.

Here a story can only be told one time. This is a Natural law here, comparable to our laws of Physics, immutable, irreversible. What happens if someone tries to re-tell a story or duplicate a once-told story here? I will have to ask, but first the Uni-taleiens have asked me to embed this in my story:

Oh beautiful reader, calm, near: Hear what we write upon your heart’s ear. From the land of the Uni-tale, the land of cherished stories, whose authors we revere, perceive a new vision; feel every angle of our interior.

Here, the physical laws dictate that a story may only be told only once. Feel our despair, though we are naturally joyous, we are imprisoned by our laws of physics that limit us to telling a story only once. How we crave to hear our cherished stories cooed into our ear repetitiously, like a mantra: secure, secure, secure. How we long for the deeper bond we can share, how we long to meet a tale transformed, ourselves transformed, or find the mutually transformational relationship you enjoy with your stories. We want to eat the Group Thought Soup we’ve heard exists in your world.

If this be our first encounter with the Multi-tale Universe, as is suspected by the Memory Bankers, then this singular mail, if it reaches you your world, may cause a collision of our two universes. We don’t know what will happen then, but we are so desperate we will take the risk.

We desperately seek to learn the technology that enables you to re-tell stories. Since we cannot copy in whole, or in part any story, we may not benefit in many ways. Our scientists must rely on nature to inspire their minds, to act as the corpus-collasum, as the bridge between fact and imagination that leads to new discovery.

One of our scientists believes you have a counterpart law of physics: that energy cannot be destroyed or created, only changed. The physics here dictate that no thought can be destroyed or created, only changed. One of our Fully Bright Scholars, the first to find a way to communicate a tale to all of us at once, as if we all shared one pair of eyes, through the use of electricity and some raw materials, the Scholar created a network that could display the same story in multiple places at the same time. the Scholar believes this is a monumental breakthrough in the search for multi-story technology.

You may wonder just what the one-telling law applies to here since where you are a story can be one of many things: gossip, news, a show, history, the description of a dream...a song? What is a story, what is a tale?

A story is a radio wave solicitation from one universe in search of another, a homing device sent out from one mammal in search of others, awaiting a response, anticipating a connection, lost if returned with only echoes.

Perhaps you can benefit from our uni-tale system: memory is better, cherished stories must be remembered since even if they are written they cannot be duplicated. The person with the cherished story is wealthy indeed. Some communities have no beautiful stories, they are destitute.

(Sorry, the transmission of the end of this story was lost somewhere in between multi-story land and the uni-tale universe.)

Why do we not want to revise our stories? Because we've become comfortable with the old stories.

We don't want to revise them because it will mean that we must go through a painful upheaval and

discomfort to develop a new story. We fear that the new stories won't work for us and if we've already

abandoned the old stories, we'll have nothing to fall back on.

But, if we become uncomfortable enough--as we all did on September 11, it becomes necessary to revise

our stories. With the new knowledge that terrorists can live anonymously in our midst and that they are

willing willing to turn planes, trains, and other vehicles into bombs, we must revise our stories. We'd never really

thought of that scenario before in this country.

What were comforting stories in the past--knowing that in fairy tales the bad people get punished--no

longer works as a way for us to confront our fears and to help us define good and evil.

What causes us to rewrite our stories?

We need to revise our stories to help us make order of our world. We all have a need to tell ourselves and

others when we acquire new knowledge.

Foucault uses the analogy of recognizing a face. He says that we "know more than we can tell." To recognize

a face, we could look at a picture of it. This might not work, however, when the person's actual face is

viewed because you need more knowledge of that face than can be presented in a picture. To be

able to recognize a face and better know a person, you need to be able to see that face from all angles.

You need to see the face smile, frown, show expression and emotion. Only then do you know the face well

enough to recognize it when you see it again.

The same can be said of our need to rewrite stories. We can read an old story or listen to another's story, but t

to make it work for us in the present, we need to examine it from all angles. We need to add our own

knowledge to the story. To make it work for our own needs, we need to feel the story, see its expressions, its

beauty, its warts--just like recognizing a face. Only then do we have enough knowledge to tell a new

story.

The Sound of Letters The act of reading is usually considered a mental activity. The point of reading, we are taught, is to understand what is written. Literacy, wherever it is found, begins by learning a set of symbols: letters. At first, letters seem to be the designated representatives of certain sounds, however, they don’t capture the variety, or the full range of sounds experienced in the typical fledgling human consciousness. Who decided which parts of the infant gurlging, gahyahing, and oohing, or the adult grunting, groaning and umphffing would be the chosen phonemes, the preferred units of sound, to be elevated to symbolization? Furthmore, why was sound, the human sound, elected to the impossible task of both representing itself, the symbol of itself, and ultimately, when ordered and combined according to the code of language, carrying messages, thoughts, and ideas away from one person and into another?

Perhaps the letters do not symbolize sound. Perhaps it is the other way around, and the letters existed once void of sonic conveyance. The letters, then, must have symbolized something else, certainly we agree that they must have symbolized something originally. In the museum of archaeology, looking for the answer might result in quite a surprise. The scholars have evidence collected, ancient objects found, that show that the earliest form of recorded hand-assisted thought transmission existed first as pictographs, drawings of everyday objects and scenes. The old stones show how the drawings evolved as the drawers, the artists, who were evolving too, simplified what they drew. As happens with simplification, paradoxically, the drawings became abstract; simpler, yet more complex.

Now, in reading what I wrote, I feel as helpless as a sound, ordered to represent itself, the symbol of itself, and charged with the transmission of the truth. Who invented the symbol for infinity, that twisted loop? The possibilities multiply the longer one considers the meaning of these physical marks, these groups of tiny drawings, these brain invaders; letters. Words.

What occurs to me when I investigate the markings I made when I was asked to write a fairy-tale the day before the mass murder at my country’s door to the world, New York City, a city I loved, is that I am here alive and my friend is at home with her husband staring at Saran-wrapped leftovers from Saturday’s memorial that was held for their 24 year-old son, David. His father said "So long, son," in his usual way the morning David left to meet a client for a rescheduled appointment, only three blocks away. David, of course, arrived a little early for his appointment; people who know the kind of elevator delays that can arise in navigating the way to an office 100 stories high, know to go early. While we students that morning prepared to discuss the meaning of fairy tales, the hour approached when David’s father would see a giant airplane used as a bomb plunge into that building with its hundred stories, and in less than an hour the structure was no more; powdered cement on the ground was now the 100th floor. When the World Trade Center fell, all the office debris flew into the vicinity. All the paperwork people had said they were buried under was working its way down and around, falling much slower than the burning bodies, down to the tomb.

The World Trade Center was like the United States’ penis; New York City was like its womb. That’s the first set of words that came to my mind when I saw the attack from the seminar room. My mind perceived an abbreviated message transmission via the WTC, the very place where I had increased my vocabulary by at least a thousand acronyms. In my head, guts, and glands, I felt the message, vulgar and profane, I felt my country’s pubescent exuberance had been slain. We didn’t get to discuss our reading from Robert Bly’s "Iron John, A Book About Men," but these words: Iron John Robert Bly Book About Men, these words will for the rest of my life carry to my inner ear the silent bomb that reduced me to fear.

David’s father received a message, too, as he cried to God to send him a sign, to tell him if he looked for his son, what would he find? Out of two buildings, so tall they were like marks drawn by a giant in the sky, a signal to traveler’s that NYC was nearby, a single piece of paper was heard colliding against the fabric of the suitcoat David’s father wore as he walked toward the death heap. The sound registered in his ear, the tiniest pressure from the edge of paper traveled through his coat to his skin, and reflexively he plucked the thin sheet off and looked at it. Within two seconds what was written got to him. His son’s full name was written near the top of the sheet because it was an invoice for services rendered by his son.

This story is more than the letters and words organized here. As representatives they can never completely report all the experiences of September 11th, 2001. Certainly no one can make marks that tell the experience of the murdered.

Our marks and scratches, our attempts to explain human —human-generated!— atrocities to ourselves and to those yet to be born, our thoughts and ideas arising from the pain, are impossible to contain in physical form. We may find the strangest messages carried into our brains on seemingly unrelated words. This is what happens when I read what I wrote to myself. I get messages that are more than the combined definitions of the words.

First, I see the image of the first paragraph as an abstract shape shaded in with marks. The shape with its sharp point aimed at the text below gives me a sense of being attacked. At the same time it looks like a dancer; I find myself in a state of emotional ambiguity because I know the shape is abstract and my mind is for some reason choosing these images. Before I begin to read I feel physically provoked because I am forced to discard my habitual way of reading: left, right, down, left, right, down. The arrangement of the words in a different way makes the words unfamiliar so that they bypass my automatic dictionary. As I navigate the text and hit space instead of the end of a sentence I feel a little abandoned, pushed into uncertainty, this changes my perception of the next group of words. Soon I feel so physically manipulated that it is as if the writing is dancing with me, but it is the leader. This physical sensation heightens my other senses; I begin to experience the words rhythmically, as well as visually and physically; the meaning of whole sets of words comes in last. Once I adapt to the disorientation, I begin to experience the space around the words as quietness that invites meditation, and a restful place for thoughts.

As I continue to investigate the marks on the page, echoes of words and echoes of meanings combine in the way that ripples combine when two pebbles are tossed close together onto a placid lake. The combination of words that echo a sense of the ancient combines with the words that echo futuristic. "Sun," "old gray rock," and "stone," for example, ring ancient while "black hole," "polymer," "ultra-violet silicone," and "lost keys" ring contemporary. The two together create a broad perspective of time.

When the words "cried," "heart," "naked," and "bruised side out," collide in my mind I sense pain, and the vulnerability of facing pain and suffering head-on. "Brother planet" carries an image of kinship and an assumption that earth is the sister planet to my imagination. The chronological aspect of the story moves forward in time, then goes a little bit back, forward in time again, a little bit back, in the way that waves do. This coincides with the emotional waves, that like nausea, washed over me repeatedly during and after the terrorist attacks, but I am uncertain as to whether this effect will be transmitted to other readers. Since I know what I felt as the images came to mind when I wrote, I find it impossible to judge whether or not they even make sense to anyone else, and I wonder if this writing has any meaning at all outside of the context of the insane message sent to our country on September 11th.

Works Cited

Abbott, Edwin A. Flatland. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1992.

The Fourth Dimension’s Version of the 3 Dimensions

I call our world Timeland, not necessarily because we call it so, but rather to make its nature clearer to you. I don’t know exactly how to describe this world, nor whether it is even worth the effort to attempt a description. I know you beings accept the three dimensions of width, height, and length, and that you interpret the world around you accordingly. Well, picture a world in which the three dimensions are length, width, and height, but these are interpreted according to the past, present, and future. Since I know how confused you must be, I will offer an example for your puny minds. When we look at the sun, we are able to see a speck of dust, a swirl of gas, a mighty sun, and a terrifying darkness. These images are not as blurred as you might imagine, but rather we understand their dimensions and position in time as clearly as you understand which lines of the cube are furthest from you and which are closest. You see, the fourth dimension is time, and our world is the essence of time. We are a world in the sense that we exist among you, as one of your unseen dimensions, as a universe known to only the deep recess of your mind. We are the ones responsible for the time aspect to your life, the baby fat and the wrinkles, the arthritis and the metabolism. We are the ones responsible for changing the story of your life. We are responsible for rotating the cube, for bringing those distant lines to the foreground of life, for merging the future and the past within the realm of our control known as the present.

Now I know what you’re thinking, and I’m telling you right now to relax. It’s not as complicated as it might seem. Time is a dimension already existing as a part of you; it is just an invisible part. You see, every decision you make in life (and everything from movement to zoned out silence is a decision) we interpret the future this decision makes, and we move the future consequences forward. Like a cube, some of the points on the line take longer to move forward than others, hence, you acquire wrinkles slowly but hair grows quickly.

This has more of a consequence than you may realize. Time controls your entire life, and we control your entire past, especially your history. Your history, you see, is not a line of facts and dates but a constantly evolving story of potential, realization, and interpretation. With time, everything changes; the cube rotates; we create a new story for the making. But this new story is not altogether new; you see the potential for a new interpretation is “already there, waiting in silence for the moment of its expression (Foucault xx.)”

However, there are impossibilities within your three dimensional world, interpretations you are not able to realize until the timing is right, until it is declared and destined that it be seen. In other words, “the unthinkable is that which one cannot conceive within the range of possible alternatives, that which perverts all answers because it defies the terms under which the questions [are] phrased (Trouillot 82.)” Allow me to demonstrate once more, for your sake. If you lived on a plain, a two-dimensional plane of existence, it would be “unthinkable” for you to see three dimensions because every question you ask is framed with an assumption of that plane. You humans think linearly, and so every assumption you have you always assume to be constant. Life will always be defined by that plane because everything is currently defined by that plane. The potential for the linearity of life to bend is a denial with you beings. No question is able to pierce that ignorance.

Why is it so impossible to pierce through that mindset? All this must be terribly confusing for you, especially since I have already mentioned that the deep recess of the brain accepts more than three, even more than four dimensions. Then why can’t you accept them? Very simple, you have been handed down the plane form of existence; you were brought up believing in the line. Children, however, are instinctively curious and able to question; they are able to picture other possibilities even if they “don’t see how (53)” this other possibility could be a part of their reality. This sort of curiosity would make a child a “fool (54)” even if the child is perfectly correct. You are taught how to see the world, and you are taught by which questions and terms you are to define it. You people have a necessity for lines, for clarity, for rules.

You see, that is where time comes in. We are an earthquake, I suppose, to the linear ground of your structured world. When the time is right, we shake the world up a bit. It is as though a great Sphere of knowledge descends every millennium to reveal another layer, another part of your world. This does not mean we reveal ourselves, nor does it mean we reveal dimensions. Rather, this means we reveal a new story, or rather we change the world by bringing out a new potential, a new side, to the same story.

If, for example, we were to take a figure from Flatland and show him your three dimensional world, he would declare “behold, a new world (64.)” For him, this would be a new story, and so he would be forced, most likely, to write some absurd book or make some bad movie rewriting the story of his plain, of his Flatland, to incorporate this “new” third dimension. As time demands, your story is changed, and so you beings, obsessed as you are with detail and linearity, must rewrite the story correctly, starting off, of course, with the world in which you previously lived. To rewrite or revise a story there must be an original, and so the original always comes first, even when rewritten, if simply to mock and satire the errors, but more commonly to make obvious the “newness’ of the world.

Perhaps the sad part is that there is no help for your perception, no help for the world. No story is ever rewritten; no world is ever “new,” only redefined. The potential exists, but the structure of life and the varying dimensions are always too strong. Only accepted ideas are transcribed into the culture, into the world. The rest remain a figment of the imagination or the reality of a mental patient.

But, since you live in the three-dimensional world, you are required to rewrite the story of life and history as the story unfolds and as time changes the definitions. Everyday a little bit unfolds, and everyday you adapt and accept the new terms. There are too many possibilities in life for you to accept them all, not if you want to maintain order and structure, not if you fear change. So the story changes rather slowly, and only in moments of complete chaos and melancholy is the story ever replaced with an entirely “new” account of the world. Whether this be a “Colour Rebellion” or the opening up of a new dimension, these changes are rarely as sudden as perceived, and they are rarely as lasting as they are promised to be. And yet, they are essential. The reinterpretation and the retelling of stories remains the only means by which time is measured, and the only ways in which the world revolves and its people progress through life. You need the ground to shake just as much as you need the structure to hold strong. This is a necessity.

The story of life is much like a fairy life; you beings you could recite the tale by heart. The story is what defines you. As you change, as time changes you and the world, aging you slowly, the world is redefined and rewritten by new terms. The story is constantly revised, constantly rewritten because you are constantly comparing the “old” with the “new.” You are always discovering and exploring, sometimes by force. The world is less stable than you claim, more complex than you see, and more ancient than you could imagine. But the frontier is always expanding, and the story is constantly changing by the dictation and command of the mighty fourth dimension. We are the ones who rewrite the story through the accumulation of change and time, through the exposed possibility of potential.

I think it’s part of human nature to re-tell a story, only because it would allow them to set the story right or make any changes they deem necessary for the betterment of the tale. Perhaps it’s because they have learnt something new, or perhaps it’s because they simply don’t like the way it ended (think Disney and ‘The Little Mermaid’), or maybe it’s just the case of not recalling the exact facts. When stories are passed down from generation-to-generation through word of mouth, it usually loses some of the lesser details while new ones seem to spring forth. Much like a game of telephone, where you whisper a phrase that is to be passed around a group a people, the end result can sometimes not be remotely similar to the original phrase.

On the other hand, however, we are reluctant to go ahead and re-tell a story because we might change it, or taint it, or do something that’ll absolutely ruin it. It’s that hesitancy that keeps us back from changing something told, because sometimes things are best left alone. Other times, however, they just need some shaking down to get them ready.

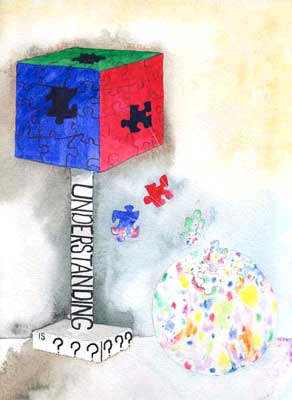

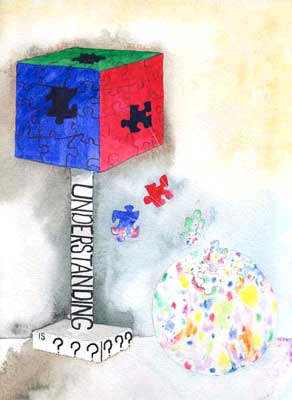

Changes are, I believe, something that is essential. Perhaps knowledge that the stories we hear today might not be the exact ones told to family members long before they thought about writing them down is reassuring, because it shows how society has changed. Of course, we might lose the knowledge we had of what came before the change, but if the new change isn’t for the best, it can be changed once more to fit an adapting society. It also might be that we need to be proven that there isn’t just one correct form of a story: there are various views that should be analyzed and put together like a giant jigsaw puzzle.

Works Cited

Works Cited

Meg Devereux

Science asks,

This creation is one of a multitude.

Science says, there are many answers.

Art asks,

This word can attach to that word and become a poem, myth, saga.

Art says, there are many answers.

Religion asks.

This creation can be a wholeness.

Religion says, there are many answers.

The child asks,

This child can observe the cells on his skin.

The child says, I have many answers.

Evolution by natural selection is the scientific version of the story of earth. Most of the scientific community accepts the idea of evolution as an explanation for the biological diversity of life on earth. They agree that the earth is billions of years old and that millions of species of living things evolved over millions of years into their present forms. The theory of evolution has been studied and supported scientifically since Darwin and Wallace proposed it simultaneously (Is this true? I forget the details, but will fix in my revision.) in the mid-1800’s. Data have been presented and analyzed in the fields of geology, paleontology, genetics, and many other scientific disciplines. As in all of science, the theory of evolution has been assembled from a system of ideas and concepts that make sense of all the data. As is true of all theories, the story of evolution is always open to revision.

If we review the scientific method, we see that the nature of science is that it is always testable. It is based on inferences that are supported by observations and collections of data. Science is always open to debate and controversy. Science must follow the steps of observation, hypothesis, experimentation, all in light of the most certain of scientific statements—laws. Laws are considered to be facts, cases in which a contradiction cannot be conceived of and none has ever been observed. An example would be the law of gravity.

Creationists, who believe in the story of Genesis and sometimes call themselves “Scientific Creationists,” violate all the rules of proper science. They begin their studies with a belief system and then set about to provide explanations. This is a backward approach to science. A scientist sets out to test and validate theories and then acknowledges the results, come what may. Creationists, because they have a literal belief in Genesis’s account of the origin of life, seem to believe that their argument needs no testing. They simply gather evidence that seems to validate their already-established claims and they discount all other evidence. This might be a valid approach to theology, but it is not to science.

In their “creation-science” biology textbook, Of Pandas and People, Percival Davis* and Dean Kenyon present their evidence of what they refer to as an “intelligent design” as a way to reconcile their belief in Genesis with their knowledge of science. For example, they point to the gaps in the fossil record as evidence against evolution. They maintain that fossils which show a gradual change from one species to the next should exist, and that they just don’t. Their conclusion is that, therefore, all species were created in their *Really Bill Davis, a lapsed biology professor turned creationist professor.

“Does the fossil record provide any evidence for either the evolution or the intelligent design of man? It is interesting to note that in his book, The Descent of Man, Darwin did not cite a single reference to fossils in support of his belief in human evolution. Clearly his original idea of human evolution did not grow out of a study of human fossil evidence, but out of a previously held opinion about the origin of man. The same is true of many researchers today. Since Darwin’s time, evolutionists have been searching for fossil remains to establish their views that man evolved. Despite the absence of transitional series, this position is held in the expectation that the evidence will turn up…Meanwhile, it is easy to assume the idea of human evolution has been confirmed just by the confidence expressed by many biologists in the essential correctness of evolution.”

Is it possible to reconcile a belief in divine creation with all the available scientific support for the theory of evolution? Should we even try?

I think that we should view Genesis as the fairy tale version of the story of earth and evolution as the scientific version of the story. We should not try to reconcile the two stories but simply respect the needs they fulfill for different kinds of peoples and cultures. We should not abandon the old stories and simply replace them by new stories. Instead we should recognize that whatever comfort we find in any version of our stories is just that—comforting.

References

Dorit R., et al. Zoology. Philadelphia, Saunders College Publishing, 1991

Campbell, N. A. Biology. Menlo Park, Calif., 1987

RE-TELLING STORIES

As individuals we are motivated to share stories that entertain, inform, instruct, influence, enlighten, and heal. The most important stories we tell, however, are those that order our world and our place in it. And when we tell a new story of our world it is possible that some will hear it as a threat.

Evolution is the secular story we tell of our origins. It is a story made possible by the Western world's exploration of humankind's place in the universe through the method we call 'science'.

The uncertainties that are part of science, anthropologist Jamake Highwater writes, have been most acute with the advent of Twentieth-century science where strict laws have been "ignored in the pursuit of a worldview that requires subtle and flexible truths." But this uncertainty is also a challenge inherent in the "emergence of a relativistic viewpoint" in our Twentieth-century culture (40).

Some people experience modern culture as chaos. There are new roles for women to be sorted out; demands by people of different cultures that their voices be heard; and the challenge to authority by our young people. The list of forces re-ordering our world goes on and on. Modernity can seem threatening to a person for whom the old order reflected all that was right about the world.

"With [the] constant onslaught of observations and hypothesis that countermand the rituals of Judeo-Christian dogma, and with today's deeply felt and daringly facilitated humanism, the first shock waves of a 'cultural earthquake' ... have aroused in us the possibilities of Western transience and fallibility" (40).

The attempt by Creationists to re-tell the Genesis story in our public schools is one response to 'the earthquake' of uncertainty. It reflects a desire to return our society to the comforting certitude that the religious way of knowing is meant to provide. Creationists desire to assert a public role for religion in a society they feel has moved away from God; a society that has delineated a separation of church and state, a separation of the secular public space from the private religious space.

The strategy Creationists devised for bringing religious belief back into our secular space is the re-telling of their Genesis story in the language of science. In the United States, they have been organizing to reassert such a place for their Christian understanding of the world since the founding of the Religion and Science Association by George McCready Price. Price was a Seventh Day Adventist who in 1935 published the "New Geology," which argued that all geological features today are the result of Noah's Flood.

Henry Morris, the father of modern Creationism, is credited with setting into motion the use of scientific data as a "tool for bringing people to Christ." He began presenting the Flood geology model as an "alternative science," strategically avoiding any mention of the Bible, or of Christ as the Creator (Nelkin, 78). Such omissions led to an outcry from other Creationist thinkers who complained that, "One might just as well be a Jewish or even a Muslim creation scientist as far as this model is concerned" (246).

However, Morris' re-telling was useful to the Creationist movement for several reasons. Chief among them is that American society believes in science as a way to understand the world. In the Creationist's re-telling of the Genesis story the movement benefits from the legitimacy of science. In Morris's words, "Creationism is on the way back, this time not primarily as a religious belief, but as an alternative scientific explanation" (16).

This residual legitimacy has had its rewards. Creationists have gained access to the media (as seen in the articles accessed at our various websites). And most significantly, this borrowed legitimacy provided access to local and state legislative decision-making processes. It made it possible for Creationists to have "Balanced Treatment" laws passed mandating equal treatment of evolution science and creation science in the classroom. In anticipation of success, Morris even wrote the definitive book on the science of creationism, and designed it to be suitable for use in school biology courses (16).

The Creationist's claims to science have been fully refuted. The National Academy of Sciences website states that: "Scientists have considered the hypothesis proposed by creation science and have rejected them because of a lack of evidence. Furthermore, the claims of creation science do not refer to natural causes and cannot be subject to meaningful tests, so they do not qualify as scientific hypothesis."

Others have addressed the specific scientific points made by Creationists, including those put forth by the intelligent-design theorists who Robert Wright agrees "are more sophisticated than past creationists." But he goes on to say that the movement's critique of evolution is nothing new. It is "just a fresh label, a marketing device" (slate/Earthling). In a 1987 ruling, the United States Supreme Court agreed. It declared that creationism is religion, not science, and cannot be taught in the classroom.

The story of evolution is, undeniably, our dominant creation myth, but the Genesis story will continue to be told because some find comfort in it. However, the Genesis story re-told by Creationists has no place in our schools. The classroom is where our children gather to hear secular storytellers, our teachers, pass on a view of our origins we can all believe in.

Tuesday I trudged around campus feeling lousy. I had a banging headache, over-caffeinated nerves, and my eyes felt like they were about to be catapulted out of my skull if someone were to let go of the rubberbands holding them in place. Just your typical pre-break Bryn Mawr woman, right? Except that none of these symptoms had anything to do with fairy tales, Foucault or Galileo, but in fact had everything to do with my nightly visitor.

Thomas, my four-year-old son, has been paying me visits in the wee hours of the night for the last four weeks or so. Most times, he doesn't say a word, but even in my deep slumber, I can sense his presence, hear his breath and I awaken to see him standing by the bed. "What is it, Sweetie?" I ask. He replies in a whisper "Nothing, I just want to look at you."

We walk together to his room, where I wrap him in his favorite blanket and we rock in our favorite chair, saying nothing, and for the moment, we are both blissfully content.

But oh the consequences of interrupted sleep.

The truth is, my little guy is not adjusting well to Mom's new world/hours. He's always been a Daddy's boy, so I admit to being a bit surprised by his sudden emotional state. With my absence from his world --even though it's only two days a week -- he seems to have suddenly fallen unabashedly in love with me.

I'm exhausted. Anyway, did I misunderstand something? I thought we didn't have to write about evolution vs. creation? I guess I'm still stuck on why we change our stories. Sorry everyone.

The course's theme has to do with getting it less wrong -- but I fear I'm moving in the other direction -- I'm getting it less right.

Changing/Replacing Stories

Our narratives have to evolve with the times in order to reflect changes in society, but we don't necessarily replace earlier stories, so much as we update or add to existing ones.

With most of these updated publications I have no way of knowing how, where, or why it was changed, and I find myself wondering what transpired in those years between editions to convince the authors they needed to revise their story. What exactly did they feel a need to change, add, or delete? Why couldn't the publisher have chronologically color-coded the text, so that I might see for myself the irrelevance of the now missing data?

Dr. Spock had openly opposed nuclear technology and the Vietnam War, and he joined young people in their public protests. He was arrested and convicted for conspiracy to aid, abet, and counsel young men to avoid the draft. (The verdict was later reversed on appeal.)

It's curious that Dr. Spock felt the need to use space in his 1985 book to update his readers on those events from years ago, defending his work. He claimed those who had harshly criticized his writings and philosophies at the time did so only because they had political differences with him.

In comparing these two editions, I expected the older version would seem naïve to a parent in the 21st Century. I expected a few chuckles at its expense, and when I came across the sub-heading "Why not the stork?" I was confident it would provide the necessary material. It didn't. Oh I smiled, but more because the good doctor had impressed me with his solid opinion on the consequences of lying to children about where babies really come from.

One of the illustrations in the old book was rather poignant and telling. It depicted the new father viewing his newborn for the first time -- through a glass window. In those days, the father was not permitted in the nursery, nor allowed to hold the baby.

Forty years ago Dr. Spock chastised those who believed that the care of babies and children was the mother's job entirely, stating "You can be a warm father and a real man at the same time." (Two steps forward.) He then added, "Of course, I don't mean that the father has to give just as many bottles or change just as many diapers as the mother. But it's fine for him to do these things occasionally." (And one step back.)

Dr. Spock was an astoundingly progressive thinker in 1945. He addressed issues such as puberty, masturbation, sexuality, fatherless children, handicapped children and adoption. The newer version adds a variety of topics such as: Child Abuse and Neglect; Enjoying Your Baby; Learning to Parent; What are Your Aims in Raising Children?; Parents are Human; etc.

Dr. Spock was nearing his 80th birthday when the 1985 version was published. He stated the main reason for this fourth revision was "…to introduce a collaborator and co-author, Michael B. Rothenberg, M.D." He felt this might be his "…last chance to work closely with a successor and ensure a smooth transition." (Another edition was indeed issued in the 1990s, but was not available to me for this piece.) Dr. Spock died in 1998 at the age of 94.

It seems there can be no final edition in our ever-evolving world. Dr. Spock came surprisingly close.

References

Spock, Benjamin

Spock, Benjamin and Rothenberg, Michael B.

"United States," www.channel2000.com (Copyright 1998 by The Associate Press)

Galileo begged the people to understand that the universe was heliocentric. Like those in Flatland who refused to believe in a third dimension, the people refused to believe in Galileo’s theory. They were too closed minded to go beyond their conventional beliefs and accept these new ideas. Galileo was reluctant to tell his tale because he feared ridicule and even worse consequences, but he was also motivated to reveal the truth and expose the world to a “new dimension” of thought.

There were many costs Galileo had to pay for telling and not telling his story. It was dangerous to reveal his theory about the Earth. At that time, science was still entwined with religion. The Vatican was in charge of Italy, and therefore science. The Inquisition believed that Galileo’s Heliocentric Theory went against God and the church. They threatened to torture him if he did not disclaim his original-- and what was to them outrageous-- theory. Galileo went along with them, but later he still found a way to reveal the truth and revolutionized scientific thought. He had been afraid and reluctant to tell his story, but he always remained eager to enlighten others to the truth.

People today still try to view science with a religious base. Creationists and adherents of the Intelligent Design Theory explain the origin of human life and the Earth based on the belief that a higher being designed the world. They believe that evolution goes against the Bible. They tell their stories to prove that evolution is not a legitimate way to explain the origin of life. Supporters of the theory on evolution claim that creation science lacks pragmatic support and cannot be significantly tested. Scientists of all views, aware that others will attempt to disprove their theories, continue to strive for understanding and truth.

Scientists hope that by exposing the world to their stories, the truth will be learned. They persist in their search for evidence to prove their theories. By exploring the world of science, they enhance and enlighten others. The contemporary debate about science education will continue for many ages, and people will continue to reveal stories in the hope of uniting the world.

Paper #2: Why We Re-Tell Stories

In his Preface to The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, Michel Foucault reveals a primary concern in his investigation: "observing how a culture experiences the propinquity of things, how it establishes the tabula of their relationships and the order by which they must be considered" (xxiv). In other words, Foucault strives to create order in a disparate universe: to characterize, to categorize, to define, to differentiate - namely, to arrive at some semi-satisfactory state of understanding that accounts for the vast inconsistencies that populate the world. Does this sound familiar? Of course: it reflects the end toward which humanity has been striving since the origin of thought. Do we not inherently realize, as Foucault puts it, that "a 'system of elements' - a definition of the segments by which the resemblance and differences can be shown, the types of variation by which those segments can be affected, and, lastly, the threshold above which there is a difference and below which there is a similitude - is indispensable for the establishment of even the simplest form of order" (xx) and consequently wish to act upon this idea? We do, a fact evident in our explanation of the biological hierarchy of life; in the construction of countries, states, towns and other non-natural borders; even in the divisions in our schools as to graduating year, academic field, extracurricular interests, and the like. But Foucault's purpose is not nearly so simple. He sees a spectrum of knowledge ranging from this "system of elements" or "fundamental codes of a culture" (xx) at one extreme to the "scientific theories or the philosophical interpretations which explain why order exists in general, what universal law it obeys, what principle can account for it, and why this particular order has been established and not some other" (xx) at the other. Between these extremes, he finds "the pure experience of order and of its modes of being" (xxi), the springboard for his ensuing "archaeology." In sum, he believes that he has found a fresh approach in humankind's epistemology and so wants to re-tell "the order of things" in relation to this new inspiration.

Works Cited

National Academy of the Sciences. “Evidence Supporting Biological Evolution.” Science and Creationism. http://www.nap.edu/html/creationism/index.html

Heinze, Thomas F. “B3-The Pillars of Evolution.” Answers to my Evolutionist Friends. http://www.creationism.org

Glanz, James. “Evolutionists Battle New Theory On Creation.” New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2001/04/08/science/08DESI.html?searchpv=site08 (8 April 2001).

Creationism and evolution are such ideological ideas in today’s society. To believe in one idea is to discredit the other idea. Science can be used to support both ideas, and each side can find holes and errors in the other side’s arguments. The accusation from both sides is that the other tries so hard to prove their point that they don’t take into account all the other facts. There is still a long way to go to proving either theory correct, which just helps both sides find ways to argue the other side is wrong.

For many people, the creationist view is the first story they heard about the beginning of people and the world. Many of these people also chose to follow the Bible story as their guide to establishing their life's purpose. For these people, the creationist view satisfactorily answered their question, and this is the story they believed to be true. Therefore, when Darwin or the other evolutionists came along and questioned the story of the creation of the earth, it caused these people to have to question the world, the Bible, and their purpose in life. Some people were willingly to do this because they saw the evolutionist's evidence and agreed with this new story. They were not upset by being forced to question their foundations if it meant gaining a better understanding of the world, an understanding that they believed was closer to the truth. This then could become their new purpose, searching for the truth, or they could develop another purpose. But the major point is that they were willing to change their beliefs because they thought that the change would benefit them in some way. Other people were not eager to change because change produces uncertainty. Most people don't like to feel insecure or confused about something. People like to have answers and understanding, not frustrating questions. Therefore, some people refused to accept this new story because they were satisfied with what they believed in the first place, they had established their life's purpose based on the Bible and didn't feel any need to change it because someone decided to retell the story. If they were to change their beliefs it would prove their previous beliefs to be wrong, and the deeds that they did according to these beliefs would now be considered a waste. Most people would not like to feel like they wasted their life doing the wrong thing, especially older people. In this case, the retelling of the story of the creation of the earth is harmful.

The debate over evolution versus creationism has greatly affected people, some beneficially and others harmfully. Anytime someone retells a story there are going to be those that welcome the change and those that don't. Often times there are more people who don't want to accept the change. This is why people are conflicted when they come across something that will change a story. On one hand, they are motivated to retell the story because they feel that their new evidence or perspective will help people to gain a better understanding about the subject of the story. There are also negative reasons why people retell stories, such as to purposely create confusion and frustration or to make themselves look better or more important. On the other hand, most people don't like change because it can make them confused and uncomfortable. People who believe that change is helpful to people will naturally be inclined to retell stories. Those who dislike change will be reluctant. Even though change may disrupt many people's minds, they also have the choice not to accept the change. This is why people should be allowed to introduce new stories, because every person has the will to reject it. This is why I think both evolution and creationism should be taught in school. Students hould be given the opportunity to look at facts fom both stories and decide for themselves which one they think is true. History has shown that stories are always changing, and it would be silly to immediately accept or reject a revised story without looking at all the information. Part of school is learning to make your own decisions, which is extremely important because every person will eventually have to make a decision about how to live their life. This is why I think it would beneficial for students to become comfortable with comparing and analyzing stories before they make a decision about which one they believe. Too many people don't think about why they believe in certain stories, especially important ones such as how the earth was created. Retelling a story can be very powerful, and one should always ask why they want to retell it before they do, so they can determine whether it is a good idea to retell it or not.