Wow. Resonances on multiple levels and in multiple ways. Happy to follow you in the direction of "survival and the animal/being", but let me put a few more things on this table first, and perhaps try to tidy up a bit here before we head out?

|

the unconscious processes information largely metonymically while conscious processing does so largely metaphorically

|

Your metaphor/metonymy distinction is an important one. And, as it happens, a familiar one. I was first exposed to it, interestingly, by a colleague in biology who borrowed it to try and explain the difference between scientists who base their work on spatial and temporal patterns in observations (metonomies) and those who instead develop and explore computational models (metaphors). It immediately struck me that that distinction might provide a way to make sense not only of differences and resulting tensions in the academic world (both intradisciplinary and interdisciplinary; cf Theorizing Interdisciplinarity: Metaphor and Metonomy, Synecdoche and Surprise) but also of differences and tensions between unconscious and conscious processing (ie within individuals, cf. Exploring the Consciousness Problem). And I continue to think that is so, that the unconscious processes information largely metonymically while conscious processing does so largely metaphorically (cf The Bipartite Brain).

So, I ask myself, why didn't I point to a metaphoric/metonymic distinction in our conversations to date? And why have I (I now notice) not used that distinction in some of the more formal writing I've been doing recently on these issues, nor in much of my teaching (though see musings)? The answer is, I think, very relevant to what we're trying to sort through. To use the metaphoric/metonymic distinction with most people one first has to teach it to them, and in trying to do that my experience has been that one runs into all sorts of complexities. Yes, indeed referring to a man as a "red beard" almost certainly reflects in its origin a substitution of one thing for another based on more directly perceived spatio-temporal relationships. But it has become by usage also "metaphorical", ie a substitution based not on the more direct experience of an individual but rather on having seen/heard that substitution being made by others. Conversely, some substitutions that clearly have their origins in metaphorical processing ("country" and "flag") may take on, for individuals, the "feel" of being related metonymically, ie without abstraction or thought (whether they ARE in fact represented metonymically is a very interesting neurobiological question).

It is not just that a distinction that seems so obvious and useful to some people (me and you among them) is less obvious to others but that it is less obvious for a particular reason: it is hard in general for people to get a handle on why they make particular associations between things. Moreover, the reasons may be different for different people, and may be different at different times for the same person. To put it differently, there is "story", ie what we consciously experience/think, and then there is .... what despite all our efforts we are less clear about, less able to be sure of (the unconscious, or "tacit").

|

My point in all this is not at all to quarrel with your suggestion that "story teller" is "metaphoric" ... I do, though want/need to contest your conclusion that the "I-function" [is] not.

|

My point in all this is not at all to quarrel with your suggestion that "story teller" is "metaphoric". Indeed it is, not only in the obvious sense that it is a language term (though I will argue below that language is not in fact necessary for metaphoric processing) but also in the deeper sense that it is a term more removed than other terms from what I (or others) more directly experience. It is a higher order abstraction, itself the result of a long period of negotiation between .... my unconscious and my story teller. And, as such, it reflects organizational features of both, most notably (because of the story teller) an inclination to try and find similar patterns in an array of different more direct experiences (this is "like" that, very much amplified and extended). From the latter, it is appropriately concluded, at the deepest level, that indeed the "story teller" feature of the brain encompasses metaphorical processing.

I do, though want/need to contest your conclusion that the "I-function" does not. That which is "more directly" experienced is ... experienced, and hence must, in my terms, involve the story teller. It must, at least to some degree, therefore be affected by the metaphorical character of the story teller, the effort to try and find common patterns across a wide array of different things coming from the unconscious. George Lakoff, in Metaphors We Live By and Philosophy in the Flesh provides a number of good examples of hidden "metaphors" in a variety of aspects of things we tend to think of as our most "direct" experiences. In his enthusiasm, I think Lakoff goes to far with his argument, implying that there is actually nothing BUT metaphor (which he confuses with categorization or abstraction, a more general process; one of the virtues of the story teller idea for me is that it helps to provide a needed distinction between abstraction and metaphor; more on this below). Nonetheless, Lakoff's examples provide strong evidence that there is some involvement of metaphor in everything we experience, no matter how "primitive" (or "animal") . The "I-function" is MORE primitive/animal than some other story features but insofar as it is experienced it is part of story and so less primitive/animal than others (cf "treeness").

|

I can't agree that the "I-function" is not metaphoric, but am willing to agree that the "I-function" is MORE "contingent to the being for whom the experience is being narrated as I", ie that it is CLOSER to .... what comes from the unconscious than some other things the story teller does.

|

In short, I appreciate very much your bringing the metonymic/metaphoric distinction to the table, and would like to keep it here, with the hypothesis (at least) that the unconscious operates metonymically and consciousness (the "story teller") uses metaphor as a way of making sense of what it gets from the unconscious. I can't agree that the "I-function" is not metaphoric, but am willing to agree that the "I-function" is MORE "contingent to the being for whom the experience is being narrated as I", ie that it is CLOSER to .... what comes from the unconscious than some other things the story teller does. And in this sense more "naked"

You'll notice that I'm avoiding saying, closer to "truth", replacing it with "what comes from the unconscious". As you say, there is no assurance that "when one says "I" s/he is speaking the truth". For similar reasons, I'm declining to make an epistemology/ontology distinction. In my terms, there is ONLY the things coming from the unconscious, and the sense made of them by the story teller. The problem of the meaning of things is inextricably entangled with the problem of what is, so there is for me no clear distinction between the two, no way to evaluate truth, and .... nothing but the unconscious, the story teller, and negotiations between the two.

|

Burden and Pollock were/are doing in art what Beckett and Virginia Woolf (sometimes) were doing in literature: exploring how to tell stories that stay close to the unconscious.

|

There IS though, for both aspects of story (experience) itself, and for different story telling styles ("primitive", sophisticated), a legitimate and appropriately noticed difference in degree of "nakedness" in exactly the terms you define it: Burden and Pollock were trying to make evident themselves, their "I"s, rather than their more abstracted understandings of other people or the nature of art or .... any of the other things more distant from the unconscious that artists (and others) sometimes try to make evident. Your use of the "I-function" to signal this is entirely appropriate. And my insistence that the I-function is a subset of the story teller shouldn't in any way detract from that. Burden and Pollock were/are doing in art what Beckett and Virginia Woolf (sometimes) were doing in literature: exploring how to tell stories that stay close to the unconscious.

|

you've more than persuaded me that "I-function" and "story teller" should not be regarded as alternate terms for the same thing. ... I will keep "I-function", and use it happily in the extended senses we've discussed. I do, however, still feel a need myself to move beyond "I-function" to the more encompassing term "story teller", and perhaps to persuade you that the more encompassing term is at least as interesting as the term it contains.

|

The bottom line is I'm not any longer trying to to "substitute" "story teller" for "I-function". I'm not actually sure I was originally, but agree it sounded enough that way to justify your concerns. In any case, you've more than persuaded me that "I-function" and "story teller" should not be regarded as alternate terms for the same thing. Game, set, and match to you on this issue. I will keep "I-function", and use it happily in the extended senses we've discussed. I do, however, still feel a need myself to move beyond "I-function" to the more encompassing term "story teller", and perhaps to persuade you that the more encompassing term is at least as interesting as the term it contains. Let me try and say why.

What seems to me appealing/useful about the primary subdivision between unconscious/tacit/metonymic and conscious/story teller/metaphoric is not only that it is at least reasonably well-defined operationally (and at least partially so neurobiologically) but that it provides a framework for making some other distinctions that it seems useful to be able to make. The distinction between abstraction and metaphor, mentioned above, can, for example, be made in terms of the absence or presence of evidence of "an inclination to try and find similar patterns in a wide array of different more direct experiences". Perhaps more immediately germane to our conversation is that the primary subdivision provides the basis for substituting for the more awkward concept "truth" the somewhat better defined "comes from the unconscious". The "I-function" is not in any sense closer to "truth" than some of the other things your colleagues in art history work with (more on this below), but it IS closer to the unconscious.

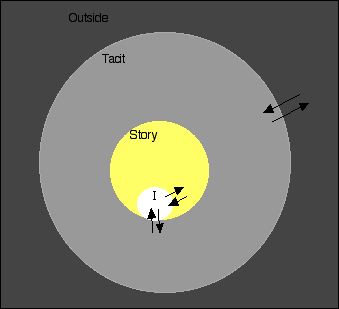

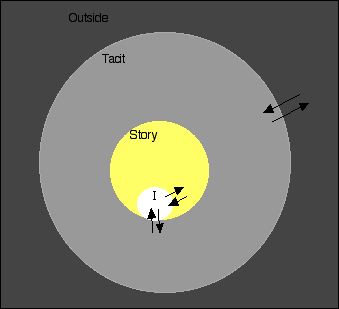

Maybe (inverted postures again?) some visual images would be helpful at this point. As shown to the right, outside our nervous system is ... darkness. Inside the circle of our nervous system there are various degrees of light. Through interacting with the darkness (as well as via genetic transmission) our nervous systems acquire "tacit" knowledge; the grey circle includes all we know without knowing we know it (and without any experience of it). It is not only the basis for much of our action but the only source of information for the inner part of our nervous system, the story teller, and the only route by which the story teller can influence things outside the nervous system. This inner part (yellow) represents everything we have experiences of (including both the outside world and our own bodies/emotions/thoughts/selves). The "I-function" in turn sits within the story teller. It is specifically those experiences we have of body/self, the "personal" aspect of the broader story.

Maybe (inverted postures again?) some visual images would be helpful at this point. As shown to the right, outside our nervous system is ... darkness. Inside the circle of our nervous system there are various degrees of light. Through interacting with the darkness (as well as via genetic transmission) our nervous systems acquire "tacit" knowledge; the grey circle includes all we know without knowing we know it (and without any experience of it). It is not only the basis for much of our action but the only source of information for the inner part of our nervous system, the story teller, and the only route by which the story teller can influence things outside the nervous system. This inner part (yellow) represents everything we have experiences of (including both the outside world and our own bodies/emotions/thoughts/selves). The "I-function" in turn sits within the story teller. It is specifically those experiences we have of body/self, the "personal" aspect of the broader story.

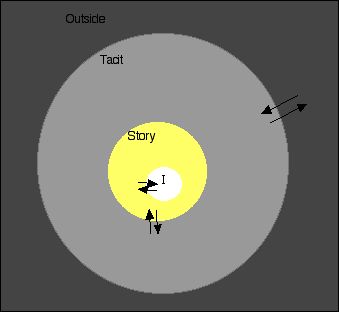

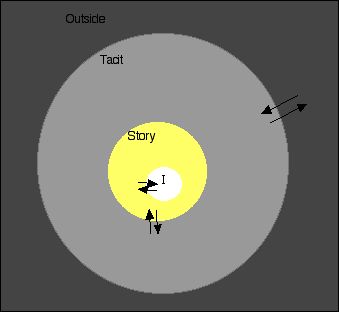

In the diagram to the right, the "I-function" is clearly "closer to the unconscious" in the sense that tacit knowledge is shown as going first to the "I-function" and only subsequently being distributed to the rest of the story teller. This would be a particularly simple way to account for the "I" as more immediate, more direct than other story telling features (those being fundamentally derivitive of the I-function). But its not the only way, and my intuitions say it is not the most likely one. So, a more general purpose version of the diagram below.

In this version, there are a variety of routes by which a variety of kinds of tacit knowledge reach the story teller and it is only after some further "story" type processing that things reach the "I-function". In this case, there is in the signal flow pathways no immediate explanation for the "I-function" being "closer to the unconscious". The notion of "closer to the unconscious" may nonetheless hold, for any of several other reasons. One is that the relative distance along processing pathways reaching the I-function is shorter than that for other story telling elements. Another is that there may be some distinctive and significant specialized features of tacit knowledge (including proprioceptive signals) that are delivered relatively directly to the I-function, in comparison to other parts of the story teller (Antonio Damasio, in The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness makes a strong case that this is in fact at least part of the explanation). A third is that the "self" element of story is, by its very nature, more ... personal, ie more expressive of tacit knowledge in a purer form, more about "a functioning unique being" (emphasis here mine), less subject to challenge from the outside.

In this version, there are a variety of routes by which a variety of kinds of tacit knowledge reach the story teller and it is only after some further "story" type processing that things reach the "I-function". In this case, there is in the signal flow pathways no immediate explanation for the "I-function" being "closer to the unconscious". The notion of "closer to the unconscious" may nonetheless hold, for any of several other reasons. One is that the relative distance along processing pathways reaching the I-function is shorter than that for other story telling elements. Another is that there may be some distinctive and significant specialized features of tacit knowledge (including proprioceptive signals) that are delivered relatively directly to the I-function, in comparison to other parts of the story teller (Antonio Damasio, in The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness makes a strong case that this is in fact at least part of the explanation). A third is that the "self" element of story is, by its very nature, more ... personal, ie more expressive of tacit knowledge in a purer form, more about "a functioning unique being" (emphasis here mine), less subject to challenge from the outside.

I won't try to adjudicate among these possibilities at the moment. For the present, my point is simply that neither the I-function nor the questions you're interested in disappear if one uses a basic tacit/story teller framework and, moreoever, that that framework provides a way to develop further lines of exploration that may help to shed additional light on questions that we're both interested in. How about that as a little tidying up? We keep the "I-function", situate it somewhere within the story teller, and go from there? I can already imagine some additional visual images in which we play with separate and intersecting signal paths related to the body, proprioception, and other things.

|

"Naked," "primitive," and "animal" all make sense in this framework as well, as long as one treats these as RELATIVE rather than absolute

|

"Naked," "primitive," and "animal" all make sense in this framework as well, as long as one treats these as RELATIVE rather than absolute: the I-function and its expressions are MORE naked, MORE primitive, MORE animal than some other aspects of story telling because they are closer to the unconscious. Though this doesn't grant them either absolute or uninterpreted status, it does allow one to distinguish, as you want to do, between a kind of art closer to the undressed body/self and art of more rarified/culturally sophisticated kinds. And to do so in a way that inverts more traditional judgements by making the primitive/animal foundational to the other kinds.

All of this bears as well on the matter of "survival". Yes, indeed, the "human animal still relies on its more primitive states to survive", precisely because the I-function, and the broader story teller of which it is a part depend on the unconscious as their primary reporter and analyzer of what is going on and as the substrate through which they have to work to do anything about it. The I-function may convince itself at times that survival depends on a favorable review of a museum show, a successful tenure decision, or the outcome of an arcane academic debate, but it is in fact sitting on the back of an unconscious that in general has much greater skill at and influence on survival.

Here too, though, one doesn't need or want to overstate the case. No, I don't think that "proprioception ... has mostly outworn its purpose for survival". It, and the unconscious, are a major part of whatever successes humans have as biological entities. On the flip side, though, being relatively more relatively more foundational doesn't mean that they are necessarily "wiser" in any given situation. Sometimes the less foundational acts of "thinking" are useful too. And part of what makes them useful is that they can in fact produce changes in what is more foundational ("I am, and I can think, therefore I can change who I am"). This is not actually a contradiction in terms. In biological systems, one frequently sees both "bottom up" and "top down" influences, so that things out of which other things are constructed are not fixed and invariant but rather themselves influenced by the constructions of which they are a part (cf From the Head to the Heart).

|

Its a short - and welcome -step from that to "moral questions" and "everything I mistrust about radical relativity even as I recognize that this sentence is true". And perhaps to ... "trauma"?

|

Its a short - and welcome -step from that to "moral questions" and "everything I mistrust about radical relativity even as I recognize that this sentence is true". And perhaps to ... "trauma"? I readily admit that I .... am less sympathetic to/moved by "trauma" than many people are, and not infrequently get into trouble on this score. I may here with you as well but ... we've built a bit of a platform so far by trusting each other and the only point is seeing what more we can do with it so ...

An easy (I hope) step first. I am indeed what I think you intend by the term "radical relativist." My path to that position, however, has been not the postmodernist/humanities route but rather one through science, biology, and neurobiology (mixed with a little existential philosophy and seasoned by growing up in the sixties). Perhaps for this reason, the notion that everything is a story is for me not a final position but a take off point for further inquiry. "IF one begins to have the feeling that there really ISN'T any such thing as "Truth" or "Reality" outside oneself, at least not a useful one that one can rely on as a fixed and stable motivator of and guide to one's own behavior, AND one has the feeling that PC/postmodernist solipsism (all stories are equally good) is not an adequate response to this feeling, THEN ...." (On Beyond Post-Modernism: Discriminating Stories) one needs to come up with a new and improved understanding of how to proceed.

I think that the tacit/story teller framework (with the I-function in it), combined with a sophisticated appreciation of evolution, gives us a promising opening for that improved understanding. Yes, a certain amount of stability is desirable at any given time. One needs a platform to take off from. On the flip side, "fluidity", I would argue is not only equally desirable to one degree or another but also ... inevitable. Humans may desire stability but they are, as biological entities, both products of and contributors to fluidity. Inevitably and unavoidably so.

All that you touch

You Change

All that you Change

Changes you

The only lasting truth

Is Change

...... Octavia Butler, Parable of the Sower

|

One can, as a story teller, either fight that or embrace it. To embrace it is not to become passive but rather to acknowledge/respect/even celebrate one's existence as a meaningful change agent. And to acknowledge/respect/encourage the same in others ("The rebel undoubtedly demands a certain degree of freedom for himself; but in no case, if he is consistent, does he demand the right to destroy the existence and freedom of others ... The freedom he claims, he claims for all ... He is not only the slave against the master, but also man against the world of master and slave" .... Albert Camus, The Rebel).

"Among the interesting features of this alternative is that it puts confidence in, rather than fears, having "nothing as definite" ... It puts confidence ... in individual judgements ("egos and desires") informed by, among other things, each individual's interconnections with other human beings. It says also that there is no "ultimate measure," but there is, in its place, the best one can do at any given time. Moreover, it treats "relativism" not as a "dictatorship" but rather as an invitation to individuals to be individuals, to discover and value both their commonalities and their differences. Finally, it offers a new sort of direction for humanity, one in which individuals themselves become for themselves (and each other) the active agents responsible for not being "carried here and there by the winds of doctrine", and one where everyone benefits from their own distinctive explorations and the ongoing and different explorations of others." ... Fundamentalism and Relativism: Finding a New Direction

|

It is precisely BECAUSE of the story telling feature ("nothing is definite"), and the existence on an "I-function" as a component of that (a story about onself and about one's relation to the world that is itself not definite) that we have the ability to conceive things (ourselves included) as other than we are at any given time.

|

It is precisely BECAUSE of the story telling feature ("nothing is definite"), and the existence on an "I-function" as a component of that (a story about onself and about one's relation to the world that is itself not definite) that we have the ability to conceive things (ourselves included) as other than we are at any given time. To conceive, and attempt to bring into existence, alternatives. To make art, science, and ... revolution. Some stories prove better than others at achieving this potential, and so not all stories are equal; there is a way to discriminate among them. Hence one need not fear story telling as either solipsistic or amoral. It is instead not only an inevitable feature of the human condition but one that gives us the wherewithal to conceive/critique/reconceive our selves, our cultures, and morality itself.

What about "radical relativity" and story telling for "someone who has had their world unseated, whose boundaries have been transgressed, whose sense of trust is gone, whose fear of the elements (tsunamies and hurricanes) is profound such that they cannot function ... [who] must have a story that s/he can share with others and believe?" There could indeed be a "problem of use" issue here, of "meaning derived in use", ie of context dependence. Perhaps "traumatic experience" makes someone sufficiently different from other humans so that story telling as radical relativity is at best irrelevant and at worst unsympathetic, even abusive?

"Trauma" is your area of expertise, not mine, but let's see if I can perhaps contribute to your thinking about it (as you've contributed to mine about the brain). My uninformed feeling is that traumatic experiences do not in fact put those having them into a separate category from other humans, that instead the experiences cause such people to be more aware than most of us are (or choose to be) of the deep nature of the human condition, one common to all of us. Many of us act much of the time as if there are reliable fixed points to our lives that we can rely on unquestioningly to give "meaning" to what we do. Could it be that it is the destruction of one or more of those fixed points that makes experiences "traumatic"? That people having such experiences are thereby forced to confront the human condition that there are in fact no fixed points that can be unquestioningly relied on, and that "meaning" is always story created for oneself out of whatever materials one has at hand?

|

an understanding of "radical relativity" and story telling might actually be therapeutic in dealing with trauma ... serve as well as some antidote to ... trauma ... lessen conflicts between humans and the associated traumas we cause each other

|

If so, an understanding of "radical relativity" and story telling might actually be therapeutic in dealing with trauma, a way to help people see themselves as creative agents rather than as irreparably damaged, and as meaningful participants in a broader human community rather than as people who have been by acts outside their control cut off from it. "Radical relativity" and story telling cannot of course prevent events like tsunamis and hurricanes but they might serve as well as some antidote to the resulting trauma (cf Continuity and Catastrophe and Meeting Death With a Cool Heart). And a more general understanding of and commitment to "radical relativity" and story telling could at least lessen conflicts between humans and the associated traumas we cause each other (cf 11 September 2001.

Phew. Not sure that actually "tidies up", but maybe it does explain why I think "story telling" is important? and give us a possible way to relate my "I-function" and your proprioception/body art to it? In a way that opens some directions for further conversation about .... survival, animal/being, trauma, whatever? The "I-function" is, thanks to your pushing, alive again (nestled in the bosom of the story teller). Hope this is all at least somewhat useful to your story as well.

Maybe (inverted postures again?) some visual images would be helpful at this point. As shown to the right, outside our nervous system is ... darkness. Inside the circle of our nervous system there are various degrees of light. Through interacting with the darkness (as well as via genetic transmission) our nervous systems acquire "tacit" knowledge; the grey circle includes all we know without knowing we know it (and without any experience of it). It is not only the basis for much of our action but the only source of information for the inner part of our nervous system, the story teller, and the only route by which the story teller can influence things outside the nervous system. This inner part (yellow) represents everything we have experiences of (including both the outside world and our own bodies/emotions/thoughts/selves). The "I-function" in turn sits within the story teller. It is specifically those experiences we have of body/self, the "personal" aspect of the broader story.

Maybe (inverted postures again?) some visual images would be helpful at this point. As shown to the right, outside our nervous system is ... darkness. Inside the circle of our nervous system there are various degrees of light. Through interacting with the darkness (as well as via genetic transmission) our nervous systems acquire "tacit" knowledge; the grey circle includes all we know without knowing we know it (and without any experience of it). It is not only the basis for much of our action but the only source of information for the inner part of our nervous system, the story teller, and the only route by which the story teller can influence things outside the nervous system. This inner part (yellow) represents everything we have experiences of (including both the outside world and our own bodies/emotions/thoughts/selves). The "I-function" in turn sits within the story teller. It is specifically those experiences we have of body/self, the "personal" aspect of the broader story.

In this version, there are a variety of routes by which a variety of kinds of tacit knowledge reach the story teller and it is only after some further "story" type processing that things reach the "I-function". In this case, there is in the signal flow pathways no immediate explanation for the "I-function" being "closer to the unconscious". The notion of "closer to the unconscious" may nonetheless hold, for any of several other reasons. One is that the relative distance along processing pathways reaching the I-function is shorter than that for other story telling elements. Another is that there may be some distinctive and significant specialized features of tacit knowledge (including proprioceptive signals) that are delivered relatively directly to the I-function, in comparison to other parts of the story teller (Antonio Damasio, in The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness makes a strong case that this is in fact at least part of the explanation). A third is that the "self" element of story is, by its very nature, more ... personal, ie more expressive of tacit knowledge in a purer form, more about "a functioning unique being" (emphasis here mine), less subject to challenge from the outside.

In this version, there are a variety of routes by which a variety of kinds of tacit knowledge reach the story teller and it is only after some further "story" type processing that things reach the "I-function". In this case, there is in the signal flow pathways no immediate explanation for the "I-function" being "closer to the unconscious". The notion of "closer to the unconscious" may nonetheless hold, for any of several other reasons. One is that the relative distance along processing pathways reaching the I-function is shorter than that for other story telling elements. Another is that there may be some distinctive and significant specialized features of tacit knowledge (including proprioceptive signals) that are delivered relatively directly to the I-function, in comparison to other parts of the story teller (Antonio Damasio, in The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness makes a strong case that this is in fact at least part of the explanation). A third is that the "self" element of story is, by its very nature, more ... personal, ie more expressive of tacit knowledge in a purer form, more about "a functioning unique being" (emphasis here mine), less subject to challenge from the outside.