Eveline Stang, College Seminar (December 2001)

| The following is a working draft of an article which the authors have submitted for publication. It reflects their experience teaching in the College Seminar Program at Bryn Mawr College, and is made available on Serendip as a contribution to continuing discussion of the nature of liberal arts education, with a particular focus on the significance of writing in the process.Your reactions and comments are welcome. |

Anne Dalke (English, Feminist and Gender Studies)

Paul Grobstein (Biology, Center for Science in Society)

Bryn Mawr College

For Sharon and Hayley (collaborators, provocateurs)

|

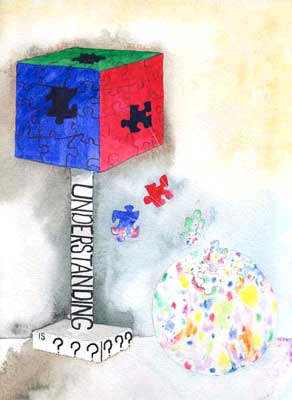

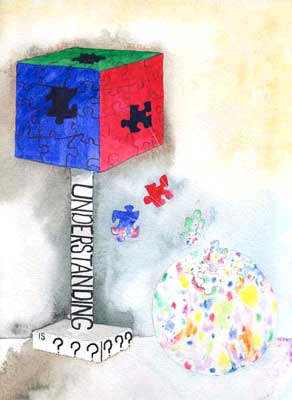

A few months ago my impressions [of this image] were: "The cube seems to suggest linear thinking, i.e. logic and reason. The ball suggests something whole or complete (intuitive knowledge?) perhaps the missing puzzle pieces of logic must become painted with the various shades of intuitive knowledge . . . perhaps the cube will eventually become the ball!". . . . At the beginning of the term, I resisted the "cube of applied logic," secretly favoring the multi-colored "sphere of intuitive knowledge." (The resistance should have been a clue: in my experience it usually means the avoidance of learning something!) The bold colors of logic and critical thinking suggested limitation, and a lack of mental "freedom." Reasoning represented an often cumbersome, painful process requiring patience and discipline. . . Gradually I found that the exploration of various models of thinking could be interesting and even exciting. I discovered that intuitive thinkers like myself need not fear theoretical models of applied logic. Theoretical models are simply different glasses through which to observe and interpret the world. While I have been busy learning to "think" in new ways, it seems that I have been revising my attitude towards thinking, as well. I have learned that exploring new models or frameworks encourages a certain fluidity of thinking and keeps the mind reaching for new understandings.

Eveline Stang, College Seminar (December 2001) |

|

The story we want to tell here arose in part deliberatively, in the context of Bryn Mawr's interdisciplinary writing-intensive College Seminar Program, but also in part serendipitously, without our conscious intent. An important aspect of our story is that genuine exploration occurs only in the absence of fully defined objectives. One of our aims here is to make concrete our conception of the fundamental role of risk-taking both in curricular design and in its enactment in the classroom.

For the past several semesters of teaching, we have ourselves been discovering a generative way of understanding how our brains work, of conceptualizing thinking in a broad context of living, and of encouraging the sort of writing which might most effectively both express and contribute to such activities. Presuming that differences are productive, without knowing in advance exactly what will emerge from their interaction is--we'll also attempt to illustrate--necessary not only among faculty in the conception of a course but also between faculty and students as the course plays itself out. Risk-taking is essential, but so too is a structure of trust and community that supports its generativity. It is gratifying when a student notices the objectives that evolve and can be achieved what can occur in such an environment: "a certain fluidity of thinking" that "keeps the mind reaching for new understandings."

Our account of how we came to move in this direction, and our invitation to other educators to do the same, draws on our creation and elaboration of a course, on our students' experiences in taking the course with us, and on the reflections of us all on what happened among us. This essay is a "braid" explaining the merits of a braid: it weaves together the language of students and of teachers, of science and of literary analysis, in articulating a principal theme: the importance of activating and engaging, in an open-ended way, three isolatable but interdependent "loops."

As illustrated in the figure below, the first and most basic of these loops (A) is a sensory-motor and largely unconscious "inside-outside" exchange: the experiential process of learning by acting in the world and being altered by the consequences of doing so. The second loop (B) is self-reflective: an internal "intuitive-analytic" process that reciprocally links the tacit understandings of the first exchange with an explicit process of trying to make sense of them. The third loop (C) is an "interpersonal" one in which both explicit and tacit understandings are conveyed between individuals.

The operation of the three loops begins, both in course design and in the classroom, with experiences and intuitions in the unconscious; involves the more or less self-conscious act of making explicit those intuitions (B); and continues with the testing of such explicit formulations, both privately (A) and publicly (C), thus activating a complex and continuous feedback cycle in which new intuitions arise, unconscious skills are revised by conscious reflection, and new experiences are generated.

Each loop functions to some degree independently and makes, in its own right, a significant contribution to the learning process. The two terms being exchanged in each loop represent different "stories," with the reciprocal and somewhat unpredictable potential of altering one other. The three loops also intersect with one another in unpredictable ways, so that activity in any one influences the others; both "fluidity of thinking" and "reaching for new understandings" are amplified by this larger braided structure.

This process began, in our case, with an interpersonal loop that increased our awareness of the significance of additional exchanges. Accordingly, we begin our story with an account of the generativity of the interpersonal loop, then add the experiential and internal ones, before reflecting on the endlessness of their braiding. We close with some thoughts on the larger intellectual and social implications of what we believe we have learned through our recent experiences as educators.

I. The Interpersonal Loop: Designing a Course Together

|

The clashing point of two subjects, two disciplines, two cultures--of two galaxies, so far as that goes--ought to produce creative chances.

C.P. Snow, The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution (1959) But it was from the difference between us, not from the affinities and likenesses, but from the difference, that [understanding] came: and it was itself the bridge, the only bridge, across what divided us.

Ursula LeGuin, The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) |

While both of us are experienced teachers, and had each taught previously in the first-year seminar program, we had not taught together and came to the enterprise from quite different directions. One of us is a woman and literary scholar with particular interests in Quakerism, feminism and nineteenth-century American literature. The other is a man, a biologist and an atheist whose focus has been on neurobiology, human behavior and philosophy of science. Our differing backgrounds created a number of discordances. Each of us was differently familiar with, and differently engaged by, the humanities and the sciences, with associated different conceptions of the academic and human enterprise, as well as very different understandings both of our formal course objectives and of the degree of direction our seminar might require. She was inclined to the particular, he to the abstract. She preferred the well-written novel, he the straightforward essay. He rooted understanding in personal experience, she in collective story. She was uncomfortable with the idea of "progress," he presumed it.

Our differences were such that colleagues doubted we could conceive together a common syllabus, much less collaborate on a successful course. We shared, however, a common dissatisfaction with "things as they are," an associated inclination to try out new approaches, and a conviction that the differences between us represented more promise than problem. It was not just our differences, but a particular combination of differences and likenesses that led to our productive collaboration. Although we were unaware of it at the time, the back-and-forthing between us in developing a syllabus was our first intimation of the importance of loopiness: an iterative, not linear, exchange of what lay inside and outside, of the intuitive and analytic, the experiential and academic.

A commitment to the generative potential of bringing together faculty with different backgrounds and investments is central to the College Seminar Program, and we regard our own experience as a testimonial to the appropriateness of that venture-while broadening the scope of its underlying logic. The generativity of our interactions suggests to us that an optimal educational environment should facilitate comparable interactions between faculty and students, as well as among students themselves, interactions based on similarity AND difference.

In discussions with colleagues from a range of disciplines (see The Two Cultures ), we discovered three starting points for bridging our field-specific disparities:

Language is used quite differently in different contexts, ranging from science, where it is intended to be quite precise; through day-to-day exchange, where it is used to communicate and elicit information; to literature, where it is intentionally ambiguous, playful, and inviting of engaged interpretation.

While most of the work we do in college classrooms both originates in and is evaluated in terms of deliberative language use, in which focus and precision are the desired characteristics, much creative work is not carried out in these terms. Most of the ongoing acquisition of new understandings occurs rather by acting and observing its consequences, or by observing the actions of, and their consequences for, others. Such creations (enacted, for example, by dancers, painters, and scientists gathering observations) draw largely on tacit understanding and are not readily (perhaps never completely) describable in language.

Both of us valued experiential learning (although for different reasons: she drew on her experiences as a Quaker, he on his as a scientist). Because both of us were also convinced that the academic enterprise generally emphasizes explicit, language-based, descriptive exploration at the cost of implicit, action-based engagement, we agreed on the need to find ways of effectively blending, rather than opposing, the two activities in an introductory college-level writing-and-thinking course. The guiding concept of our planning was our awareness that understanding involves a continual cyclic interaction between knowledge acquired largely unconsciously through action, and critical synthetic processes that are mostly conscious. The latter actively interrogate implicit understanding, both altering it in individuals and making it more accessible to the public, collective intellectual enterprise.

Valorizing understanding at the explicit, language-based level neglects the fundamental importance of the implicit, action part of the cycle, disadvantaging those having distinctive strengths in this area. Doing so may well underlie the frustration of some faculty both with their own intellectual activities and in their experiences with students. Our insistence on highlighting the fundamental bi-partite structure of understanding, the way the brain is designed by evolution to work, is consistent with observations from neurobiology and cognitive science (cf. Damasio, Dennett, Norretranders, Grobstein 2002, Grobstein 2001b). It also accords with the recognition by feminist educators that interactive dialogic teaching modes are frequently the most effective ones (cf. Belenky, Goldberger, Dalke).

The ambitious decision to expand this first-year "writing course" to include multiple interactive levels of understanding meant that we wanted our students not just to use language well, but to do so as a record and reaction to acting and being acted upon. Ours was a course not only in writing in a collegiate style, but also a course to develop credible content to write about. This in turn implied that we should help our students see writing as action and response.

The "interpersonal loop" we trace above went well beyond our own interactions; it included those we had with our students, as well as interactions among the students themselves, who understood, appreciated and articulated the dynamic. As Marie-Laure Epaminondas observed, "In the class everybody else was listening to what I had to say. . . . It was because of everybody's else's energy that I was able to bring new ideas to the table." Zoe Anspacher elaborated:

| I use the group meeting as an extension of my mind. When I participate I am inside a bigger brain and my brain is just a neuron, sending and receiving signals from other neurons, the brains of my classmates . . . . One day [when] I try to speak about the reading . . . I am having trouble connecting the ideas I have jotted on the page with the ideas I am hearing and the new idea I have at the moment. The bigger brain helps me . . . . |

To facilitate this process, we made extensive use of on-line forums and web-publication of student papers. We asserted that "students" were also teachers and that student work was not simply an exercise to be evaluated by teachers but rather was also an important contribution to the education of all.

We also turned our attention to the creative spaces lurking above, below and around the spectrum of languages available to us, focusing as much on activities of observation, experimentation and exploration as on languages of distillation.

II. "Original Seeking": Adding the Experiential Loop

| Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion of revelation to us, and not to the history of theirs? |

We began designing our course by choosing as our logo the image which prefaces this essay; it was painted by Sharon Burgmayer, a colleague in the Bryn Mawr College Chemistry Department. (See her video describing the creation of the image: Understanding's Birth). At our first class gathering we invited our students to describe what they saw when they looked at Sharon Burgmayer's image. In doing so, we were drawing both on Janna Stern's use of visual images as a way to explore differences between, and promote interpersonal understanding among, individual viewers (see Measure for Measure), and on the advice of a colleague in the English Department, Katherine Rowe, who had suggested to us the value of using visual images in the classroom. Students have immediate responses to images, and so find themselves more easily able to "read" them--a reading that the rest of the class can complicate and build on (another example of the interpersonal loop in action among students). It is important, in the classroom, to use not only texts (understandings of others expressed in language) but also the kinds of direct, less mediated experiences that are provided by interactions with other kinds of material. We asked our students to be aware of how texts and images affected them-moved them to engagement or detachment-and then to examine and attempt to explain the source of such perceptions.

The opening gesture of the course became a model for much of what followed. In addition to using images and performances, we also sent students out of the classroom to collect observations themselves, rather than having all of their thinking based on the renditions of others who had gone before. Our decision to highlight the work of personal observation was in part the result of Paul's experience in an earlier College Seminar, where students had expressed the strong, nearly uniform opinion that unfaithfulness was more characteristic of males than females. When Paul asked, however, what they "knew personally," a substantial number of the students reported knowing more unfaithful females. Why did they believe things that contradicted what they knew experientially? Several students offered an explicit answer: their experiences are always limited. What they hear from others reflects a broader range of awareness, and so is more likely correct than what they experience themselves. A reasonable story, but . . . one that leaves out important tools of understanding.

The tension between individual experience and collective stories is an important one in a variety of realms, including the scientific and the theological. Our intent was not to come down on one side of the dichotomy, but rather to identify both components in a generative interaction. The texts in our course included several works on that theme, including Bertolt Brecht's Galileo and Edwin Abbott's Flatland. We read and discussed the implications of such books; we also had our students make observations in relation to questions and hypotheses of their own. They learned thereby how knowledge results not just from hearing, reading and interpreting written texts, but also from making personal observations-which they did casually and naturally anyway. Surprisingly and satisfyingly, this process gave us a way to teach both "humanities" and "science" as the formalization of a process of inferring from direct experience. What we call "analytic thinking" is simply a more systematic engagement in that process, which we insisted our students repeat throughout the semester, as they learned to observe, read and write with a sense of engagement and investment in the outcome of the process.

Such directions accord with the increasing recognition by educators that hands-on, exploratory, interactive teaching modes are effective in pre-college classrooms. Over a hundred years ago, John Dewey traced his "pedagogic creed": "that education must be conceived as a continuing reconstruction of experience, that the process and the goal of education are the same thing" (n.p.) Our College Seminar students developed an improved awareness of what science is (how to practice it, by collecting observations and organizing them into an account that makes sense of their relationship) and a recognition that this process goes on naturally, inevitably and continually within each of us all the time. By inviting them into this process of spontaneous, then increasingly reflective description, we were enacting the bi-directional quality of the "experiential loop." This was to become part of the guiding intellectual trajectory, and one of the primary motivators, of the work we were doing together: the reciprocal interplay between our own stories and those of the world surrounding us.

Every other week, as we asked our students to "read" another of Sharon Burgmayer's paintings, we were re-activating the experiential loop that was paradigmatic for their work in the course. We also continually harkened back to the interpersonal loop: recording their stories on-line meant that they were listening to those of one another, and so came to revise them in the light of the stories of others. In the process, the artist herself came to revise her appreciation of what she had painted. At semester's end, Sharon Burgmayer wrote to our students about the evolution of her own understanding of what "Understanding Is":

| In the original story, I "saw" the pieces moving in one direction only. . . . You . . . have told . . . stories that have multiplied the dimensions of "understanding" that can be extracted from it. From these stories I, too, now appreciate the ambiguity of pieces moving in both directions. |

Activating the experiential and interpersonal loops was not, however, the whole story. There was an important step between having experiences and the kinds of additional creativity that depend on being aware of how one is making sense of those experiences. This is the third loop, moving between intuitive and analytical aspects of thinking, to which we now turn our attention.

III. Telling Stories To Oneself: Recognizing the Internal Loop

|

We know more than we can tell and we can know nothing without

relying upon those things which we may not be able to tell.

Michael Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension (1967) Everyone in the class taught me things . . . I desperately needed to learn. For a few examples:

Chelsea Phillips, College Seminar (December 2001)

|

Both the interpersonal and the experiential loops are familiar to most educators, and have been attended to in pedagogical considerations in a variety of contexts. We are arguing here that they work best not only in interaction with one another, but with a third loop that deserves more explicit attention: an internal exchange between tacit (unconscious) and explicit (conscious) understandings. That many students find it easier to respond to images than to text is, we suspect, one indication of the importance and function of this exchange between intuitive and analytic knowledge.

It is by now well accepted in Composition Studies that the process of writing can productively be conceptualized in two stages: an earlier spontaneous brainstorming step and the later process of organizing and editing what one has to say (cf. Berthoff, Bizzell, Flower and Hayes, Lindemann). The loop we describe relates to this recognition of a distinction between brainstorming and editing, but we wish to emphasize that the underlying phenomena are not specific to the act of writing. Brainstorming and editing are specific instances of a much more general two-component loop within the brain. The intuitive and the analytic each draw from and feed one another in a continuing cyclic pattern, which parallels both the interactions between inside and outside, and between individual and social.

The writing assignments in our course refused the hierarchy which privileges brainstorming over editing, as well as the linearity of that sequence. We insisted instead on a continuously running feedback loop, moving back and forth between the expansive generativity of unconscious work and the focused precision of conscious reflection. The process of "squeezing down" what one has experienced into the form of a story is the analytic part. It in turn means the creation of something new, which invites further elaboration. The process inevitably creates the desire to "fill in the gaps," invites the invention of new stories to say what it does not say, from points of view it has failed to represent. From both those impulses, further expansion and further compression-in the form of new stories-always emerges.

We included in our course several texts that explored explicitly the ways in which what we know unconsciously affects both our storytelling and our interpretation of stories (see Vygotsky, Polanyi, Sacks). Exploring together our own funds of implicit knowledge and the possibility of making them explicit, we traced the interacting loop of internal understanding: defining the concept of tacit understanding, then positing its conscious interrogation and eventual revision. The sequential claims of this portion of the course were that

In exploring this form of coming-to-knowledge, we asked our students to describe their own experiences of implicit understanding. What tacit knowledge had they come into the classroom already possessing? What did they know that they could not tell? (And? So? How were they going to tell it?). What body knowledge (of knitting, or chopping vegetables, or piano playing or walking) did they possess, without ever having it articulated for or by themselves? How could they observe that, how articulate it, how alter it?

As we concluded the portion of the course focused on implicit knowledge, we paused to reflect on a novel: The first year, we read the story of Beloved, in which Toni Morrison, though a process of exhaustive revision, used the language of tacit knowing to represent the structure of the unconscious (one which makes no distinction, for instance, between what is "real" and what is "imaginary"). In the second year, we invited Octavia Butler to visit campus. We read her Parable of the Sower, in which the protagonist recognizes the exhaustion of old stories due to the limitations of the tacit understandings on which they are based, and sets about writing a new one, before being provoked, by its failure in turn, to revise both what she has written and lived by.

Writing a narrative structures knowledge so we can learn it; revising narrative re-structures it so we can change it. This essay itself is something of a meta-narrative: we exercise our theory in order to explain it, structure our knowledge, making it accessible and thereby re-structurable.

We started this process in our class by inviting our students to tell stories about ourselves, moved out to construct stories about the nature of the physical world, moved in to accounts of the brain's tacit processes, then out again to cultural stories. We ended the course by re-viewing old stories about a place that was insistently real to us all-the place called Bryn Mawr-and then trying to imagine it differently. We drew on Ray McDermott and Herve Vareene's essay, "Culture as Disability," for its excellent illustration of the ways in which the set of abilities valued by any given culture generates a concomitant structure of disabilities. Asking our students first to identify what was disabling about Bryn Mawr, we then invited them to conceive of new stories about the College, thereby revising the story that we are all constructing here together.

IV.The Endless Loop: A Process of Eternal Revision

|

for me, the box (colored so brightly, brightly and w/ beauty; i revel in the intensity of these primary colors) clearly represents academic "knowledge," the sort of "packaging" that shows up as disciplines like "biology" or "literary studies" or "anthropology," while the globe is the multiple pleasing richnesses of the world. but i really don't like the way this artist has figured the relationship between these two images. rather than "reading" what she's drawn, i'd prefer to re-draw the picture/re-arrange the interaction between the parts. i'd get rid of the stand and its label, put the box and the globe on the same level, let the puzzle pieces flow back and forth between them, in order to "say" that the rich

multiplicity of the world is what feeds our academic "packages," but the sense those packages make of the world has the capacity for re-shaping it in turn-and on and on/round and round/back and forth it goes. (in the picture, as it's currently drawn, gravity works against that back-and-forth process). now: WOULDN'T i just like it a LOT if, before class ends in december, each of us could not just describe (as i just have), but actually DRAW our own figure of what "understanding" looks like.

Anne Dalke, Bryn Mawr, College Seminar (September 2001) |

The process of endlessly telling and revising stories, in the attempt to take account of new observations generated by the old ones, proved to be the central concept of our course. We invited our students to engage with us in an ever-renewable and renewing process of making sense of the world, beginning with gathering experience and information; recording it-oft times not knowing what we meant; then further articulating and shaping it into the form of a story about it, a form which often drew on those of known old stories. Those stories always turned out to be incomplete and revisable in light of new information and knowledge. And so the cycle continued, as we asked, again and again, whether conventional myths and stories were adequate to what we knew, had experienced, were learning; as we asked what new forms might accommodate new information, what new stories might thus be generated.

We framed our asking in the form of a sequence of five assignments, each re-written several times, each intended to place what our students knew experimentally into conversation with something they may not have known or encountered before. The process was a difficult one, involving a complicated push-and-pull of authority and humility, as we asked the students both to claim what they knew and to acknowledge what they didn't yet know, and to stretch to figure out the relation between the two. That stretch was facilitated by our own willingness and commitment to "get it less wrong" ( Grobstein 1993), as well as by our acknowledgement that trust is essential in the process of continual stretching. The process involved, always, moving back and forth between intuition and intentionality, between spontaneous narrative and reflection on it; more centrally, it involved recognizing the relation between the two, and shaping and re-shaping essays to acknowledge the movement.

Through this range of assignments, we came to agree that the best stories, in science as in literature, are those which both make sense of past observations and invite and enable further work: they are the stories which explain the most data, and which are also open-ended, productive both of change and further stories. As the semesters moved along, our definition of "story" became increasingly pointed, increasingly congruent with what might more familiarly be called "theory": that is, as a construction which is potentially disprovable and falsifiable. With that understanding came the acknowledgement that it is not just imaginable but essential that observations can show any story to be wrong, that no final proof is possible, in science as in literature.

There are, of course, pros and cons to this story of "story." It refuses the comfortable distinction with which many of our students started the course: that there is an obvious difference between stories and reality. (After repeatedly encountering "story" in a variety of different contexts, a number of our students began to express the feeling that they "never wanted to hear the word again!") On the other hand, the idea of story as continually and endlessly revisable was empowering to many of them, providing an experience of the academic enterprise in which, rather than passive consumers, they were already active participants (an identity encouraged by-among other things-the web-publication of their thoughts and essays). A course that embodies continual inquiry rather than achievement of mastery in some area is, arguably, both a better representation of intellectual work and better preparation for participation in it. One has to learn sometime that there is no "right" but only the process of "getting it less wrong," and we saw no reason why it should be later rather than sooner.

V. Interrogating the Text/Enacting the Performance: Braiding the Loops

|

People learn through action and reflection, dialogue and silence, collaboration and struggle. Faculty members also recognize that different people learn in different ways, and professors strive to tap students' multiple intelligences by including visual, musical, dramatic, and other forms of exploration and expression to structure, extend, and enrich students' inquiry and equip them to do the same with those they serve.

Philosophy of the Education Program, Bryn Mawr College and Haverford College (2003) In trying to satisfy my curiosity it has been a thrill to discover new ideas. At first those ideas and concepts were not known to anyone, not even myself, until my own little voice finally announced the colors of those ideas. Sometimes it has sounded like a song . . . . In this class, all of my senses were called into consciousness . . . . Play-acting also played a important role for experience in ideas and concepts. For example, when I needed to express my own ideas and concepts about tacit knowledge I brought words to consciousness by creating a skit . . . . I could experience these new ideas and concepts through body movement and facial gesture. This was a complementary step that had been primordial for a language learner like myself . . . . In this class my life of learning became meaningful. I learned more than I could really handle.

Marie-Laure Epaminondas, College Seminar (December 2001) |

Performance provides a nice illustration of the interaction of all three loops. By making use of both language and bodily movement, it simultaneously provides experience and reflection on it, activates conscious and unconscious processes, and is fundamentally interpersonal, both in conception and in its engagement with an audience.

We hosted several performative evenings during the course of each semester. In an attempt to show our students that tacit knowledge was manipulatable- that, once made explicit, it does not cease to be tacit, but can be "fed back" into the unconscious, and so altered-we required them to enact such a change with their bodies. In asking all of them to become performers, not just interpretively engaged but physically committed to acting out their perceptions, we were working in concert with one of our colleagues, Linda Caruso-Haviland, who directs the Dance Program at Bryn Mawr.

Linda Haviland has spoken cogently and frequently about the multiple ways in which "as a woman and a dancer" she has long been "removed as any sort of valid epistemic subject" from academic culture. Her work, like ours, re-conceptualizes all of us learners as operating in a more bi-directional and interactive state than is usual in the academy. We put our students through a series of exercises, asking them to be creative and intuitive enough to project what they knew into three dimensions, to experience the profundity of bodily experience. This sort of movement invited in "bodied ways of knowing," providing our students with mechanisms, distinct from discussion, for articulating what they knew unconsciously. Analysis and further understanding arose from such experiments and experiences.

Working simultaneously with three intersecting loops increases the unpredictability and risk of this whole enterprise. In particular, inviting our students into the playground that is the unconscious-moreover, inviting them to renovate that space (or at least to consider the possibility of doing so)-can be tricky work, either dismissed as trivial and ineffective, or treated suspiciously as intrusive and dangerous. ("Learning more than one can really handle" is a lot to ask of a first-year college student. As another student said, "I seem incapable of in-dwelling. Nothing touches me on the inside . . . Feelings are a hindrance. It is easy to succeed if you do not feel.")

The advantages and hazards of this unpredictability were strikingly illustrated by one performative evening and its aftermath. In preparation for a "Symposium on Fairy Tales," we had read a selection of fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm, followed by Anne Sexton's dark Transformations of those stories. One group of students decided to perform several related skits, describing first a story of learning, then repeating it in fairy tale form and finally in more disturbing Sexton-like mode. These iterative tales, which culminated in the science fiction saga of Princess Krispie, assaulted by aliens and saved by a prince who later assaults her in turn, traced how a certain rice krispie treat had come, over the past several weeks, to be sitting on the classroom table. (The tales elaborated on this theme largely because the consumption of food in Sexton's poetry had such strong sexual overtones.)

At the end of performance, the actors distributed rice krispie treats to the other students in the course, some of whom were non-traditional students, older women returning to college in our McBride Scholars Program. Most members of the audience ate them immediately, but what one McBride called the "dark musings on mayhem" began to appear on our on-line course forum the next day. Ro. Finn was the first to raise some questions about what had happened among us:

| Maybe it was the Rocky Horror Show touch (connecting with the audience by handing out sweet little things at the end), that kept me thinking about this story . . . half way through it . . . I was wondering if any of the writers/actors had experienced any of what they were delivering . . . or known anyone who had. What was the message? |

When one of the actors, Rachel Steinberg, reported that "our intention in giving out the treats at the end was for people to question eating them, and to feel dirty about eating them," Ro. Finn responded, "That is, reportedly, how the victim of such a crime feels, but not the perpetrator. Did you mean for us all to identify with the victims? And, if so, what would we be/feel if we ate one of the treats at the end?"

Ro. Finn's queries led to others. Another McBride, Margaret Ketchersid, also found herself re-thinking what she had been shown, and how she herself had initially reacted to the performance:

| I was not disturbed at first about the Krispie story-I thought it was highly entertaining . . . . After reading Ro.'s original post I reflected a little more and began to feel uneasy . . . . It's a little scary to think about a group of women (and by this I mean all of us who were there) laughing about the rape and degradation of women. For myself, I'm disgusted not only that I laughed at the time and didn't immediately see anything disturbing enough to bring up at the meeting, but also that while driving home, when it came up in my mind I just pushed it away. |

It is significant that the initial and most insistent follow-up questions about the meaning of this performance came from the older generation of students, who had themselves agreed not to perform at the symposium one of their own stories about sexual abuse. As Diane Gibfried observed,

| feeling the consequences of "not" doing it was also uncomfortable. The silence was deafening. "Does Sleeping Beauty still sleep?" . . . it seems that she does. Was this censorship? . . . did this mean that it should not be told? . . . where do we stand then, with the three monkeys with their hands over their ears, eyes and mouths? There had to be a way to speak the truth which this woman courageously presented to us. . . .Do we need to be seduced by allegory in order to accept truths that are too difficult for us to grasp? Or too easy for us to deny? |

A number of the younger students were taken aback by the reactions of the older generation. Claire Mahler's response was characteristic:

| Goodness. I am entirely surprised and impressed by the controversy over the rice krispie treat presentation from Sunday evening . . . . I can verify that our purpose with the story was indeed to "gross people out" when we passed out the treats at the end. We were going for that shock value, not really thinking about the story itself in depth. The culmination of various ideas quickly thrown out created our tale. . . .However. . . . It makes me feel ill to think that we have been socialized to completely ignore the atrocities and the implications thereof and use events such as rape simply to play around. . . . As you can probably tell, I myself am still trying to figure out in my own mind what an acceptable balance would be (if one can be found . . . ) |

Other actors, like Joy Woffindin, also found that they had learned from the exchange:

| I think the "controversy" (if it can be called that) over the tale of Princess Krispie has been an amazing example of how the audience/reader can get something from a story that the author didn't intend (or didn't THINK he/she intended) . . . . The most interesting part of all this to me however, is that now I have gone back and thought to myself: maybe I did mean something deeper when I wrote the poem. |

All three of the loops that our course intended to foreground intersected in this edgy exchange. The students had the experience of direct engagement with the performance; they moved from the spontaneous playfulness of the unconscious into the more reflective work of the conscious mind and back again; when they exchanged their experiences with one another on-line, they came to revise their understandings of the whole.

The last exchange, in particular, made it clear how much we all need one another, precisely because we do see the world differently: the older ones needed the perspective of those who were younger, and the younger ones needed the reflections of those who had lived longer. And then we all needed to loop back again and again into more-and now altered-understanding. Doing so involved an insistently social dynamic.

This kind of social process inevitably risks discomfort, but also supports the kind of playfulness that allows productive examination of that which most troubles us. As Hayley Thomas, a folklorist who co-taught the seminar with us, observed,

| it wasn't like any other fairy tale conference I've ever attended. . . . But I recognize it. I recognize its ludic energy, the deep and playful space generated when folks get together to give body and voice to the traditional narratives we tell and thus re-vise in the telling. I recognize the break/through into performance. In carnivalesque moments, like our conference, we simultaneously consent to identify with and be estranged from our everyday selves for the sake of play, knowledge, revolution, and/ or dialogue. Laughing and squirming at things we don't dare invite out loud into our day to day, at least not without some frame, often humor, to help soothe and heal. The therapy tale, the Princess Trilogy, all of the stories spoken and performed, tugged at me, signaling to me that something significant was happening for me, in me, in and through language. They tore laughter from me, but also ripped at other things in me, I admit. That's the way of humor. It's an optimistic process of delicately matching scraps of sense and nonsense and it's always risky, uncomfortable, and ambiguous. Think that's one reason why the resolution for a joke is called a punch line? |

There were perhaps other downsides of the game into which we had invited our students. The loopy discipline of the course was very explicitly articulated, for instance, and the cost of this organization, of its decidedly directed arc was, of course, numerous other possible trajectories we did not explore. One of the students observed, for instance, that the "agenda for discussions seemed restricting." "What's with the skits??" asked another in her final evaluation. A third observed, "the skits/demonstrations . . . I would caution about. Some classmates felt them to be superfluous. . . . I felt that our . . . joint seminar wasn't very enriching. We didn't get to the point or uncover new meaning."

It is perhaps an inevitable character of curricular experimentation that particular innovations work better for some students than for others. We may have been too facile in bringing texts together into a "package," losing the integrity of things in themselves, and the multiple possibilities they might invoke. Did the course still valorize conventional academic methods of focused understanding?

Our students also lamented that we had not given them adequate time for struggling through this material. Of course there are worse complaints to be handed at the end of a semester, but this one does suggest a disability of the sort of playfulness in which we were engaged: our refusal to linger too long in any one place, as we turned always to new, and ever larger, sites of exploration. (The Princess Krispie event, for instance, had many other layers than those reported and explored here. Why was she called "Princess" Krispie, given a title that connotes a member of the elite with no power?) Perhaps this too is a valuable reminder of the diversity of student needs, and of the inevitability, in pedagogical experimentation, of getting it never right, but only, and always, less wrong.

V. Reflections on the Implications: Transcending the Two Cultures

| I believe the intellectual life of the whole of western society is increasingly being split into two polar groups. When I say the intellectual life, I mean to include also a large part of our practical life, because I should be the last person to suggest the two can be at the deepest level be distinguished. Literary intellectuals at one pole-at the other scientists. Between the two a gulf of mutual incomprehension-

sometimes hostility and dislike, but most of all lack of understanding . . . . This polarisation is sheer loss to us all. To us as people, and to our society. It is at the same time practical and intellectual and creative loss, and I repeat that it is false to imagine that those three considerations are clearly separable.

C.P. Snow, The Two Cultures (1959) |

We ended each semester of teaching with an enormous appreciation of both the pleasure and the productivity of engaging in three interrelated feedback loops with our students. We end this account of the usefulness of this sort of teaching, thinking and writing, however, with a much larger claim: that in inviting our students and ourselves into the self-reflective and braided process of moving back and forth between self and world, the self's unconscious and conscious understanding, and different stories told by different selves, we are making a substantial contribution to the long-overdue breakdown of a two-cultures divide first identified by C.P. Snow over fifty years ago-as well as that of a range of associated binaries which he did not describe.

Snow's analysis of the "two cultures" was motivated by what he saw as a "mutual incomprehension, sometimes hostility and dislike, but most of all lack of understanding" between two groups of humans. Snow identified the two groups as humanists and scientists, but we have come to think that one might equally identify them as women and men, as conservatives and radicals, or as believers and atheists. The commonality, we suggest, is a contrast between two styles of making sense of the world, one broader and more intuitive, the other focused and more analytic. Associated with this difference in style is a difference in attitude toward "progress." On the one hand, there is a desire to leave nothing out, to conserve all there is, and hence a skepticism about the meaning and significance of change. On the other, there is an inclination to move on, to see the past as preparation for the future, and an optimism that change is, in some sense, improvement.

We understand these binaries to have their origin in the bi-partite character of the brain, and so as inherent in each of us. Moreover, the continual production and resolution of the binaries is reflected in the brain. Each of us begins with a largely unconscious experience of the world. We move from the full, unstructured business of the unconscious into the more spare and structured work of the conscious mind: generating a story, squeezing experience down into a shape which of necessity leaves out some aspect of what has occurred-and so generates yet another story, yet another "reduction" that is productive of further storytelling. Back and forth we go, between an unconscious that deals with the word in terms of rich interconnections, and a conscious that treats it in terms of objects and explanations, each feeding, inciting, and altering the other through their differences (cf. Dalke, Grobstein, McCormack).

It is precisely the differences in style between the two parts of the brain, and the continual effort to find ways to reconcile their resulting stories, that is responsible for the permanent tension that generates creative activity. This is the core of our always-evolving "solution" to the problem of binaries, wherever we find them: insisting on the loopiness of moving constantly back and forth between different stories, not only different stories within oneself, but also the different stories told by oneself and the world, and the different stories told by different individuals. The interaction is complicated, unpredictable, and endless. We insist, however, that both we and our students need to loop: this is the fundamental skill of thinking. The grist for scientific inquiry emerges from story-comparing; the products of science in turn become a part of the story-telling comparisons that fuel the humanities. The take-home messages here are two: Understanding is fundamentally not an individual but a social activity. And understanding has two sources: limited personal experience and comparisons of one's own stories with those told by others.

This is perhaps the most important thing we have learned from our College Seminar experience: Different styles need not be in conflict. We desire-perhaps ever more strongly, we need-to see binaries as mutually supportive and, if kept constantly in interaction with one another, mutually generative. Some students, like some faculty, are more comfortable with the "lateral," others with the "up-down" style; some with cultural stories, other with personal experiences; some with "humanities," others with "science"; some with performing, others with talking; some with women, others with men; and so on. But all have the capacity to deal with both poles of such binaries, and all need to appreciate the added strengths that doing so can bring.

Our classroom objective is not to promote one of these sorts of alternatives at the cost of the other, but rather to legitimize and strengthen both, to help those who naturally favor one to see the benefits of the other, and, most importantly, to experience how each contributes to and makes use of the other. To achieve the promise of this understanding requires the willingness of all faculty members not only to draw on our own preferences and expertise, but to explore enthusiastically the relevance of others' styles for ourselves, if for no other reason than to model for our students the activity in which we are asking them to engage.

We believe the lessons we have learned from our classroom experiences have a wider significance still. Human conflict continues to involve the creation of binaries and an associated belief that these represent conflicting stories, one of which must prevail at the cost of the other. At a time in history when the price of such conflict is measured in terms of the suffering of very large numbers of human beings, and potentially in the extinction of the human species, there may be no more important classroom task than to help students develop and appreciate an alternative perspective: that differing stories need not be oppositional, that they can instead much more advantageously be seen as the grist from which still better stories emerge. It is our task, as educators and citizens of the world, to work with our students to help them and ourselves develop the skills needed to continually create and recreate a human story from which no one feels estranged (Grobstein 2001a).

In gratitude to those colleagues who are quoted above, as well as to those who read and responded to earlier versions of this project: Jody Cohen, Ro. Finn, Diane Gibfried, Gail Hemmeter, Chelsea Phillips and Jan Trembley.

Works Cited

Abbott, Edwin. Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. 1885; rpt. New York: New American Library, 1984.

Belenky Mary Field et al. Women's Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice, and Mind. New York: Basic Books, 1986.

Berthoff, Ann E. "Is Teaching Still Possible? Writing, Meaning, and Higher Order Reasoning." College English 46,8 (December 1984): 743-55.

Bizzell, Patricia. "Cognition, Convention and Certainty: What We Need to Know About Writing." Academic Discourse and Critical Consciousness. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992. 75-104.

Brecht, Bertolt. Galileo. 1952; rpt. New York: Grove, 1966.

Burgmayer, Sharon. Understanding's Birth (2001): http://www.brynmawr.edu/Acads/Chem/sburgmay/understandingsbirth.html

Dalke, Anne. Teaching to Learn/Learning to Teach: Meditations on the Classroom. New York: Peter Lang, 2002.

----. The Grace of Revision, The Profit of "Unconscious Cerebration," or What Happened When Teaching the Canon Became Child's Play. Mss. in Circulation (2003): http://serendipstudio.org/sci_cult/bigbooks/spring03/grace.html

Dalke, Anne, Paul Grobstein and Elizabeth McCormack. Theorizing Interdisciplinarity: Metaphor and Metonymy, Synecdoche and Surprise. Mss. in circulation (2003): http://serendipstudio.org/local/scisoc/DalkeGrobsteinMcCormack. html

Damasio, Antonio. The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1991.

Dennett, Daniel. Consciousness Explained. Boston: Little, Brown, 1991.

Dewey, John. "My Pedagogical Creed." 1887; rpt. Philosophical Documents In Education. Edited by Ronald Reed and Tony Johnson. White Plains, New York: Longman, 1996.

Dubrow, Heather. "Thesis and Antithesis: Rewriting the Rules on Writing." The Chronicle Review (December 6, 2002): http://chronicle.com/weekly/v49/i15/15b01301.htm

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. "Nature." 1836; rpt. Essays and Lectures. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, 1983.

Flower, Linda and John Hayes. "A Cognitive Process Theory of Writing." College Composition and Communication 32, 4 (December 1981): 365-387.

Goldberger, Nancy Rule et. al, Editors. Knowledge, Difference, and Power: Essays Inspired by Women's Ways of Knowing. New York: Basic Books, 1996.

Grobstein, Paul. The Brain's Images: Co-Constructing Reality and the Self (2002): http://serendipstudio.org/bb/reflections/upa/UPApaper.html

----. Getting It Less Wrong The Brain's Way: Science, Pragmatism, and Multiplism (2001b): http://serendipstudio.org/~pgrobste/pragmatism.html

----. Science As "Getting It Less Wrong" (1993): http://serendipstudio.org/sci_cult/truth.html

----. September 11, 2001(2001a): http://serendipstudio.org/forum/newforum/11sept01-read.html

LeGuin, Ursula. The Left Hand of Darkness New York, Ace, 1969.

Lindemann, Erika. "What Do Teachers Need to Know About Cognition?" A Rhetoric for Writing Teachers. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. 87-107.

McDermott, Ray and Herve Vareene. "Culture as Disability." Anthropology and Education Quarterly 26,3 (1995): 324-348: http://serendipstudio.org/sci_cult/culturedisablity.html

Norretranders, Tor. The User Illusion: Cutting Consciousness Down to Size. Trans. Jonathan Sydenham. New York: Viking Penguin, 1998.

Philosophy of the Education Program. 2003. Bryn Mawr and Haverford Colleges. http://www.brynmawr.edu/education/philosophy.shtml

Polanyi, Michael. The Tacit Dimension. New York: Anchor, 1967.

Questions, Intuitions, Revisions: Telling and Re-telling Stories About Ourselves

in the World. College Seminar. Bryn Mawr College. (Fall 2001. Fall 2002):

http://serendipstudio.org/sci_cult/f01/

http://serendipstudio.org/sci_cult/f02/

Sacks, Oliver. "The Last Hippie" and "A Surgeon's Life." An Anthropologist on Mars. New York: Vintage, 1995. 42-107.

Sexton, Anne. Transformations. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1971.

Snow, C.P. The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution. Cambridge: University Press, 1959.

Stern, Janna. Measure for Measure: An Artistic Exploration of Eating Disorders, Body Image, and the Self (2003): http://serendipstudio.org/exhibitions/stern

The Two Cultures: A Conversation (2001): http://serendipstudio.org/local/scisoc/snow.html

Vygotsky, Lev Semenovich. Thought and Language. Trans. Eugenia Hanfmann and Gertrude Vakar. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press, 1962.

| General Science In Culture Forum

| Science in Culture

| Serendip Home |